When I was a teenager I started to go to see contemporary art systematically and had a desire to meet artists. Among the first were Fischli & Weiss, who recommended that I visit Alighiero e Boetti. I had just turned eighteen in 1986 and was on a school trip to Rome, where he was living. I called him and he invited me over to his studio. He was extraordinarily generous with his time and spent an entire day with me, immediately introducing me to so many people, including his astrologer, Marie Angela. she was also Fellini’s astrologer, and she told me: ‘You will work a lot in Asia.’

From the beginning, I felt that Boetti, although very different from his American counterpart, was the European Warhol – you came into his orbit when you met him, which would change you forever. and that’s what happened to me.

That day was one of the most important days in my life. It became a blueprint for the things I could do. On the night train back to Zurich, I realised what I wanted to do with my career. If you spoke to other people who met him when they were very young, they would tell you that they experienced this epiphany. I became addicted to his energy, and whenever I could, I went back to Rome.

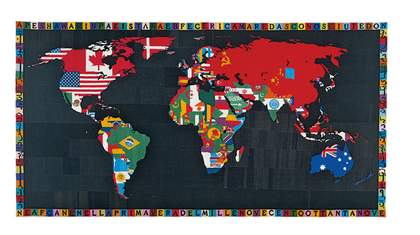

Boetti told me on that first encounter that in our time the art world would become much more of a polyphony of centres. It would go beyond Western art. He made me understand that globalisation would change the art world forever; yet at the same time we had a responsibility not just to embrace it, but to work with globalisation in the way that it produces difference by resisting homogenisation. You can see this idea in his maps. He said: ‘You should go to Asia and India,’ which I eventually did.

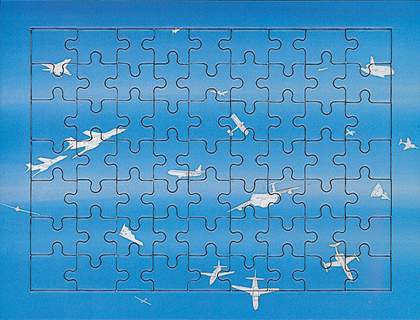

Boetti told me he was bored by the art world, because he was always being invited to do the same kind of project. The narrow boundaries made him feel claustrophobic. He had a long list of unrealised projects, and said it would be interesting to look at these and make them happen. What was his favourite unrealised project? He wanted to do an exhibition of jigsaw puzzles of all the aeroplanes of the world – a truly planetary exhibition. It took us five years, but by 1991, with the Museum in Progress, we started to do these small jigsaw puzzles to be distributed all over the world on Austrian Airlines planes. The second project (which remains unrealised) centred around his idea of how one could use the fax. He called it an ‘agency of fax’ (agenzia fax). Operating on a daily basis, people would subscribe and receive a fax every day. Like a daily newspaper: the Boetti newspaper. He liked to combine old and new media. He used stencils and water marks, and newspapers a lot – he copied them and gave them a new kind of aura. But he was also very aware of the changing media, and for him, at the time, the fax was new.

Alighiero Boetti

Jigsaw from a series produced in 1994 for Austrian Airlines based on one of Boetti’s works, Cieli ad alta quota (High skies) 1993

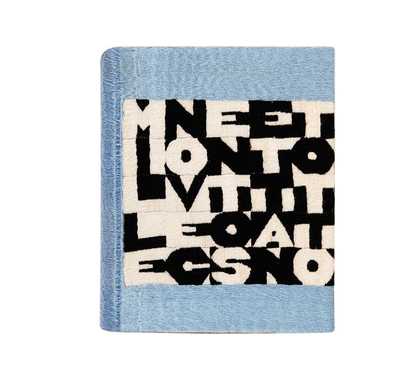

He also taught me that books are a very important medium for artists. I think his Classifying: The Thousand Longest Rivers in the World is one of the greatest artist’s books of all time. a very beautifully produced cloth-bound volume, it is about the impossibility of making a portrait of the rivers of the world. Each page features a particular waterway, in order of its length according to the most reliable source. This measurement is shown at the top of the page. But at the bottom you have all the alternative lengths, because obviously a river, given its meandering, can never be measured absolutely accurately. so there are all the different lengths for the nile, etc. There is order and disorder to the book, which is very much a Boetti idea. I think there is something Oulipian (à la Georges Perec, Jacques Roubaud or Raymond Queneau) about the work in its exploration of systems of order and disorder.

