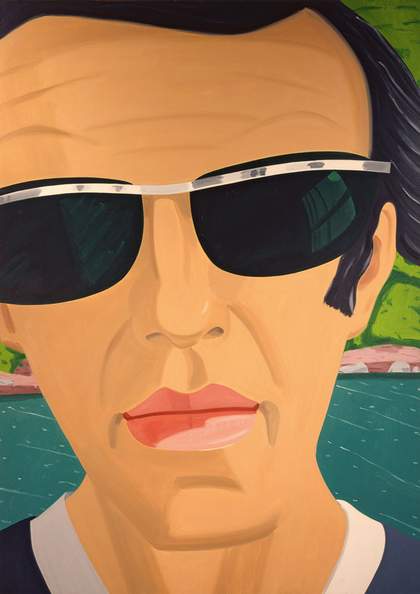

Alex Katz Self-Portrait with Sunglasses 1969

Oil on canvas

243.8 x 172.7cm

All Katz images © Alex Katz, DACS London/VAGA New York 2012

Courtesy Alex Katz Studio, New York

Martin Clark

How did you get started as an artist? Did you always want to be a painter?

Alex Katz

I grew up in St Albans, a suburb of Queens in New York which had emerged between the wars. My parents were Russian – my mother was an actress and my father a businessman. I always enjoyed doing art. It seemed like something that wasn’t in the immediate present. There were probably 40,000 people living there at that time, in these three-storey homes. There weren’t any churches, synagogues or a mall where people got together, so you really knew only the people on your block, and on my block there turned out to be two other artists, one of whom was an older guy called Dick Crockett. We did artwork together, though he was much more talented. He wanted to be a commercial artist, and at that time I thought that was what I wanted to do. He enrolled at Woodrow Wilson High School, a pretty low-level vocational school that specialised in art, and I followed him. My parents weren’t so happy about it. It was basically all about clothes and dancing, but we did art every day. When I arrived I saw these drawings based on antique portrait casts and realised that was what I really wanted to do. So I drew from the antique, five days a week, for three years. By the end, I was very proficient at drawing.

Martin Clark

Then you went to Manhattan, to the Cooper Union…

Alex Katz

Yes. It was Bauhaus influenced with a real edge in design that you didn’t get at other schools; very original. Then, in 1949, I got a summer scholarship to Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture in Maine, where I got really involved in painting, and in particular painting from life.

Alex Katz The Black Dress 1960

Oil on canvas

183 x 213 cm

All Katz images © Alex Katz, DACS London/VAGA New York 2012

Courtesy Alex Katz Studio

Martin Clark

What was it like being a student in New York at the time?

Alex Katz

Well, that was when Jackson Pollock hit, and New York changed completely, turning into a real international place. The jazz was fantastic. The dance was fantastic. The poetry was great. All these things were going on simultaneously, and everything was accessible, all just a block away from the art school.

Martin Clark

Did you see yourself and your work fitting in there, with the kind of painting being produced by Pollock and Barnett Newman?

Alex Katz

I knew Pollock’s work. He was already the man. Newman only surfaced in the art world later. Newman had an early show, which was a bomb, and then a little later he had a show at French & Company, after which he took over the styling for the 1960s. From the beginning, the whole idea of making something realistic and new seemed to be an enormous challenge. But I just knew that the Abstract Expressionist path was not my route. I instinctively didn’t like the rhetoric. I instinctively don’t like ‘macho’; I find it kind of fake. My father was a real he-man, not a fake macho – he’d dive off bridges, stuff like that. But I wasn’t a he-man. And in a way I think I had more ambition, because at that point, for me, it would have meant becoming a second-line AbEx painter, like Joan Mitchell, whose work is really good, but it’s not original, or intellectual for that matter.

Martin Clark

So you knew that the painting you were making was going against the grain of all that Abstract Expressionism stuff?

Alex Katz

Oh yeah. I knew what I had to do, but I had no idea whether it was any good. Some painters liked my work. William King bought about five of my early small paintings from my first show at the Roko Gallery in 1954. That was great, because he was an artist I admired. In fact, all of my early sales were to painters. They supported me and that gave me something. By the end of the 1950s some very bright people thought I was good too, and I said: I’m never going to have to apologise for making representational paintings again.

Martin Clark

People talk about your work in terms of style and surface, while Abstract Expressionism is often said to embrace a kind of existentialism and depth. It feels to me that, through the attention you pay to surface, you actually get a lot deeper; you achieve a huge amount of depth. As AbEx developed, the danger was that it would become, at worst, a pose or process that seemed to signify depth and psychological complexity, whereas it wasn’t always necessarily authentic. In your painting there is a really strong sense of authenticity, of truth.

Alex Katz

To me, the surface is where the whole thing is. It’s probably the major factor in my work. And it’s basically about taste. Taste is not something you are born with. You like some things instinctively and don’t like others, while with a lot of things, you say: ‘Well, I don’t know.’ And then it clarifies itself. The definitions of art and of painting are not fixed. They keep changing – even for me.

