Jean Sibelius once made a famously acerbic remark about his sparse Sixth Symphony: ‘Whereas most other modern composers are engaged in manufacturing cocktails of every hue and description, I offer the public pure cold water.’ In effect, Sibelius was only stating in starker terms a position he had already taken when Gustav Mahler met him in 1907 on a tour of Finland. To Mahler’s expansive Romantic notion that ‘the symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything’, Sibelius countered: ‘I admire the symphony’s style and severity of form, as well as the profound logic creating an inner connection among all of the motives.’ There is more than a hint of Sibelius’s inward-looking austerity and cohesion about William Scott’s achievement.

Often, Scott’s universe might be regarded as a kind of pictorial counterpart to that of the composer whose Fourth Symphony was dubbed the Barkbröd in reference to a nineteenth-century famine during which Scandinavians mixed ground-up birch bark with flour to survive. Read Ulster for Finland and one begins to get the flavour of the painter’s roots (born in Scotland, he spent his hard-bitten youth in Northern Ireland). Of course, this was not ultimately a question of economic deprivation alone, although Scott’s beginnings were humble enough and his hallmark empty pots, pans and lone mackerel on a plate hardly suggest Gordon Ramsay (in fact, the artist couldn’t even cook). Rather, it was more like a self-imposed aesthetic diet, a willed mortification of the spirit.

As Sibelius’s stance grew partly in reaction to the extravagances of atonalism and other Continental avant-garde developments, so Scott came to distance himself from European and American modernism per se, notwithstanding his well-documented personal ties to Mark Rothko and other contemporaries. The waters of the various harbours that he painted and the recurrent pale colours or grisaille are cool in more than literal temperature, chill in a sense closer to what Sibelius said he had offered the public instead of cocktails. Scott put the whole matter bluntly: ‘I was brought up in a grey world, an austere world: the garden I knew was a cemetery and we had no fine furniture. The objects I painted were the symbols of the life I knew best and the pictures which looked most like mine were painted on walls a thousand years ago.’ In short, he had a preference for the primitive.

William Scott

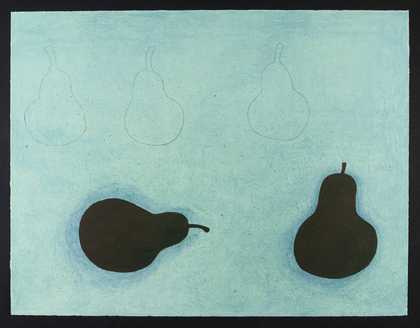

Pears (1979)

Tate

The preference for the primitive has been a recurrent trend in art and life since antiquity: E.H. Gombrich traced its fortunes in his last book of the same name published posthumously in 2002. Much in Scott’s vision fits the recurrent patterns of taste that Gombrich’s study uncovered. For example, Scott had a deep aversion (confirmed to me by his son James) towards a too-slick, virtuoso handling of paint and draughtsmanship – a tradition epitomised in Britain by, say, the brilliant touch of a William Nicholson – instead opting for blockish forms, coarse surfaces and an anxious line. This sentiment is as ancient as the Roman rhetoricians who, in Gombrich’s words, contrasted ‘the hard and angular shapes of archaic art to the supple grace of Hellenistic masterpieces’. Like Scott, they found a virtue and sincerity in plain speaking (carefully as it might have to be crafted). In turn, Scott said: ‘I find beauty in plainness.’ In his estimate, Ben Nicholson bettered William.

