Edvard Munch was born four years after Darwin published his theory of evolution. As the 1860s progressed and science elbowed out religion, scientists assumed priestly authority and the camera became the instrument of scientific record. How to paint in a post-photographic age? Norwegian artists of the day took refuge in Naturalism, made use of the cameras obscura and lucida and capitalised on still having the monopoly on colour. In 1879 fifteen-year-old Munch went on his first summer sketching tour, taking with him a camera lucida to help him to frame reality and transfer it accurately to paper. In the evenings he operated the magic lantern slides for Pastor Storjohann, who was introducing spiritualism to Norway. Science might have killed God, but the moral blank left by His death was leading to a rise in occult and pseudo-scientific alternatives.

Munch’s favourite sister Sophie died when he was fourteen. By 1885 he was a leading young Naturalist painter and felt ready to attempt the subject of her death, but Naturalism, and Impressionism, which he had seen in France the previous year, proved too objective to express the emotional turmoil of the event. Frustrated, he attacked the canvas with the handle of the brush: we can still see the marks. Throughout the year that he was painting, scrubbing out and repainting The Sick Child (1885–86; a later version, dated 1907, is in the Tate collection), spiritualism was sweeping Norway. Mediums moaned, ectoplasm oozed, a magazine was started and opposite Munch’s studio a spiritualist ‘scientific library’ opened, where you could study photographs of the dear departed blurrily coexisting with the living in a fourth dimension invisible to the human eye, but apparently visible to the camera.

Munch was never interested in spiritualism as a credo – indeed, at an Ouija board session with August Strindberg, he nearly severed their friendship forever by jokily spelling out M-E-R-D-E. However, he was fascinated by how spiritualist photographs, with their apparent synthesis of the material and the immaterial, assuaged the public’s hunger for a return to the spiritual and the sacred that mere Naturalist depiction ignored. Weeping, he dripped thinned paint down the canvas like his tears. Spraying fluid colours directly on to the surface, he achieved unfocused ‘ectoplasmic’ blurring round the central image, which gave a mystical weight to the composition that was further deepened by the unearthly light source apparently emanating from the dying girl’s head. Munch called it his first ‘soul painting’, and posterity called it Expressionism.

By Munch’s time there were several ways of producing spirit photographs: by waving something across the lens during exposure, by using a pre-prepared plate that had an image on it already, or simply by double exposure – one photograph taken on top of another, without winding on the film between. Spirit photography brings together within the same frame two images that have neither a common vanishing point nor a common light source. They thus offer a pictorial model that breaks the fundamental conventions of Western painting. This was to be of great importance in Munch’s art, rendering it peculiarly modern and original, as in Women in the Bath 1917.

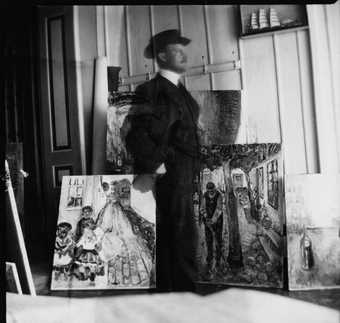

In 1902 he acquired his first camera, a small Kodak with an automatic release, which he kept until 1910, using it to experiment with spatial perception. A major theme emerged: the artist and his art. At first, he placed the camera on a table and used the automatic release, but soon, without realising that it was one of the spirit photographers’ techniques, he passed a white sheet of paper across the lens during exposure to etherealise the light source, conferring a spectral quality that emphasises the loneliness of these self-portraits. Next, wanting to merge himself completely with his artwork, he took double exposures. This was an extremely radical technique outside hoax photography until the 1920s. He photographed his art and then, without winding on the film, took the self-portrait, so that in the final image art and artist fuse in a single work.

The same year that Munch bought his Kodak, Carl Paul Goerz produced the first successful wide-angle lens, the Hypergon-Doppel-Anastigmat. It gave a clear 135-degree picture and was developed for architectural photography, but close-ups of the human face resulted in novel, almost fish-eye distortions. Examples of these were published regularly in the photographic magazines the artist was reading while getting to grips with his new camera. Munch experimented, taking arm’s length self-portraits that produced similar distortions: foreshortening, exaggerated perspective and interesting areas of deliberate indistinction, features he adopted in paintings such as Galloping Horse 1910–12, On the Operating Table 1902–03, Red Virginia Creeper 1898–1900, Fresh Snow in the Avenue 1906 and the Green Room series 1907, whose wide-angle treatment of perspective greatly increases the threat and claustrophobia of the closed room.

