Alighiero Boetti announced his first exhibition in January 1967 by sending an invitation presenting a grid of samples of materials he had used to make his new works: electric wire, Perspex, camouflage fabric, copper, cork lettering, asbestos pipes. The show itself confronted its viewers with just as staggering an array of objects: PVC tubes, square pipes, a roll of cardboard whose centre had been pushed up to resemble a Tower of Babel, a lightbox inverted to cast a weird glow on the gallery floor, a sheet of camouflage like a found painting, a copper pyramid, a few monochrome panels with odd texts on them such as ‘The Thin Thumb’. Here was an environment as packed as a hardware store, but in which all the materials of northern Italian industry had been put to playful use.

Alighiero Boetti

Io che prendo il sole a Toriino il 19 gennaio 1969

Private collection

© Alighiero Boetti Estate by DACS / SIAE, 2012, courtesy Fondazione Alighiero e Boetti

In the next year Boetti would continue to abuse the materials of Turin: bending sheets of metal with river stones to resemble a panettone, covering panels with car paint that he named on their surfaces, stuffing a plexi-box with styrofoam, chipboard, insulation material and dry spaghetti. Serious materials made their way into absurd objects, but there was a critical aspect to all this: the artist opposed his work to the cleanliness of minimalism and to the mystical formalism of pre-war sculpture (Brancusi for instance), just as he distanced his production from the culture of design and commerce that surrounded him.

It was only after Boetti’s first outings that Germano Celant coined the term Arte Povera, and though the art historian and curator included the artist in his shows, Boetti was always pretty ambivalent – if not hostile – about the idea of a new movement. Boetti’s Manifesto presented a list of young Italian artists, each accompanied by a series of indecipherable symbols. Whatever these stood for, no single artist shared all his attributes with anyone else on the list. By late 1968, Boetti would send up the hardware store aesthetic of Arte Povera with an anarchic installation in Amalfi in which he gathered random objects together, each one labelled with a sticker reading ‘Property of Sperone gallery’. His next show presented a blank window frame leaning on the wall. Beside it on the ground there was a homunculus made with clumps of cement like ossified snowballs. He called it lo che prendo il sole a Torino il 19 gennaio 1969 (Me Sunbathing in Turin on 19 January 1969). This was an image of an artist as a slacker, refusing to work, and after the show he retreated to the studio to waste days pencilling over the lines of grid paper until each was covered. The work – Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione (Test of Harmony and Invention) – was as far as you could get from stacks of pipes and plastics, but it continued his rejection of Turinese ideas about work, and heralded Boetti’s later interests in time wasting and non-efficiency.

It wasn’t just in the sunbathing double that he re-imagined the figure of the artist. He continued to ask questions posed earlier in the decade by Manzoni – how could one deal with the artist’s signature? How could a young artist subvert the conventions of the ‘biographical text’ so often used to promote his or her career? How could you mock the ‘photographic portrait’ that often accompanied the artist’s catalogue? Boetti toyed with these forms of artistic promotion in a series of witty works, but asked a more serious question too: what conflicting roles were artists expected to have in late 1960s Italy, and how could these be challenged? He recognised that the artist was often pulled in opposite directions, expected to be a private creator and a public entertainer. Rather than mourning this condition, he took it as a kind of opportunity, presenting the artist as a shamanshowman, as a slacker and an intellect, as an everyday man and a unique individual with a ‘sixth sense’, a special capacity of insight.

Boetti’s first exhibition, at Galleria Christian Stein, Turin, January 1967

© The Estate of Alighiero Boetti, curtesy Paolo Bressano, Turin

The artist for Boetti was a figure of multiplicity and contradiction. He sent out postcards showing himself as twins, and made posters where he held his hands aloft, one palm outstretched and the other clenched into a fist. Famously, he chose to be known as Alighiero e Boetti. Most importantly, this understanding of the artist as a figure of multiplicity led him towards a radical idea of art production: a work could be authored by different people so it had a multiple character itself. He was not interested in collaborative production, where two or more people discuss and share ideas, but in split authorship, where the makers have no direct contact. Teams of students in Rome organised by a friend of Boetti’s filled in sheets of paper with biro strokes; Afghan embroiderers commissioned by an associate of the artist stitched his maps and word squares; postmen in Rome, Guatemala, Ethiopia and Kabul would mark his envelopes with frankings and other ink prints on top of the sequential arrangements of coloured stamps he had so carefully composed. People unknown to him would, therefore, be responsible for the appearance of his works – and sometimes these people had no knowledge that they were handling and adding to an artwork.

