Gerhard Richter was one of the first German artists to reflect on the history of National Socialism, creating paintings of family members who had joined, or had been victims of, the Nazi Party. In the late 1980s, looking back to the history of radical political activity in West Germany in the 1970s, he produced the fifteen-part work October 18, 1977 1988, a sequence of black-and-white paintings based on images of the Baader-Meinhof group. Richter has continued to respond to significant moments in history throughout his career. One room of the Tate Modern exhibition this autumn will include September 2005, a painting of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York in 2001.

The paintings of Gerhard Richter have provided one of the most spectacular and seductive models of what the medium can do for many art students over the past three decades. Taking in also his sculpture, printmaking and masterly drawing, each work seems to spring directly from the complexity of the contemporary world, executed with an extraordinary, magical technique. For me, as a painting student in the early 1990s, a Richter exhibition was as exciting as going to the cinema. His method of blending paint to create a smooth, photographic surface, known as dry-brushing, combined with the impression that any image could be fed into the machine of this technique and come out as good-looking art, opened up a whole new landscape of painting. Yet any attempt to emulate this process generally leads swiftly to the realisation that technique is only one ingredient of the Richter-effect. The dry-brushing is merely the final stage in image making that begins with something far more complex, an intertwining of personal and political history.

Gerhard Richter's studio in Cologne showing work from the Cage series in progress (2006)

Courtesy Gerhard Richter Studio

It was Richter’s luck to have been born in the 1930s as Hitler came to power, in that he was too young to suffer the long legacy of “collective guilt” for war crimes, yet still able to draw upon it as a source of inspiration and imagery. He has made works based on his experiences of growing up during the Third Reich and witnessing the upheavals of war, in particular the fire-bombing of Dresden; of his years as a student in communist Dresden; and of his defection to the West in the early 1960s. In his later work elements of his private life – marriage, divorce, fatherhood – take their place alongside reflections on the ongoing traumas of national history, from political violence in Germany in the 1970s to international terrorism in the twenty-first century. It is Richter’s ability to match the vicissitudes of personal and political history with an endlessly inventive technique that makes him such a compelling example for younger artists – and also such a terribly hard act to follow. For artists at least, to be wished “interesting times” is not a Chinese curse.

It is understandable that someone spending the first 30 years of their life first under Nazism, then Eastern Bloc socialism, would develop an antipathy to all forms of ideology. From the moment he moved to the West in 1961, Richter cultivated this antipathy to an extreme – but not as indifference, rather as distance. In his paintings of the past, for example the famous portrait of his Uncle Rudi, derived from a snapshot of the sitter relaxed and smiling, in full Nazi uniform, to images of contemporary consumer life culled from illustrated West German magazines, Richter holds all of his sources at the same arm’s length. He is never exhorting us to think this way or that – make up your own mind, if such a thing is possible, his work seems to say.

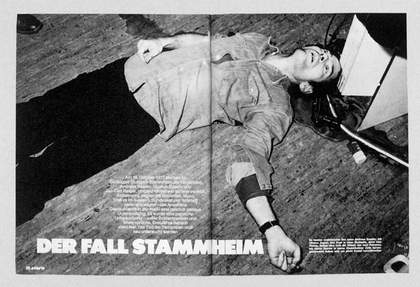

Andreas Baader, dead, October 18, 1977

Courtesy Gerhard Richter Studio © Stern as published in Stern, 30 October 1980

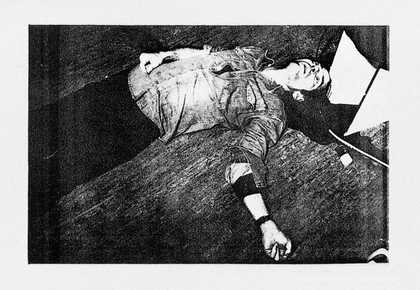

Andreas Baader, dead October 18, 1977, photographic model for Man Shot Down 1 and Man Shot Down 2, from Gerhard Richter’s notebook

© Gerhard Richter, courtesy Gerhard Richter Studio

Gerhard Richter

Man Shot Down 1 1988

100.5 x 140.5 cm

Oil on canvas

Courtesy Gerhard Richter Studio © Gerhard Richter

In front of the October 18, 1977 cycle of paintings, dealing with the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group and the terrible events of the “German Autumn”, it is incredibly difficult to draw any conclusions at all. We are presented with a series of blurred, monochrome images, hauntingly faded and obscure in meaning. The date of the title is that on which two members of the extremist gang were found dead in the cells at the high-security Stammheim prison in Stuttgart. Had they committed suicide? And what had motivated them in the first place to perpetrate such atrocious acts against the society in which they were raised? Richter simply reproduces a series of images of the events: a portrait of Ulrike Meinhof; an image of a record player that was supposed to have been used to smuggle the suicide gun; a hanging figure; crowds at the funeral. Each painting is based on a newspaper photograph painstakingly selected for its lack of rhetoric, its absence of any moral statement on the events. The artist’s own view of the story is equally ambivalent: although he was critical of the gang’s actions, he was also aware of the deficiencies of the West German state, and the conditions that resulted in the terrorism. The October 18, 1977 cycle is perhaps Richter’s best known series, and is certainly his major claim to the status of a contemporary history painter. Its acquisition by the Museum of Modern Art in New York was extremely controversial, with many Germans considering it of such national importance that it should stay in the country. Yet the series stands unique in the artist’s oeuvre – he has not attempted anything on such a scale since – and is exceptional for its direct political content.

Considered as a whole, politics does not seem to provide the master key for Richter’s work, despite his many images relating to German history, past and present. If we want to understand the way in which he has matched a technique of painting with a way of seeing the world, it seems to me that we have to look in the opposite direction – not at the politics of history, but rather at the politics of nature.