Martin Clark

For a lot of those painters style was almost a dirty word. But actually all of them had a really strong style, they just didn’t like to talk about their work in those terms.

Alex Katz

That’s right. They said style was bad. I think they meant ‘stylised’. But they were all highly styled. De Kooning said he’d paint in any style, but he doesn’t. He paints in a de Kooning style. I thought that was baloney, and I believe it comes out of this thing about starting with subject matter, and the subject matter turning into content, and the content is form. That was the story. There was no room for style.

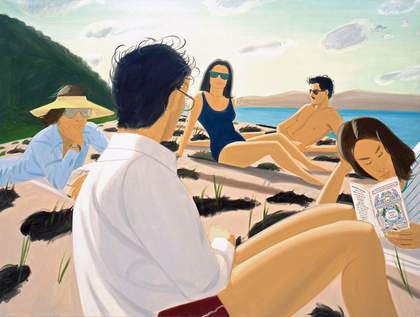

Alex Katz Round Hill 1977

Oil on canvas

180 x 243 cm

All Katz images © Alex Katz, DACS London/VAGA New York 2012

Courtesy Alex Katz Studio

Martin Clark

Your work not only has a very definite style – in terms of its technique, its composition, its attitude even – it also celebrates style through your subject matter, through your obvious interest in music and fashion. You seem to take style seriously.

Alex Katz

Yeah, I think style is the content of my painting, and style belongs to fashion. Fashion is in the immediate present, and that’s really what I am after in my work. I’ve always thought that music reaches the present, but painting doesn’t, and that’s what I wanted to do. I don’t think it can ever do it, but the wish is there.

Martin Clark

How did you arrive at your very reduced graphic language and the broad areas of colour and flattened form?

Alex Katz

I was thinking about Pollock again, this was in the mid-1950s, and I’d seen an Alberto Burri show and a Nicolas de Staël show, and I wanted to try to get my work to feel more concrete in a way. I remember I was painting a field, and I was trying to decide which one colour would give me the feeling of the field, and the time, and the light. It developed from there, so by the late 1950s I was starting to figure out this idea of the flat not being flat. In other words, that it had the right depth, the right weight, you know? And I was looking at Kline and Rothko for that.

Martin Clark

Throughout your career, you seem to return to the same kinds of subjects – portraits, landscapes, figure studies, seascapes, flowers. Despite a really strong sense of the contemporary moment in your work, they are quite classical subjects.

AK: The modernist notion is you have to work from the immediate past. I think that is very limiting, considering the cultural world we live in. As far as I’m concerned, I can work from anything I want to, from early Italian Renaissance paintings to advertising billboards.

Martin Clark

And do you approach the making of a portrait or a flower painting very differently?

Alex Katz

You work inside the form – from its traditional form. It started with compositions, right? So I said: ‘Well, let’s look at compositions.’ Then I realised there weren’t that many in twentieth-century art, they were more like arrangements, as in a Newman picture, or constructions, as in a Picasso or de Kooning painting, where they build up and then tear down the composition – except it’s not a composition. A composition has to be planned in advance to get all the pieces to move. So I found myself looking at Watteau, for instance, who is terrific at compositions and gestures, or Rembrandt, who also has great gestures – he has no taste, but he’s fantastic at gestures.

Martin Clark

You were finding this in European art, but was there anything in American art that was useful?

Alex Katz

Well, the idea of the big painting comes from looking at American art. It was a way of getting out of Paris, going to the big format…

Martin Clark

That’s interesting, because your paintings feel so American.

Alex Katz Ives Field 1956

Oil on canvas

98.4 x 99.5 cm

All Katz images © Alex Katz, DACS London/VAGA New York 2012

Courtesy Alex Katz Studio

Alex Katz

That’s what people say, but actually a lot of it comes from European painting. In New York we have great museums such as the Museum of Modern Art, which has a terrific collection of Picassos, Mirós and Matisses. I looked at them a lot. And then they had these travelling shows featuring European masterpieces. People didn’t travel as much then, so they wouldn’t have had the opportunity to see this work. And when you saw these really top paintings, you went for the highest standard. I don’t feel intimidated by old stuff. It’s more like being inspired.

Martin Clark

How do you make your paintings? Do you start with drawing?

Alex Katz

I generally start with oil sketches, because I can paint more quickly than I can draw. In this way I try to capture the sensation of what I’m doing, getting into the unconscious and creating the images, and then figuring out what I did. Sometimes I can make as many as seven sketches in order to get the light right. And then I’ll do a drawing of it, if I need to, to make the forms more accurate.

Martin Clark

Has that process changed over the years? Do you still work in the way you did 30 or 40 years ago?