Alighiero Boetti

Codice: Eritrea libera (Codex: Free Eritrea) 1975

Set of envelopes, framed

46 × 86 cm

© The Estate of Alighiero Boetti, courtesy Anne Marie Sauzeau

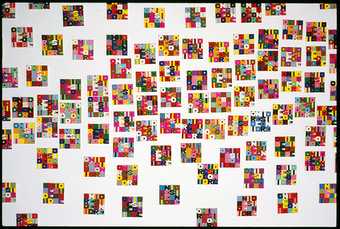

Alighiero Boetti

Ordine e Disordine (Order and Disorder) 1973

Embroidery

100 parts, 17.5 × 17.5 cm each

Private collection

© The Estate of Alighiero Boetti, courtesy Alighiero e Boetti Archive

Boetti had likened his processes of making the Arte Povera pieces to children’s games – stacking, grouping, and so on – and these games soon took new forms. In 1967 he made a series of boards with wooden counters arranged like dominos; similar works were produced in 1969 with coloured stickers on sheets of paper. He composed postal works where groups of envelopes featured all the possible permutations of three, four, five, six or seven different coloured stamps (the largest of these required 5,040 envelopes and 35,280 stamps). In the mid-1970s he made numeric drawings using grid paper to investigate escalating numerical progressions or sequences of alternations and additions. Sometimes he would create a clear set of rules to determine the composition of a series of works. These had to be followed, but there was still a great degree of freedom within them. The resulting pieces are close in conception to some of the serial projects of Sol LeWitt from the same period, but whereas LeWitt would present all the possible solutions to a problem, in Boetti’s works it would be impossible to realise them all within a lifetime. The viewer recognised that the work was only one solution, and that to fabricate all the solutions would take forever (or nearly forever).

In this respect, the Italian’s art was remarkably close to the poetry of the OuLiPo group, active at the same time. The Oulipans were also drawn to list-making, and to the art of classification, and so too was Boetti. One project, conducted with his wife Anne Marie Sauzeau, was to compile information on the 1,000 longest rivers in the world. This took them years and led to a book and two monumental embroideries. Before these could be made, the list of river lengths had to be completed and the order agreed, but the final works raised as many questions as they provided answers: were these lengths the ones measured from mouth to source? Along the left bank or right? At a time of flood or of drought? How could one possibly archive water that knows no boundaries?

The rivers project summoned up distant lands, but ten years before its completion, as early as 1967, Boetti had begun to think about the relationships between the studio and the rest of the world, fascinated by the maps of war zones that would appear as abstract forms on the covers of Italian newspapers. He transformed the maps into outlines etched on mirrored copper plates that would reflect the viewer, confronting him or her with the war zone and their own image in one plane. This was the earliest of his map works, now the most celebrated of his series.

Alighiero Boetti

Anno 1990 (The Year 1990) 1990

Pencil on paper mounted on board in twelve parts

100 ×100 cm each

© The Estate of Alighiero Boetti, courtesy Alighiero e Boetti Archive

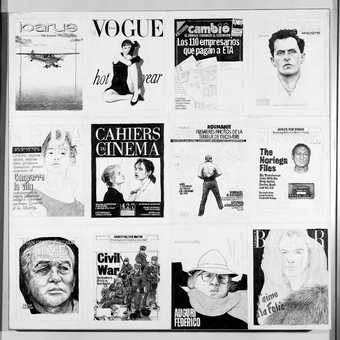

The first world map was a hand-coloured drawing, with each country on a school poster filled in with the colours of its flag. The next maps were produced by embroiderers in Kabul, where Boetti first travelled in 1971. This became a second home for him through the 1970s, a place of experimentation, discovery and refuge. With his associate Gholam Dastagir, he launched the legendary One Hotel in 1972, which became a place where he could hang out with other travellers on subsequent visits, while organising his production there. He tended to work with intermediaries, who would commission the women embroiderers. It sounds at first like a problematic way of producing art – using local labour and craft techniques to make works for a Western market – but Boetti’s approach was much more nuanced. Fascinated by the new approaches to colour in Afghan culture, he encouraged the producers to make their own decisions as they embroidered his word squares or maps. They became co-producers rather than fabricators, and their voices were present in the works, usually in bands of embroidered farsi text around the edges. Boetti had to stop going to Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion in 1979, but continued to work with communities of exiled Afghans in the northern cities of Pakistan. Around 1989 he visited Peshawar and met representatives of the mujahideen battling the Soviets. Their jihadi messages of resistance would be integrated into the large word squares and around the borders of the maps of this period. This alone is extraordinary: that his work would become a site where a political voice could be articulated – but not his own. Boetti was always on the lookout for 16- or 25-letter phrases that could fit into his word squares, but the most important phrase to enter his art was ‘Mettere al mondo il mondo’ (Putting the world into the world), which occurs in a group of biro drawings from the 1970s, encoded as a series of blank white commas like islands against an ocean of blue ink. This was a kind of guiding principle for his approach: the artist should not invent things, but instead bring those things that already exist in the world into the world of their work – stamps, magazine covers, office diaries, information about rivers. The phrase also suggests that artists could introduce things from all over the world into their work: Boetti used mosaics, kilims, embroideries, Japanese calligraphy. Through approaching art like this, the artist would ‘give birth to the world’, but never through wild flights of their imagination.

