Does London have an image problem? Do we know how it really looks? When visitors arrive in Paris, noted Roland Barthes, the first thing they do is look for Paris, and they know where to go. While that city has been reminding the world of its official image at least since Baron Haussmann remodelled its centre, London eludes easy definition. Culturally and architecturally, it is too varied. Look how politicians and PR companies struggle to brand it in the run-up to the Olympic Games (even the Olympic logo tries to make a virtue of incoherence). The capital’s image is like its layout: an ad hoc weave of unexpected encounter and quiet revelation.

In 1958 Walker Evans, the quintessentially American photographer with a soft spot for England, published a photo-essay titled The London Look. Strolling from Stratford in the east to Ladbroke Grove in the west, he noticed doorbells, quiet corners, fences and stonework. Avoiding the guidebook clichés, he was after the ‘subtler quarry’ of things hidden in plain view. Evans the flâneur revelled in the overlooked. No Londoner would photograph that particular configuration of half-plastered brick, drainpipe and railing, but they may smile at how typical it remains. On a Sunday morning he rose early to visit a deserted street in Paddington. ‘A perfect scene for a rousing manhunt, or at the very least, a pleasantly sordid, heartbreaking tryst,’ reads his caption.

Around the same time the French director Alain Resnais was scouring the city for locations for a film based on the adventures of Harry Dickson, the fictional London detective. It was to star Laurence Olivier, but was never made. All that remains is Repérages 1974, the book of Resnais’ enigmatic, haunted photos. The dank and creepy pedestrian tunnel under the Thames at Greenwich. The premises of Braithwaite & Dean, a barge company at Rotherhithe. Back alleyways, bomb-damaged streets and post-war housing. Like Evans, Resnais saw a deserted city poised in anticipation. These are photorealist backdrops awaiting the daily drama.

Another London: International Photographs 1930–1980 offers up the missing comédie humaine. In pictures by dozens of photographers from overseas, Londoners seem to perform their citizenship like extras in a teeming production. The American Eve Arnold composes a young woman in a flat-share bathtub like a publicity still for a 1950s melodrama. The Swiss Robert Frank shows Stock Exchange bankers gliding in endless rehearsal through a very English fog, as if the war had not disrupted a thing. (Perhaps ‘endless rehearsal’ is what we prefer to call ritual). The Chilean Sergio Larrain tilts his camera at pedestrians to snatch a frame reminiscent of free-form documentary film. In each of these images Londoners appear to be enacting as much as being themselves.

Photography appeals because it escapes narrative and wrongfoots the easy explanations it can seduce us into making. Like the visitor with fresh eyes, the camera takes in everything. It sees without hierarchy or intention, with no knowledge of the before or after. In fact, it sees more than any human can, recording surfaces and objects with unimaginable realism. Its voracity and its veracity are inseparable.

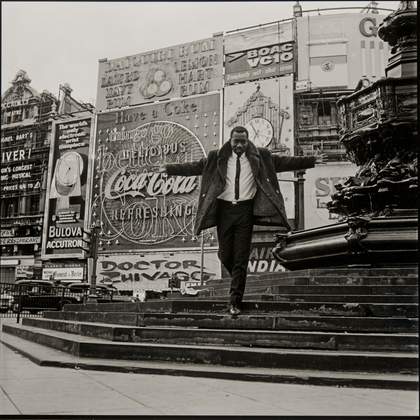

James Barnor Mike Eghan at Piccadilly Circus, London (1967)

© James Barnor / Autograph ABP

In the final print the smallest things may become insistent signs, calling inexplicable attention to themselves across time. Are the gleaming tram tracks and worn cobblestones in René Groebli’s 1949 shot of Westminster Bridge still there, beneath the tarmac surface? The pearly king’s outfit photographed by Dorothy Bohm in 1960 is still a familiar sight, but this leaves the rest of her shot of a crowded Petticoat Lane market to become a feast of sartorial incident. Marc Riboud could not resist the touching comedy of an elderly woman somehow resembling the bus stop at which she waits, but every square inch of that picture is now rich evidence. Not just her clothes and shoes, but her slight body and facial physiognomy. Was she typical or untypical? The photograph cannot say. Even her background may catch our contemporary attention with its unforced record of that patch of St. James’s in 1954.

This capacity for unpredictable significance is what troubles photography’s artistic ambitions. All photos, indeed all films, end up documents, no matter what the makers’ intentions. And the value of that documentation cannot be known in advance. Who is to say which detail from which image may prick our personal memory, or cause us to re-evaluate our shared history? For audiences this is what makes historical photographs so fascinating, but for photographers themselves it is a humbling phenomenon, better embraced than resisted or resented.

This is why the period covered by Another London is remarkable. By the late 1920s cameras were light enough and negative film sensitive enough to be attuned to the fleeting impressions that came to define modern city life. As the sociologist and film critic Siegfried Kracauer put it in 1927:

The street in the extended sense of the word is not only the arena of fleeting impressions and chance encounters, but a place where the flow of life is bound to assert itself […] The kaleidoscopic sights mingle with unidentified shapes and fragmentary visual complexes and cancel each other out, thereby preventing the onlooker from following up any of the innumerable suggestions they offer. What appeals to him are not so much sharp contoured individuals engaged in this or that definable pursuit as loose throngs of sketchy, completely indeterminate figures. Each has a story, yet the story is not given.

In this milieu the photographic act was a matter of selection, framing and timing – the formal organisation of the chaotic stuff of the world for which the photographer was not entirely responsible. Eventually, of course, the observer affects the observed. By the 1980s citizens and their cities had become so saturated with pictures and so anxiously image-conscious that the relation between surface and deeper meaning became fraught, threatening to become indecipherable. This was the postmodernisation of daily life. As the philosopher Slavoj Zizek noted, how can we read appearances when denim is worn both by bankers and construction workers, and the whole population appears to shop at Gap? What happens when locality is smothered by architecture and commodities increasingly designed by the same globalised software, following the same committee criteria? Or when the same corporate branding is found in every high street? The subtleties that make life worth living become invisible.

It is no coincidence that the 1980s was when photography really began its ascendancy as self-conscious art, and it did so by embracing artifice and undermining the documentary presumption that the surface of the world carried significant information about its meaning. But just as we are tiring of the airless look and feel of parts of our cities, so audiences have begun to tire of the airless art with which it was complicit. The recent renaissance of street photography is a sign of this. The tentative return to photographing on the hoof and from the hip, trying to pinpoint the minor epiphanies and major shifts in city life, is a sign of resistance: a wish to drive a wedge into the cracks of corporatism and let the world breathe. But in our era of CCTV and the attendant suspicion of all cameras, street photographers are struggling to recover the easy naturalism of the genre’s great exponents, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bruce Davidson, Bill Brandt and others on view in Another London. These are historic images for sure, brimming with information about the past, but they would be mere nostalgia if they did not also have a resonance for us in the here and now.