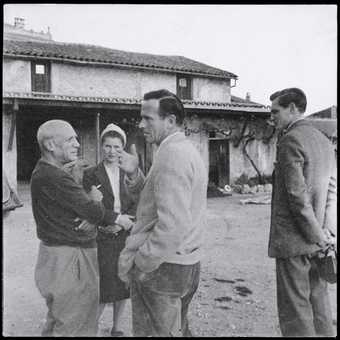

On 20 November 1947 the journalist and Labour MP Tom Driberg took Graham Sutherland to visit Pablo Picasso in Vallauris, southern France. Picasso was working in the pottery, painting and firing plates and pots, and Driberg recalled that he ‘took an almost child-like pleasure in showing them to us –”something useful and practical,” he said, ”something that everyone can take pleasure in”’ Sutherland was meeting a man widely regarded as the greatest living artist, and was already well-acquainted with his work and keenly aware of its implications. His admiration was lifelong, and two of the photographs that Driberg took of them together remained on display on his mantelpiece more than 25 years later.

Graham Sutherland’s first meeting with Picasso at the Vallauris Pottery in 1947, photographed by Tom Driberg

Courtesy National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

As a painter, Sutherland developed a personal approach to nature which, from English Romantic beginnings, drew increasingly on modern European art. He believed these two sources of inspiration were not only wholly compatible, but also that their interaction could produce original work. A visit to Pembrokeshire, Wales, in 1934 proved to be a turning point. ‘It was in this country,’ he claimed, ‘that I began to learn painting.’ However, even while he was immersing himself in the hills, valleys and estuaries of Wales in the 1930s and 1940s, he was already thinking about Picasso, and seeing his work in exhibitions in London and at the homes of friends and patrons. As early as 1936 he quoted him in an article entitled ‘A Trend in English Draughtsmanship’ – “I do not seek,” said Picasso, “I find”.’

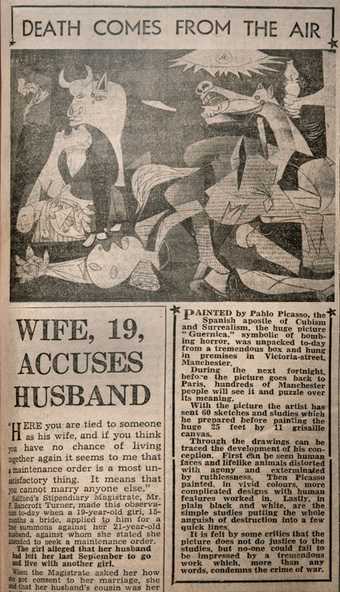

The 1938 exhibition of Picasso’s Guernica 1937 at the New Burlington Galleries in London astounded him. Sutherland later recalled that the work ‘seemed to open up a philosophy and point a way whereby […] things could be made to look more vital and real’. Only Picasso, he announced, ‘seemed to have found the true idea of metamorphosis, whereby things found a new form through feeling’. Sutherland responded by imbuing his landscapes and natural forms with an intense vitality, heightened by the contrast between light and dark, between depictions of life and decay. He explained that he was fascinated by ‘the tension between opposites. The precarious balanced moment – the hairsbreadth between – beauty & ugliness – happiness & unhappiness – light & shadow’.

Graham Sutherland

Thorn Head 1946

Oil on canvas

113 x 80 cm

© Estate of Graham Sutherland

Photo: © Prudence Cuming Associates

Books and illustrated art magazines, in particular Cahiers d’art, were another source of Picasso’s images and ideas. Copies in Sutherland’s collection are well used: tattered, with missing covers and loose pages, splattered with paint and bordered with fingerprints where his paint-covered hands held them as he worked. He evidently painted with reproductions of Picasso’s work on view.

