Here are three Yayoi Kusama portraits, ranging over the seven decades of her working life: The first, Untitled 1939, is a drawing of her mother and one of her earliest extant works. In it a girl in a kimono, her face between pensive and sad, has her eyes closed. Between us and her there’s a curtain of snow, or ash, like a prophecy of fallout, which gathers and adheres when it comes to the vulnerable places on her face, eyelids, neck.

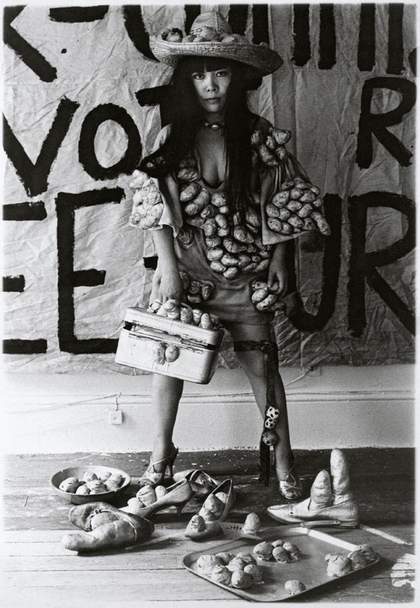

The second is a photograph of Kusama in her St. Mark’s Place studio in New York, taken in 1970. She’s standing in front of what looks like a protest poster. She’s quite aggressively staring back into the camera, and she’s covered with – potatoes? growths? strange fruits? aliens? studded with little phallic forms, weighed down and decked out in them. They’re spilling out of her, making the photo both comic and uncanny. They’ve conquered her vanity case, and hang merrily polka-dotted from her leg on a strip of material. They’ve spread across the floor, and, like a blinding prophetic revelation of the kind of Sex and the City cliché we’ll be blandly meant to swallow 30 years later, they’ve taken up fetish-residence in a couple of pairs of shoes.

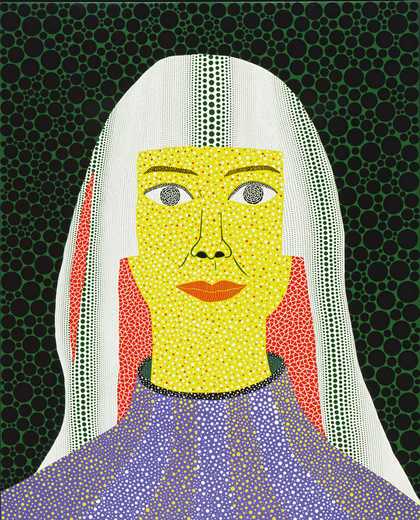

The third, Self-Portrait 2008, is a work of brights and darks whose eyes are like mesmerising mazes in a portrait that demonstrates the construction of identity, pointing towards the simultaneous workings, in the making of a self, of notions of individual and aggregate.

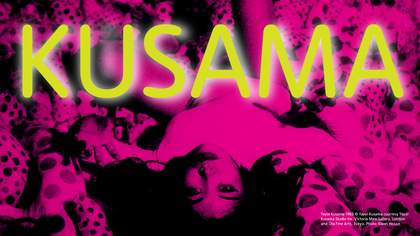

Yayoi Kusama

Untitled 1939

Pencil on paper

25 × 22 cm

Yayoi Kusama in one of her New York studios 1970

Photo: Thomas Haar

Yayoi Kusama

Self-Portrait 2008

Acrylic on canvas

227.3 × 181.3 cm

Nets and dots; obsessively repetitious-seeming forms that shapeshift as you look at them, from dot to fish to sperm to egg to coin to cell to microbe to planet; funfair halls of mirrors which turn surfaces, rooms, into a reverberating parody of light, dark, fluidity, eternity; huge gaudy monstrous flowers whose centres open to cartoon-surrealist eyes – this is the trademark stuff of Kusama. Her versatility with form over her 70 years of painting, sculpture, poetry, fiction, performance, abstraction and figuration, monochrome and psychedelia can now be seen for the lifeforce, the immense energy, it simultaneously celebrates, deprecates and is.

‘From a very early age I used to carry my sketchbook down to the seed harvesting grounds. I would sit among beds of violets, lost in thought. One day I suddenly looked up to find that each and every violet had its own individual, human-like facial expression, and to my astonishment they were all talking to me’ (Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, page 62). From the start she’s been an artist fascinated by the attractions and horrors of multiplicity and individuality in the universe.

Any self-absorbed culture could learn from the parody and the darkness in her work, much like the mid-twentieth-century New York art scene learned from this unlikely magician-figure arriving in the late 1950s from a defeated Japan, carrying ‘60 silk kimonos and some 2,000 of my drawings and paintings’, with as much illegal money as she could hide stuffed into the linings of her clothes, suitcases, shoes (her first phalli?), and with a generous, mildly discouraging letter from Georgia O’Keeffe in her pocket.

