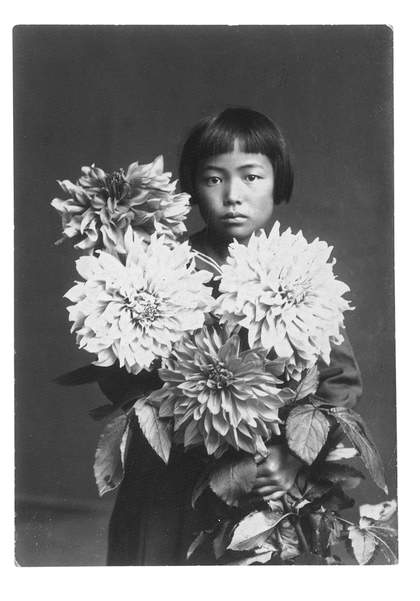

Yayoi Kusama at the age of ten in 1939

© YAYOI KUSAMA

Damien Hirst:

Do you feel that your work is optimistic?Yayoi Kusama:

No, I don’t feel my work is optimistic. Each piece of work is a condensation of my life.

This is the opening salvo in a short conversation first published in the catalogue for a solo exhibition by Yayoi Kusama at Robert Miller Gallery in New York in 1998. It provides a telling encapsulation of the work of a legendary figure in the art of the past half century, as the artist wishes that work to be construed. Kusama’s remarks on this, and on many other occasions, insist on, rather than merely validate, a reading of her oeuvre in biographical terms.

A flower field in the Nakatsutaya seed nursery owned by Yayoi Kusama’s family in Matsumoto, Japan

© YAYOI KUSAMA

The lineaments of her life, as she has recounted it, are as dramatic as they are well-rehearsed. Born in rural Japan in 1929 into a well-off family; had an unhappy relationship with an abusive mother; has continually experienced hallucinations since childhood and been prone to morbid obsessions; received a traditional training in Japanese nihonga painting while also being exposed to European modernism; left Japan for New York in 1958, where she was highly active and visible, but returned to her homeland in 1973 on account of ill health; remains in Tokyo today, as tirelessly productive as ever, but living by choice in a mental hospital.

The mature works for which Kusama is best known are all structured according to a compositional principle of febrile proliferation: the ‘all-over’ Infinity Net paintings, since the late 1950s; the stuffed-fabric sculptural agglomerations of phallic forms begun in the early 1960s; the dizzyingly recessive Mirror Rooms; the viral polka-dots with which she has, as she once put it, ‘obliterated cats, dogs, a horse, rocks, lakes, mountains, New York City and the Statue of Liberty’; even the unbridled flow of her writings. As early as 1964 she described one of her sculptural aggregations as ‘a logical development of everything I have done since I was a child. It arises from a deep, driving compulsion to realise in visible form the repetitive image inside of me’.

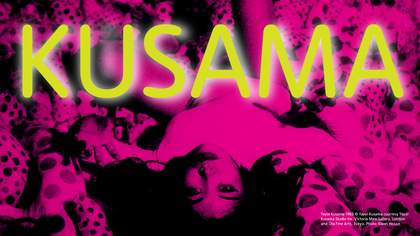

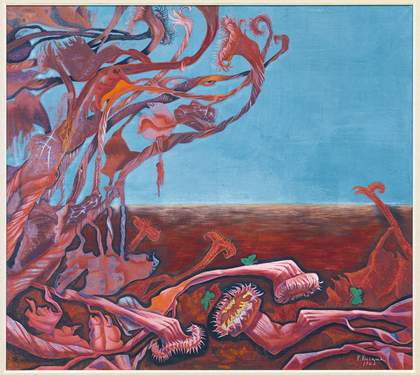

Yayoi Kusama

Lingering Dream 1949

Pigment on paper

13.7 x 15.2 cm

© YAYOI KUSAMA

In the light of such persistent assertions, it is not surprising that previous commentators have found confirmation of a life-long continuity of concerns in the scant but fascinating evidence of works from her student days and earlier. Lingering Dream 1949, for instance, is one of the few nihonga pieces from Kusama’s student days that she chose to preserve rather than destroy. Executed in mineral pigments on paper, this image derives from the memory of a seed-harvesting field that formed part of a nursery owned by her family in the town of Matsumoto, where she grew up. The nightmarish depiction of crimson sunflowers in a state of convulsive decay, among which a few green butterflies flutter about, bears comparison with the dreamscapes of European Surrealism, though Kusama claims to have been unaware of such precedents at the time.