Sutherland’s contemporaries recognised a connection between the two artists. In 1947 the painter Keith Vaughan (1912–1977) remarked: ‘What Picasso did to the human figure, Graham Sutherland is doing to the landscape. I think he is the first painter to relate the full discoveries of the twentieth century in France to the English Romantic tradition.’ In an interview in 2007, painter John Craxton (1922–2009), another Neo-Romantic, recalled that Sutherland was ‘wonderful’, because ‘he told me “you must invent”. It was a very good lesson for me, because it was very much like what Picasso was doing. He was also taking natural forms and reinventing them.’ For Sutherland, this reinvention occurred in forms he dubbed ‘paraphrases’, and his explanation of these clearly shows the lessons he had learned from Picasso: ‘The unknown is just as real as the known and it must be made to look so […] If I have felt that I must paraphrase what I see, it is because to do so gives me a shock of surprise – a new valuation of things. As if I had never seen them before.’

He felt that Picasso’s example confirmed ‘that one’s emotions when facing an object could transform that object and give it a new vitality, transcending ordinary appearances’. However, he insisted: ‘I do not think my pictures are very Picassoesque […] I am referring to the philosophical influence of one painter on another, not the technical one […] Nobody should ever copy Picasso.’

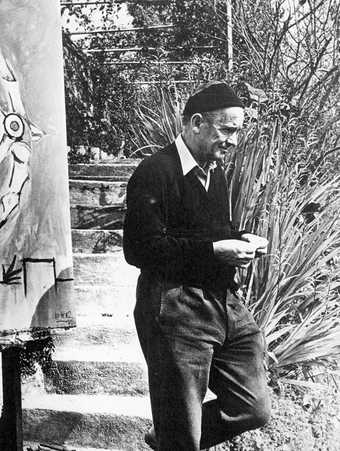

Graham Sutherland in his garden in Menton, South of France, c.1962

Private collection

Photo: © Tate Photography

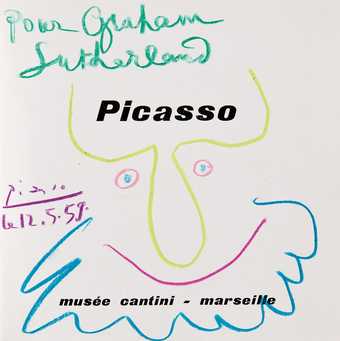

Picasso exhibition catalogue dedicated to Graham Sutherland, 1959

Courtesy Tate Archive

After meeting Picasso at Vallauris, Sutherland regularly returned to the French Riviera, buying a hillside villa at Menton, near the Italian border, in 1955. The Mediterranean coast offered him a multitude of new, inspirational forms, and palms, gourds and maize were all studied, dissected and reassembled in his work. His visits also provided further opportunities to meet Picasso, and their mutual friend, the art historian and collector Douglas Cooper, encouraged their acquaintance. Cooper sent Sutherland a telegram insisting that ‘Pablo longs [to] see you a [sic] Dimanche [on Sunday]’, and took one of his paintings to show Picasso, writing to Sutherland in September 1960:

I showed Mr Frog* to Pablo, who has for a long while been wanting to see something of yours in the original. He was delighted and spent a long time looking at Frog […] He put on spectacles and studied it very close and sent a special personal message to You: c’est très bien, je l’aime beaucoup, tu lui diras que c’est une peinture très sensible et très sérieuse [It’s great, I love it, tell him that it is a very sensitive and serious painting]. So there you are. And he was full of praise for the independence of GS, who does his own work and is like no one else.

The appraisal is acute: sensitive, serious and independent are insightful descriptions of Sutherland’s practice, qualities he aspired to himself, and the recognition of his endeavours must have been intensely gratifying.

Picasso’s art cast a long shadow, and many twentieth-century artists recognised the necessity of finding a way through and past his innovations. In a letter to critic Robert Melville in 1948, Sutherland wrote of Francis Bacon (of whom he was a key supporter at this time) that his work was ‘real & containing the germ of recovery & the possibility of a post-Picasso development’. This idea of a ‘post-Picasso development’ clearly shows the significance of Picasso to Sutherland’s concept of modern art and, inextricably, to his own place in that movement. It suggests that he viewed the Spaniard in particular as the agent of an artistic rupture; an upheaval that had fundamentally changed the way in which artists must work. Sutherland was striving to determine how artistic practice might progress in the aftermath of this. He was not interested in imitating Picasso’s achievements, but instead was struggling to learn the lessons they offered and thus find an original path for his art.