She’d written to the American painter because she’d chanced upon a book of her work in a second- hand shop in the small town she grew up in – a near-impossibility, a woman artist. O’Keeffe had tried to interest her own dealers in the pictures of this young Japanese artist who’d begun corresponding with her about how she wanted to leave Japan and come to the States: ‘If you do get here, I hope it will seem to be worth your trouble,’ wrote O’Keeffe dryly from New Mexico.

But Kusama, drawn to oppositions, had already become a painter back home, regardless of parental and cultural pressures, and had got used to making her art out of whatever came her way (the sacking used in her family’s industrial seed business for canvas, the mud from the river or household paint for making the picture). She began by creating her ‘infinity nets’ – huge canvases whose repeating markings, made by a repetitive flick of wrist and brush, ape monotony and mechanism, but vibrate into visual kinesis and disperse any notion of sameness or mechanised uniformity as soon as you pay them attention.

My desire was to predict and measure the infinity of the unbounded universe, from my own position in it, with dots – an accumulation of particles forming the negative spaces in the net. How deep was the mystery? Did infinities exist beyond our universe? In exploring these questions I wanted to examine the single dot that was my own life. (Autobiography, page 23).

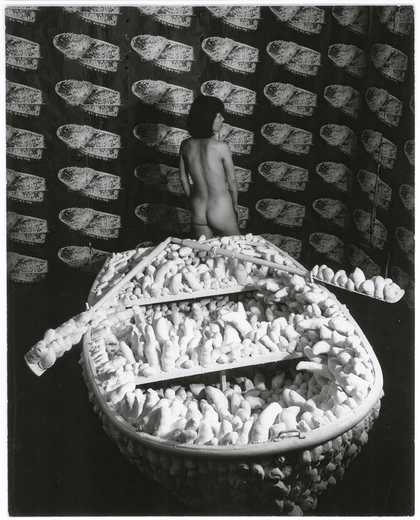

This took the kind of chutzpah you can clearly see in the 1970 St. Mark’s Place photograph: ‘Bring on Picasso, bring on Matisse, bring on anybody! I would stand up to them all with a single polka dot’ (Autobiography, page 24). No wonder she was soon covering everything with phalli: chairs, sofas, a stepladder. Her Aggregation Rowboat 1963 makes proliferation and desperation the same thing, bristling with phalli like barnacles, like coral, like mould, several of these somehow rather comforting cushion-like phalli even precariously balanced in little groups on the oars. Kusama had herself photographed nude behind the stern for her Aggregation: One Thousand Boats show in 1963; her untrammelled body, with its back turned to us beyond the carbuncled boat, surrounded by the repeating, faintly phallic-headed shapes of some of the 999 photographs of the same boat on the walls of the installation, is a revelation of relief.

Yayoi Kusama posing at her Aggregation: One Thousand Boats show installation in the Gertrude Stein Gallery, New York 1963

She paints red polka dots in a river. She takes a dress, covers it in flowers and sprays it so that it resembles rags singed silver or gold: part fairy tale, part Midas nightmare. Is it minimalist? Psychedelic? Pop? Surrealist? It’s the comic/cosmic open eye of Kusama. ‘When the image is given freedom… it overflows the limits of time and space’ (interview by Gordon Brown, June 1964). For her, art is a fertile bleed, something which moves beyond the edges of the canvas, spreads on to the walls, the floor, out into the room, all over the self. Mindscape and landscape are the same in her work, a reminder that we are where we live, that we make what surrounds us as much as it makes us.

Italo Calvino, who, in Six Memos for the Next Millennium, saw the novel itself as ‘a vast net’, and who, in the postmodern era of information overspill, looked to art to reassure us of what meaning is and how it works, understood human language as ‘signs, packed as closely together as grains of sand, representing the many-coloured spectacle of the world on a surface that is always the same and always different, like dunes shifted by the desert wind’.

Can you fit infinity on a single canvas? Kusama’s work, from then until now, from ash to phallus to dot to eye, is all paradox and impossibility, presence that’s disappearance, despair that’s joyous, mechanism that’s human, lyricism that’s business, thanatos that’s lifeforce, art that’s madness. Does she contradict herself? Very well then, she contradicts herself. She contains multitudes.

Yayoi Kusama

I’m Here, but Nothing 2000

© Yayoi Kusama and © Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

Yayoi Kusama

Phosphoresce in the Daytime c.1950

Ink and pastel on paper

25.2 × 17.5 cm

Virginia Woolf, who in her own moments of madness heard birds sing in Greek, would have understood Kusama’s speaking flowers. Her most political work, the anti-war tract Three Guineas 1938, ends with a plea to all listeners to hear ‘the voices of the poets, answering each other, assuring us of a unity that rubs out divisions as if they were chalk marks only; to discuss with you the capacity of the human spirit to overflow boundaries and make unity out of multiplicity’. That sounds like Yayoi Kusama to me.