From Lingering Dream we might follow a strain through her mature work right up to the giant polka-dotted pumpkins and writhing psychedelic flora of the more recent sculptures and installations, which is to say the proliferating images of various organic materials: seeds, flowers, fruit, leaves and plants, as well as sundry unidentified micro-organisms. This pervasive imagery invades the most abstract reaches of Kusama’s work, as we can see from a later painting such as the three-panel Weeds 1996. Even the accumulations of phallic forms are as redolent of the pistils and stamens of plant reproduction as they are of human sexual organs, which Kusama evidently found at once fascinating and frightening. Her profusions of flowers during the 1960s chimed with the times, of course, yet it is worth noting that the sculpture Flower Overcoat 1964, for example, was produced a year before Allen Ginsberg first advocated flower power as an instrument of mass anti-war protest, heralding a movement with which Kusama would become passionately engaged.

Yayoi Kusama modelling her Kusama Fashions in New York 1968

Photo: C Kosof

© YAYOI KUSAMA

Yayoi Kusama lying on the base of My Flower Bed 1962 in New York, c.1965

© YAYOI KUSAMA

Photo by Peter Moore

There exist two remarkably prescient drawings, dated c.1939, when Kusama was just ten years old, in which the central motifs – the inclined head and shoulders of a woman with closed eyes, in one case, and a vase of flowers, in the other – are overlaid by flurries of tiny spots and, in the latter instance, an array of radiating web-like, or flower-like forms that seem to float indeterminately between background and foreground.

An equally prescient photographic portrait, taken around the same time, shows a young Kusama all but subsumed into an arrangement of flowers, whose enormous blooms both echo and overwhelm the outline of her impassive countenance. This image is an uncanny harbinger of the later work, whose exploding patterns of biomorphic forms she has ascribed to a general condition of hallucinosis in an anecdote of which there are several variants: ‘One day, when I was a little girl, I found myself trembling, all over my body, with fear, amid flowers incarnate, which had appeared all of a sudden. I was surrounded by several hundreds of violets in a flower garden. The violets, with uncanny expressions, were chatting among themselves just like human beings.’

Yayoi Kusama

Awakening of Love 2010

Acrylic on canvas

130.3 × 162 cm

© YAYOI KUSAMA

Psychoanalyst Juliet Mitchell has observed of the self-annihilating aspect of Kusama’s art that ‘to become a beautiful flower instead of a miserable child involves psychically eradicating the child’. (The telling title of a work from 2000 is I’m Here, but Nothing.) That said, it seems that some of Kusama’s peers found it difficult to square the assiduous networking of her New York days, and her overweening desire for recognition, with such self-effacing credos as: ‘Obliterate your personality. Become part of your environment. Forget yourself.’ Today, however, the contrast between a life devoted to the cultivation of a consistent artistic persona, on the one hand, and a body of work in which subjectivity is in a constant state of dissolution into a swarming multiplicity, on the other, may be easier to accommodate. Kusama has stated that ‘painting pictures has been therapy for me to overcome my illness’. Her work also anticipates, however, a powerful current in recent philosophy in which all kinds of objects, animate and inanimate, may be reconsidered as potential bearers of partial subjectivity. Subjects for such speculative thinking have included ancient animistic rituals, neurotic phenomena and aesthetic objects, all of which are surely pertinent to the life’s work of Yayoi Kusama and its persistent diffusions of artistic personality into a superabundance of organic forms.