Alex Katz

Yes and no. I did the early paintings on panels which had a gesso ground. I wanted a hard surface. When you put oil on gesso it dries quickly, and you can put paint over paint and drag it through the paint. I didn’t want that soft surface of canvas. I didn’t want the scrubbing look, or the layered look of, say, a Braque painting, where you see the paint on top of paint. I wanted it be really direct. By the end of the 1950s I decided I wanted to do bigger works. I switched to canvas using a lean ground, like gesso, but it was brittle, so I used a fatter ground and a fatter medium. What bothers me about the early twentieth-century painters is that they all wanted the paint to look fresh, so they painted with turps and had open, porous surfaces. I wanted a closed surface, so I used thinner paint on a fat ground. It takes about three months to set, but then it’s really hard. You don’t have to varnish it. By the end of the 1960s I had the technique down cold.

Martin Clark

Do you work from photographs or with models?

Alex Katz Walking on the Beach 2002

Oil on canvas

243.8 x 487.7cm

All Katz images © Alex Katz, DACS London/VAGA New York 2012

Courtesy Alex Katz Studio

Alex Katz

My work is done largely from life. I used other people’s photographs for the nostalgia in them in the 1950s, but I stopped painting from them by the late 1950s. I occasionally use them for inspiration, and then I get people to pose based on the photos. I did take photographs for a series I did at the beach in Maine in the early 2000s, as in the painting Walking on the Beach 2002. We used to go to the beach every afternoon and have a cup of coffee, sit on a bench and look, and I observed gestures in people on the beach that you could never get twice. So I started taking a lot of shots there. I got some interesting pieces – some of those seascapes with old people. They were developed partially from photos. I finally got one I really liked and that was the end of it. The next time it didn’t work. I never used the camera again.

Martin Clark

I’m glad you mentioned the beach paintings, because a lot of people think of you as a quintessentially New York painter, but you’ve been going up to Lincolnville in Maine every summer for more than 50 years now. It’s an aspect of your work that we are focusing on in particular for the shows at Tate St. Ives and Turner Contemporary.

Alex Katz

We’ve been going up there since we bought a house in the 1950s. And I paint there. It’s very different from New York. I spend more time outdoors.

Martin Clark

As well as the exhibition of your own work at Tate St. Ives and Turner Contemporary, you have selected a display from the Tate collection. Could you talk about some of the artists you have chosen?

Walter Sickert The Front at Hove (Turpe Senex Miles Turpe Senilis Amor) 1930

Oil on canvas

63.5 x 72.6 cm

© Tate

Photograph © Tate Photography

Alex Katz

I mostly chose work that I would like to look at. It wasn’t a matter of selecting the best painting by that artist. There is quite a lot of nineteenth and early twentieth-century European painting. I’ve always liked the works of both Walter Sickert and William Nicholson. To me, they are similar. They’re highly civilised, but very good provincial painters. I’ve also got a Stubbs in there. I admire the sense of scale in his pictures – and of course he was great at painting horses. I’ve chosen a painting of a vase of flowers by Rousseau, one of my all-time favourite painters. For years, a book on Rousseau was the only art book I owned. I am also thrilled to be able to include two Chaim Soutine paintings from the 1920s. They feel very contemporary. I don’t know what it is about them I like… I think it’s the vision he had and the way he painted. He just had a lot of pizzazz. De Kooning preferred Soutine to Van Gogh. His brushstrokes are never dull. It’s dazzling how one brushstroke sits next to another.

Martin Clark

You also have a Hockney. You were associated with Pop art in the 1960s, when he first started getting attention. Did you meet him?

Alex Katz

I’ve met him a couple of times, but I’m pre-Pop. I mean the Pop artists, a bunch of them came round to my work. But I always admired Hockney’s sense of self, you know? I thought it was kind of terrific. And I always liked his public graciousness, which I thought was a really good example for artists.

Martin Clark

What are you working on now?

Alex Katz

I have been working on large paintings of roses, based on real flowers that I buy on the street corner. I keep upping the ante, so I did this brown one, which was a big risk, and it’s kind of fun to take risks. It’s really scary. And I’ve been trying to paint a 20 foot wide white-on-white roses picture. I’m trying to get the white to the background, but when you have the strong leaves the roses become recessive, and if you lighten the leaves, the whole thing is going to look like a weak Impressionist painting. I made some drawings afterwards – you have to figure out the balance as you go along.

Martin Clark

Do you paint the final works in one hit?

Alex Katz

They’re all done in one day.

Martin Clark|

So it’s physically quite demanding, but I guess you’ve worked through a lot of processes to get to that point?

Alex Katz

A lot of processes. The paints are all mixed, the drawing is on the canvas and I put all the brushes out, so it’s a matter of just putting the paint on the canvas. I use a cartoon and then I put the drawing on, and then when I paint it, I leave out a lot of the description. So we go into no-man’s land. You’re dealing with stuff that’s not descriptive; basically, a lot of it is just instinctive.

Martin Clark

Are you making paintings every day?

Alex Katz

Yeah. I’m painting as much as I ever did, and my painting is better. I’m sort of restless, I guess. As the choreographer Paul Taylor said: ‘The one thing you don’t want to do is bore yourself in the studio.’ I think most painters just repeat what they have been doing. Some days you don’t get it right. Like in that rose painting? Everything was wrong, but I just muscled my way through it. If you have the right brush and the right paint and the right surface, then everything can be really wonderful.