Edvard Munch Self Portrait at 53 Am Strom in Warnemünde 1907

Gelatin silver print

9 x 9.4 cm

© Munch Museum/ Munch-Ellingsend Group/ DACS 2012

Courtesy Munch Museum Oslo

In 1907, while the artist was fulfilling a commission to paint a posthumous portrait of Nietzsche, he was visited by the philosopher Eberhard Grisebach. They talked of determinism and the duality of man, a subject of particular interest to Munch, who had an acute awareness of the simultaneity of objectivity and subjectivity – walking beside himself, as he put it. Both men loved Goethe’s Faust and they discussed the idea that Faust and Mephistopheles were not two people, but the two sides of one. From now on the alter ego enters Munch’s iconography, and he periodically makes pictures in which light and dark male figures represent two sides of the same person: The Fight 1932 and The Splitting of Faust 1932. During the same summer that he was thinking about these things, he employed two sisters as models, Olga and Rosa Meissner, whom he painted again and again in the series Weeping Woman 1907. He photographed Rosa in the same pose as the painting, nude with drooping head. And, in the nearest he ever gets to a hoax spiritualist photograph, he probably directed Olga, clothed in pale lace, to move in and out of the frame during the exposure so as to leave a ‘spirit image’ behind on the left. The physical similarity between the sisters also conjures the doppelgänger.

Invited to exhibit in Berlin in 1892, Munch found the avant-garde fascinated by occult and supernatural wonders. He was loaned a book of photographs of auras, a kind of flaming corona apparently surrounding all living beings, though visible only to the occult lens or eye. Iconographically, the aura is an interesting update of the halo in a post-Christian world: it makes the subject the centre of a force field that hugely increases expressive impact. He immediately incorporated directional aura lines in Self-Portrait with Cigarette 1895, Madonna 1894–95 and Dagny Juel 1893, while using them to great effect in The Scream 1893.

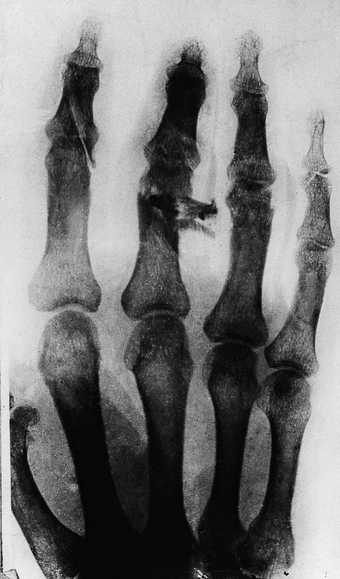

X-ray of Edvard Munch's left hand before surgery at the Rikshospitalet, showing a small bullet from a revolver in the shattered middle finger (1902)

© Munch Museum/ Munch-Ellingsend Group/ DACS 2012

Courtesy Munch Museum, Oslo

No sooner had he learned about auras than X-rays were discovered. Munch was in Paris, where the new development was treated as cabaret. People gave X-ray parties in which the room glowed blue-ish, glass and jewels became incandescent and actors performed a skeleton dance. There was a craze for X-ray portraits taken through blocks of wood; the resulting images conveying two simultaneous realities had much in common with spiritualist photographs, except they were not ghosted by ectoplasm, but by the pattern of woodgrain and knots. This new twist on making visible the invisible appealed to Munch, who typically reversed the concept in his woodcut prints by using unprimed woodblocks and leaving the knots and striations to become part of the finished picture. He had already portrayed the human form as part skeleton and part living flesh in Death and the Maiden 1893 and The Scream before Wilhelm Roentgen published his first X-ray, showing the skeleton of his wife’s arm. Shortly after, Munch made his first lithograph, Self-portrait with Skeleton Arm 1895: part portrait, part X-ray and part prophecy, one seen to be fulfilled when we look at the 1902 hospital X-ray of Munch’s arm with a bullet lodged in a finger bone as a result of an accidental shooting during a lovers’ quarrel.

Later, as an older man looking back on how threatened he had felt as an artist during a period so fascinated by the objective gaze of science, Munch concluded laconically: ‘The camera can never compete with brush and palette – so long as it cannot be used in Heaven or Hell.’ It was his genius to recognise and exploit contemporary thought and technology that would help him to take his art to exactly those places.