To be sure, Scott’s was not the loud variety of modernist primitivism familiar, for instance, from Picasso’s practice circa 1907 and Die Brücke, or even Dubuffet’s. It seems nearer to the quiet archaism of Gauguin, Moore or Matisse’s simplifications, albeit with faint traces of the post- war ‘geometry of fear’ look – not to mention ‘the plain sense of things’ espoused across the water in Wallace Stevens’s poetry. The apparent voids in Scott’s paintings – from the rectangular planes of his table tops and the quasi-abstractions of the 1950s to the pervasive chromatic fields during the 1970s – tend to feel as immanent as Rothko’s ‘emptiness’ or that in Stevens’s The Snow Man: ‘For the listener, who listens in the snow,/And, nothing himself, beholds/Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.’ Scant wonder, too, that in his final decade or so, Scott was drawn to the stripped-down art of ancient Egypt and its hieroglyphics. Again, a venerable precedent springs to hand. It was Cicero who warned about the double-edged delights of the overly sophisticated senses: ‘How much more brilliant, as a rule, in beauty and variety of colouring are new pictures compared to the old ones. But though they captivate us at first sight the pleasure does not last, while the very roughness and crudity of old paintings maintains their hold on us.’ The same applies to Scott’s idiosyncratic dour awkwardness. Whether it is his earlier seated nudes – their crudely spiky, reductive cast reminiscent of Lear’s exclamation, ‘Is man no more than this?… a poor, bare, forked animal’ – or the grainy, ramshackle images typified by White, Sand and Ochre 1960–1, his work tends to linger in the mind precisely because of its introversion and doggedness. To echo Sibelius on his melodic concision, all its visual motifs resemble the members of one extended family, as still life becomes landscape, figures turn into objects and back, and the little and the large fuse. Akin to a relative whom we half recognise, a latent propinquity haunts Scott’s compositions, prompting us to wonder about the impulse that alike drives them.

William Scott

White, Sand and Ochre (1960–1)

Tate

Before Scott pared his effects down with Occam’s razor, as it were, simplifying them into signs, one or two fledgling efforts give a clue as to what he would subsequently turn against – to borrow Gombrich’s phrase, the nature of his ‘avoidance reactions’. A little-known Still Life from 1935 depicts a lemon, apples, a pear or two, a white cloth and what must be a Bénédictine bottle. Surprisingly sophisticated in its painterly touch and evoking Chardin, this exercise hints at the route not taken, the sensuousness that underlay Scott’s later sobriety. Indeed, the multifarious pears and the occasional egg that he painted in the 1970s are about as edible as revenants, which is what they are: mental transformations of old empirical observations. To reach this rarefied state, he took to painting from photographs and from recollection.

Was the thing in itself, the French liqueur and the deft strokes of pigment (evident again in the Cézanne-influenced Girl at a Table (Figure and Still Life) of 1938 with its lush blue shadows playing against orange fruit), too seductive and, hence, distracting for the serious arena of two dimensions? If so, this was why Scott wanted a ‘time lapse’ between what he saw and how he painted it, “a waiting time” for the visual experience to become involved with all other experience. That is why I paint from memory’. It is this distance that separates Scott, even at his most exuberant in the late 1950s, from the lusty immediacy of American gesturalism and Abstract Expressionism in general, despite some superficial parallels. The exceptions to this rule are Philip Guston and Rothko. The former moved between representation and abstraction, immediacy and memory, in ways analogous to Scott, by the late 1940s submerging objects and anatomies into traces and schemata, then a decade or so later wrenching them back from a painterly morass. In Rothko’s case, Scott’s affinity with his American friend hinges less on a shared passion for colour or its lack – the large still lifes that erupt into lush golden and azure tonalities, alongside the monochrome, rectilinear figure abstractions that are his counterparts a decade beforehand to Rothko’s final ‘black and grey’ canvases – than on inner purpose. Namely, the urge that Rothko defined: ‘Tension: conflict or desire which in art is curbed at the very moment it occurs.’ In both artists, there is a case to be made for concluding that they were closet sensualists.

Little else explains the weird role of metamorphosis in Scott’s imagery, which derived not from Surrealism, but rather from the inherent mutability of psychic forces that are liable to be repressed or channelled so that they elude overt recognition. Here an admission by Scott about a picture he executed in 1948 spoke volumes: “It is probably one of the first instances when I make a double image… These objects now take on another meaning, which is obscure, and I don’t personally like to point it out.” A Freudian reading would seize on this statement and such instances as Scott’s erotic sketches for Private Suite 1973 with relish. Perhaps, though, his reticence is just as relevant. Following Rothko, he preferred ‘the simple expression of the complex thought’, as opposed to the blatant self-repression and dualism that the former had discerned in Mondrian: ‘A Calvinist who spent his life caressing canvas.’ Anticipating later artists such as Donald Judd and Agnes Martin, who walked a tightrope between severity and the senses – witness the rainbow hues that the former secreted within his boxes and the latter’s minimalist odes to joy – Scott’s art is a strangely memorable testimony to the ambiguous pleasures of puritanism in a disenchanted world.