Alighiero e Boetti

Classifying: The Thousand Longest Rivers in the World 1977

Embroidered book cover

Boetti was a very literary man, referencing not only contemporary writers, but also those from antiquity. He was full of history and full of layers. Édouard Glissant was important to him, and the Martinican writer, poet and literary critic’s thoughts on an archipelago type of mapping and ‘creolisation’ can be found early on in Boetti’s work, in particular in his Mappa (Map) series, but also in his drawings and sculptures. The artist often talked about the homogenising forces in space – he wanted to find other spaces for art – and in time. (The first days I had with him in Rome were an incredible liberation, because I saw that a day could suddenly be like a week. It was a liberation from a standardised way of using time.) The time dimension is in all his work – from the beautiful clocks he designed down to the Lampada Annuale (Annual Lamp) 1966, one of my favourite pieces, which is a lamp that illuminates only once a year. I think hardly anybody has ever seen it light up.

Boetti’s inspiration was behind several shows that I curated, the first of which was an exhibition called Hotel Carlton Palace, Chambre 763. It was the 80th anniversary in 1993 of the 1913 Armoury show. There were about 60 or 70 artists exhibiting in my hotel room. Boetti’s contribution was a postcard we produced of his One Hotel in Kabul, an actual hotel he had owned, and which was obviously now long gone in war-torn Afghanistan.

Our Do It book was an instruction manual written by 168 artists and writers on how to make a work of someone else’s art yourself. Christian Boltanski, Bertrand Lavier and I wanted to do something that would show how art could travel in a different way, not through objects, but recipes and instructions. Boetti and I had talked a lot about that. He saw that there were all these other possibilities. When we published, it was translated into nine languages. It became like a musical score– it could be played in all of these different places. It was following Boetti’s vision of having something which could enter a dialogue with other cultures. now we have an art world which is polyphonic, with very dynamic art centres on all continents. Boetti’s idea with the One Hotel and using villagers in Afghanistan and Pakistan to make the embroidered maps was defining what Glissant called a mondialité, a difference-enhancing global dialogue to make the art world less Western-centric. It was kind of an obsession of his, and he travelled relentlessly to the east. That’s why it was very important that he was in ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Grande Halle at the Parc de la Villette in 1989. I will never forget that opening. Boetti was there with fellow artists Huang Yong Ping, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré and many others.

His spirit was a generous one: about the artist as a planetary citizen, rather than an artist in a bubble. He wanted to change the world. He had this extraordinary energy. It was impossible just to hang out with him, there was immediately always a call for action. He was super-stimulating. and he introduced this sense of urgency into my life. He kept telling me on that first day: ‘don’t become a boring curator.’ He kept making fun of my swiss slowness, saying: ‘The Swiss are so slow!’ Indeed, I still have this postcard he sent me: ‘dear Hans, velocity quasi zero’. When you grow up in Switzerland, urgency is not necessarily something you are confronted with. Mine was a rather quiet childhood in the countryside, near a lake. I think ‘urgent’ is a word I always associate with him. It’s also interesting when you look at his letters: they inevitably express energy flowing in all directions. That incredible appetite Boetti had for the world was a huge inspiration – it attracted me because I’ve always felt this drive for his sense of the encyclopaedic. In Tutto (Everything), another great series of work, he tried to gather together everything; he had that urge like a child. Inspired by him, I did a book with Guy Tortosa about unrealised projects. We invited Boetti to tell us about his unrealised projects. One was his design for an agricultural monument – a tree on an infinite column of earth; a homage to the tree.

It was tragic that Boetti died so young. When I visited him for the last time he was very ill. I have this very strong memory of being in his flat and there in a corner was one his works – a map with a totally black sea. It was the map of death.