Has something happened to our sense of scale? Big paintings – seriously big, that is, such as John Martin’s Joshua commanding the sun to stand still upon Gibeon 1816 at 2.34 metres wide, or Benjamin Haydon’s Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem 1820 at 4.5 metres – which were until recently regarded with embarrassment or outright scorn by art historians, now seem to be more deserving of attention. This is not to say that all such monsters will benefit from the turnabout in taste (to borrow William Vaughan’s useful phrase) that rescued late Turner from critical oblivion. No doubt when people go to the John Martin exhibition at Tate Britain there will be some raising of eyebrows at this opulent display of “the King of the Vast”.

But could our ability to contemplate such acres of canvas with more equanimity have something to do with our own expanded sense of image scale – from proliferating IMAX cinemas and giant plasmas to the miniature screens of our smartphones? Like Martin and his early nineteenth-century contemporaries, we’re living in a new age of spectacle, and of course there are many sceptical voices.

As indeed there were in Martin’s own lifetime. That contemptuous phrase “King of the Vast” appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine while Martin was at the height of his fame, and his nearcontemporaries Haydon and Francis Danby were engaged in what seemed to some a contest in sheer scale. Martin had launched his career in London in 1812 with a commanding upright picture, Sadak in Search of the Waters of Oblivion, that measured 1.83 by 1.31 metres, and just seven years later Constable decided to work on a similar scale, with the first of his “six-footers”, The White Horse 1819, followed by the now-celebrated River Stour series. Throughout this period, Haydon laboured on his Christ’s Entry, finally displaying it at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly in 1820. The fact that it was not shown in a “proper” exhibition hall, but among the freak shows and novelties of what would later be known as “England’s home of mystery”, did nothing to boost his cultural reputation. But was this what he wanted?

By the 1820s the English art world had clearly been infected by a search for impact through scale, with artists striving to immerse or engulf the viewer through a variety of techniques. But this didn’t happen in a vacuum, and it could be argued that the rising generation of young painters were responding to an explosion of new media in the surrounding world of late Georgian and Regency showmanship – much as the Pop artists of the 1960s responded to their new visual context. A crucial difference, however, is that 1960s pop culture is still very much with us, whereas the striking novelty of late Georgian public spectacle is little known, and hard to grasp from surviving illustrations.

The central feature of this new large-scale visual entertainment was undoubtedly the panorama, which arrived in London in March 1789, just four months before the storming of the Bastille in Paris ignited the French revolution. But even before the panorama, the French painter Philip De Loutherbourg had been attracting audiences to the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane with his remarkable scenic and lighting effects for Garrick’s productions during the 1770s. Like the great designer of Jacobean court masques, Inigo Jones, De Loutherbourg understood the importance of combining stage architecture and painting with lighting and even sound effects. And in 1781 he demonstrated this new stagecraft in an entertainment billed as the Eidophusikon, which was presented in Lisle Street, just north of Leicester Square. Seated in darkness and with accompanying music, the audience of up to 130 saw a series of painted tableaux through an aperture about 2 by 3 metres, which had movable elements and were animated by light shining through taffeta.

De Loutherbourg’s shows continued intermittently until 1786, and must have helped to develop an appetite for visual spectacle that would soon be further fed by the Irish-born artist Robert Barker, whose “interesting and novel view” of Edinburgh had proved so successful that in 1792 he opened a permanent building for the Panorama (a technique he had patented in 1787) in Leicester Square. The Panorama would continue for 70 years, becoming a familiar London landmark, with a sequence of giant paintings that began with London from the Roof of the Albion Mills (1792, 250m2), but soon moved on to record more exotic landscapes and eventually battles and military campaigns.

The fact that there are no surviving panoramas in Britain, despite London having launched what soon became a worldwide craze, has probably hindered appreciation of just how impressive this display can be. To visit Atlanta or the Cyclorama in Sainte-Ann-de-Beaupré in Quebec is to understand why the Panorama made such an impression. Sir Joshua Reynolds must have seen it before the Leicester Square rotunda was built (he died in 1792), but assured a friend that “it would surprise me more than anything else of the kind I have ever seen in my life”. And his successor as president of the Royal Academy, Benjamin West, who would contribute to the vogue for vast canvases with his Death of Nelson 1806, 2.47 m wide, hailed it as “the greatest improvement in the history of painting”.