Richter has written often about the role of nature in his work. He is concerned on the one hand with how his paintings and sculptures appear with the self-evidence of natural phenomena, but also with a resolutely secular understanding of nature as a brute mechanism, indifferent to human strivings and passions. Nature “in all its forms is always against us, because it knows no meaning, no pity, no sympathy, because it knows nothing and is absolutely mindless: the total antithesis of ourselves”, he has said. It is a strange formula, by which his own work becomes an alien and indifferent phenomenon, a source of marvel, but also perhaps of indifference, or even fear. A series of landscape paintings begun in the late 1960s were the first strong signal of this conception of nature. As the storms of May 1968 were breaking over the European universities and art academies, and his militant colleagues were issuing the edict to “stop painting!”, Richter embarked on a group of photorealist sea and cloudscapes that might easily be thought of as the most un-radical of gestures possible, a deliberately perverse reaction to the politicisation of every aspect of daily life.

Seascape (Cloudy) 1969 is a spectacular image that casts a backward glance to a Romantic tradition of nature painting. But unlike his forerunner Caspar David Friedrich, he omits any signs of human life – not even a distant sail to provide an element of narrative.

Gerhard Richter

Seascape (Cloudy) 1969

Oil on canvas

200 x 200 cm

Courtesy Böckmann Collection © Gerhard Richter

In these and other works, Richter seems to be saying that nature can rival, and indeed outdo, the drama of human life through its “absolute mindlessness”. But there is another side to this commerce with nature that is less pessimistic and austere. Successful works of art, he has written, are such “when they have a similar structure to and are organised in as truthful a way as nature”, and he compares them with natural things, “trees, animals, people or days, all of which are there without a reason”.

This notion of art as an equivalent to the processes of nature, rather than simply mimicking natural appearances – what might be termed an “intelligent” theory of art – is one of the less-developed themes of modern art writing. Clement Greenberg’s short essay ‘On the Role of Nature in Modern Painting’, written in 1949, is a concise summary of this tradition from Impressionism to abstraction. For Greenberg, the decisive step in modern painting was for art to stop attempting to look like nature, and rather to emulate its processes and structures: “When Picasso and Braque stopped trying to imitate the normal appearance of a wine glass and tried instead to approximate, by analogy, the way nature opposed verticals in general to horizontals in general – at this point, art caught up with a new conception and feeling of reality that was already emerging in general sensibility as well as in science.” The Indian art theorist Ananda Coomaraswamy had put it even more concisely in his 1934 book The Transformation of Nature in Art (quoting Thomas Aquinas): “Art imitates nature in her manner of operation.”

It was Richter’s great innovation to throw photography into this equation, and to treat photographs themselves as natural things – they “drop on to our doormats, almost as uncontrived as reality, but smaller”, he wrote. Photography offered a way of gaining direct access to nature. It also meant employing randomising procedures to generate imagery with a natural feel. This ranged from the use of a lottery to determine the position of swatches in his “colour-chart” paintings – increasingly ambitious works comprising grids of coloured rectangles – to the application techniques that mark his abstract works, an extreme example of which would be fitting a pencil in a drill bit to create wild, sprawling uncontrolled drawings.

Gerhard Richter

Cage 5 2006

Oil on canvas

300 x 300 cm

Tate collection © Gerhard Richter

And it was in his abstract paintings that these various ideas of nature evolved and coalesced. At the end of 1989, following the Baader-Meinhof cycle, Richter produced a series of large abstract paintings with richly encrusted surfaces, created by complex processes of paint application, scraping using a “doctor blade” (simply a long, straight edge) and repeated layering. These were simply titled November, December and January – as if the vast, dark surfaces could provide some equivalent, through analogy, to the extraordinary historical events of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of the Soviet empire and the reunification of divided Germany. A similar group of abstract works painted around 2006 are all titled Cage, which seems at first sight to suggest the sense of a closed interior, but may also refer back to the American composer and theorist John Cage, himself a disciple of Coomaraswamy, who inspired Richter from an early date.

Such large abstract works came to dominate Richter’s studio output from the 1980s onwards (although it should be said that the art students mentioned earlier were still hung-up on the photopaintings of the 1960s). Underlying them is a modern – perhaps, more accurately, post-war – experience of nature, not as a romantic overcoming, but as a terrifying dissolution of identity, and a source of profound scepticism. Nature is indifferent to human life. It uses us simply as vehicles for bacteria, sweeps us away in disasters and random mass extinctions, or just terrifies us by the sudden revelation of meaninglessness, the anti-epiphany made famous by Sartre’s sudden, terrifying vision of the twisted forms of a tree trunk.

Gerhard Richter

4,16, 256, 1024 (installation view)

At Galerie Zwirner, Cologne (1974)

Courtesy Galerie Zwirner, Cologne © Gerhard Richter

Such worrying sentiments may lead us to the real drama of Richter’s work. Beyond the question of the encounter of photography and history, is a broader question of the meeting of technology and nature, and a sense of nature not only as “brute” and unpitying, but also as itself threatened. Nature cornered by the modern world. In a series of paintings made since 2000, based on compute-rgenerated images of the interior of atoms, Richter brings the profound scepticism of his landscape paintings and vast abstract works together. The series focuses on silicate structures, artificially produced materials that reproduce the shimmer-effect of natural silicates, such as those found on the outer bodies of insects. The resulting paintings are both bland and terrifying, the lack of any human element making them almost impossible to look at or think about. Is this where we have come to? The paintings themselves provide no answer, and it is in other works, paintings of family life, for example, or the large stained glass window Richter made for Cologne Cathedral, that some solace, however temporary, may be sought. If the politics of nature is coming increasingly to dominate contemporary art, this may be the most visionary and influential aspect of Richter’s art for generations of art students to come.