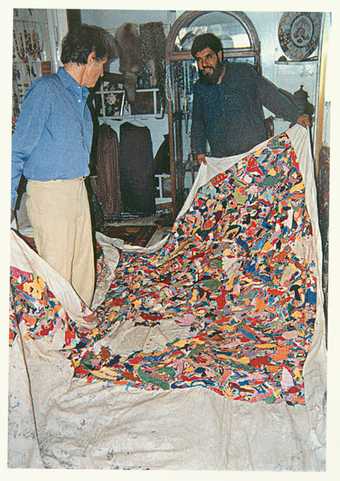

Boetti inspecting the production of a Tutto (Everything) embroidery in Peshawar, 1989

Courtesy Alighiero e Boetti Archive

Of all the objects Boetti made for his first show in 1967, the one that would seem most generative for later pursuits was the Lampada annuale (Annual Lamp). This was a plain looking oblong box, painted dark blue, topped with a sheet of glass. Looking in, one saw a giant light bulb. This illuminates for eleven seconds every year, and Boetti would publish photographs of the timer mechanism housed in the box to prove to sceptics that it really worked. Unless one is extraordinarily lucky, to encounter this object is to experience a sharp sense of anticipation and frustration, but leaving it, one wonders when it will light up, and whether anyone will be there to see it. Boetti gave time special qualities. He would later make works tracking time and wasting it – counting the chimes of a church bell, spending hours tracing over those grid lines, and so on. He hated the regulated clock time of factories, train stations and offices, adoring the time that rushes past or feels as if it stands still. Another of his favourite phrases was ‘to give time to time’. He played with dates too – turning banal office calendars into collages celebrating the numerals of a new year, and making watches where 3, 6, 9, 12 were replaced with 1/9/7/7.

Alighiero Boetti

Contatore (Counter) 1967

Collage on silk screen

42.5 × 62.5cm

© The Estate of Alighiero Boetti, courtesy Alighiero e Boetti Archive

Even through this briefest of accounts, it should be evident how generative Boetti’s work has been for younger artists. The projects of ‘relational aesthetics’ such as Philippe Parreno’s and Rirkrit Tiravanija’s The Land are unthinkable without the One Hotel; Pierre Huyghe’s choreographed performing lightboxes were sparked by the Lampada annuale (Annual Lamp). Mario Garcia Torres and Jonathan Monk in different ways research Boetti’s Kabul connections, and the wider ideas of working with craftsmen have informed the approach of Francis Alÿs. Peter Fischli and David Weiss waste time, while Maurizio Cattelan extends Boetti’s reflections on the identity of the artist.

But would these artists and so many others take so much from Boetti were it not for the extraordinary diverse textures and unusual beauties of his works? To encounter his art is not only to find a world of fascinating ideas, playful and critical, political and poetic, but to see the most stunning objects. I am thinking of a pink Mappa (Map) from 1979, made just as an interim Communist-leaning government had taken power in Kabul, a work where rose oceans surround the multicoloured continents, or the different shades of green embroidered thread in I mille fumi piu lunghi del mondo (The Thousand Longest Rivers of the World) 1971–7. Or a watercolour version of the Aerei (Aeroplanes), where pools of blue ink form a sky crammed with airplanes flying in every conceivable direction.

Or certain biro drawings, where the strokes of blue ink are so intense that one is reminded of a Barnett Newman painting and the wavy lines of hatched strokes recall reptilian skin. Or the drawings made in the studio by Boetti himself in the 1980s where you can find – on one sheet of paper – dabs of watercolour paint, frottage, red strokes made with Japanese inks and pencil tracings of postcards. And last of all, the monumental Tutto (Everything) embroideries, for which Boetti collected thousands of images from magazines, cut them out, laid them on canvas, drew around their outlines, and then sent the canvases to be embroidered in as many colours as the craftswomen had threads. You could spend an age looking at the Tuttos, giving time to time. Your eyes move around from shape to shape and colour to colour: if Boetti’s work makes one dizzy with the range of his ideas, then here the experience of shape and colour is just as dazzling.