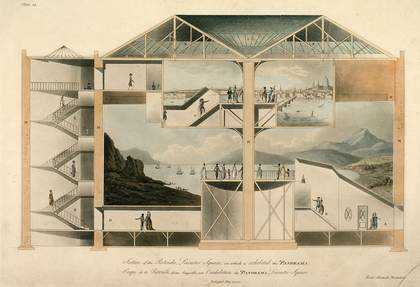

For Barker, the panorama represented “AN IMPROVEMENT ON PAINTING, Which relieves that sublime Art from a Restraint it has ever laboured under”. Much more than simply working on a larger scale, it was conceived as a carefully controlled experience, with light entering the rotunda from above and a viewing platform placing spectators at mid-height “in” the picture, although at a predetermined distance. The creators of panoramas soon discovered a number of devices that improved the illusion of looking into a three-dimensional space, such as placing foreground props at the edge of the painting. And when the battle panoramas were in full swing by the 1820s and 1830s, veterans would be on hand to offer guided tours of London’s panoramas, which now included the Lyceum and, from 1829, the imposing Regent’s Park Colosseum, which featured London from the Summit of St Paul’s, at 3,660 m2, and the city’s first hydraulic lift to bring people to its viewing gallery. A keen visitor to these spectacles was the Duke of Wellington, who could be found reliving some of his victories (and who also had a season ticket to Madame Tussaud’s waxworks).

One further novelty was still to come: the diorama, which arrived in London from Paris, opening in September 1823 in the newly laid out Regent’s Park. Again, the diorama resulted from a painter who wanted to “improve” on mere canvas or fresco. Louis Daguerre is, of course, much better known in media history as the official co-inventor of photography (with Joseph Niépce in 1826). But he was already working on panoramas, and was an accomplished painter of atmospheric landscapes when he launched the diorama in Paris in 1822. Like the Eidophusikon, this seated its spectators, who were provided with a series of changing views, painted on both sides of a large translucent canvas set at a distance of some 15m, with shutters that controlled the play of light on it. In the elegant purpose-built London building, designed by Augustus Charles Pugin, 200 people could witness a gradual progression of lighting effects, from sunlight to cloud, on Trinity Chapel, Canterbury, or on Holyrood Palace, or even the emergence of “Ruins in a Fog”. And by means of a rotating viewing platform, they could be transported magically from one such scene to another.

Cross-section of the Rotunda in Leicester Square in which the panorama of London was exhibited (1801)

Courtesy The Bridgeman Art Library

The effects of the diorama were judged highly artistic and answered to a growing taste for such scenes, encouraged by Romantic poetry and novels. London’s first omnibus service linking Paddington railway station with the City ran through Regent’s Park and carried an advertisement for the diorama, reinforcing the link between new forms of transport, especially the railway, and an appetite for landscape viewed in motion. Daguerre’s diorama was quickly imitated by other operators, notably Thomas Hamlet’s “British Diorama” in the Royal Bazaar, opened in 1828 on Oxford Street, and the term began to be applied to large paintings, especially John Martin’s apocalyptic scenes.

But the tide of aesthetic opinion was now running against such displays, however popular they proved with the public – which may, of course, have been the problem. The Eidophusikon, the panorama and the diorama had all started as relatively expensive entertainments, specifically advertised to “the nobility” and genteel society, but the last two had gradually become cheaper and catered for ever larger audiences, with the Oxford Street diorama providing shopping opportunities (as it still does, with the site now occupied by Marks & Spencer), and the Colosseum serving as a backdrop for fashion plate illustrations. The Egyptian Hall, which had previously displayed large paintings ranging from Haydon’s and Martin’s to Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa (shown to acclaim and profit in 1820), would specialise in magic displays under Maskelyne and Cooke and eventually become a cinema. Similarly, the Royal Polytechnic, once home to the most elaborate magic lantern shows of “dissolving views”, would host the first demonstration of the Lumière Cinématographe in 1896, and also become a cinema.

The Geometrical Ascent to the Galleries in the Colosseum, Regent's Park (1829) Aquatint

28 x 22 cm

Courtesy Guildhall Library, City of London

The association between, let us call it, panoramic painting and cinema has hardly worked to the advantage of either form. Where massive biblical scenes by Martin are often read today as “sources” for biblical epics such as those of Cecil B. DeMille – as indeed they were, along with an eclectic range of other nineteenth-century art – so this link has rebounded on their reputation as art. But that reputation was already under attack as early as the 1810s, when some critics and especially painters noted that the panorama aimed at “deception”, unlike the true landscape or topographical artist. Later in the century, John Ruskin would drive a sharp wedge between artists he considered “merely vulgar and stupid panorama painters” and the true panorama, where “the real old Burford’s [Barker’s successor in Leicester Square] work was worth a million of them”.

Today we may be better equipped to take a less judgmental view of the complex history of visual spectacle since the Enlightenment. Not only has painting undergone countless transformations and reinventions since Ruskin, but its “shadow history” of assisted or simulated spectacle, essentially based on controlled or projected artificial lighting, may also be appreciated in its own right. We don’t have to dismiss Martin as a “panoramist”, nor patronise his awe-inspiring paintings as IMAX avant la lettre – we might just be able to see them for what they were, and are, in the long history of the image.