In April of 2010 I wandered into the Museum of Art of São Paulo, and was quite unprepared for what I encountered. It was an exhibition of Max Ernst’s original 1933 collages for Une semaine de bonté (A Week Of Kindness). One entire floor was divided into large galleries, each painted a different bright colour – purple, green, red, blue and yellow. As I entered the first, I saw, hanging at a short distance from one another, a series of works on paper in identical sizes and formats. As I looked closer and read the wall labels, I realised the brilliance of Ernst’s decision to keep the pages uniform, for it made them into a commentary on the sort of publications he took his source material from. These were usually of the kind later referred to as “true crime” magazines, with violent stories, malevolent men and sexy, often semi-naked, women. By his subtle interpolations of dream-like elements, he made his own magazines.

The collages, 184 in number, were exhibited in Madrid in 1936, and then not seen again by the public until 2008. They were published in Paris in 1934 as a “roman” or novel in five volumes, but benefit from being seen in their original form, not only to appreciate Ernst’s famous ability with the collage technique, but also because the effect of viewing all the works together in a room adds immeasurably to the experience. They are divided into days of the week, with a colour and a “capital element” for each day (yellow covers the last three days). Sunday is purple, its element mud. Monday is green, its element water. Tuesday is red, its element fire. Wednesday is blue, its element blood. Thursday is yellow, its element darkness. Friday is yellow, its element sight. Saturday is yellow, its element is the unknown. In addition, each day has a theme, an image that repeats in variations throughout its particular series.

Une semaine de bonté is a collage novel, or a kind of precursor to today’s graphic novels. While it does not tell a story – there is no linear series of events that occur – still the restricted format and repetitions of imagery and subject matter give the collages a serial coherence. Also, the bizarre images – often scantily clad women encountering alien-looking men or animals, or unusual objects – can be seen as forebears of the work of artists making ’zines today.

The more I studied this work, the more I realised how pervasive Ernst’s influence has been for artists and graphic designers – and not merely those who actually make graphic novels and ’zines. I was particularly interested to see how fine artists were able to assimilate the alien populism into their more rarefied ways of working and the contexts within which their work is seen. Thinking of Une semaine de bonté as a graphic novel avant la lettre, it is intriguing to look at contemporary artists who take inspiration from popular imagery, such as comics and graphic novels, and possibly also from Ernst’s serial collage work.

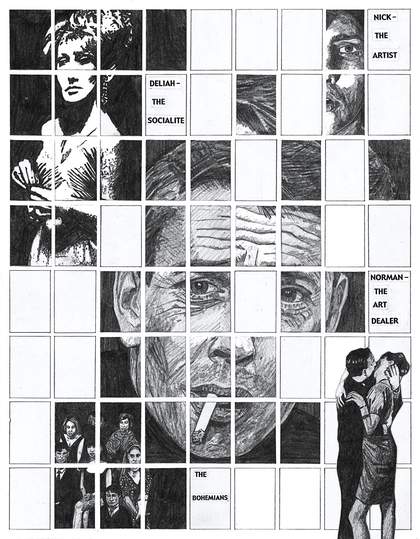

Olivia Plender

The Masterpiece – Issue 3, Evil Genius 2002

Printed comic book

38 x 28.7 cm

Courtesy the artist © Olivia Plender

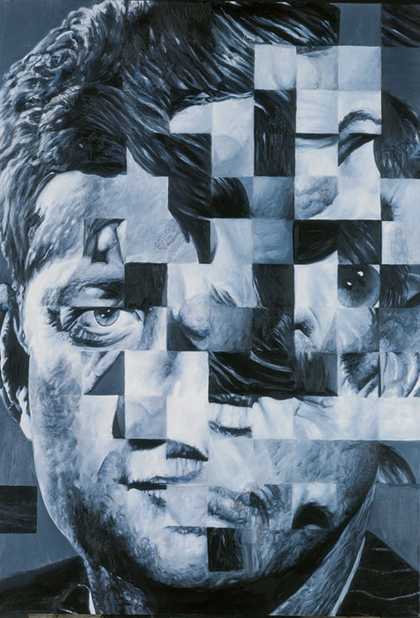

Jim Shaw

Untitled (Distorted Face Series: JFK) 1986

Oil on canvas

182.3 x 121.9 cm

Courtesy Simon Lee Gallery, collection Susan Hart © Jim Shaw

Jim Shaw and Raymond Pettibon, who came to the fore in the 1970s, have both worked with material from popular culture and have an art practice that draws on popular formats. In Shaw’s case, a lot of his early work depicted degenerate scenarios in pencil-on-paper comic-strip layouts. Pettibon does not use the strip format, but many of the personalities in his drawings – the tough guy, the jock, the druggy, the moll – come from pulp fiction and comics. They both transform this raw material, much as Ernst did, by unexpected juxtapositions of imagery. Although they do not use collage per se, and their technique may be rougher than Ernst’s, here is much of the collage sensibility in how they combine images, and there is a similar desire to undermine middle-class conventions.

Gary Sullivan and Olivia Plender make works in modes derived from ’zines, but take them into different, less narrative directions. Sullivan is a poet and artist living in New York, who has become known, mostly in the poetry world, for his hand-drawn comics, whose images come sometimes from things he observes, sometimes from the collective unconscious of popular culture. Many of his works are visible on the web, but he has also created art in the form of a comic book. In his comic book series Elsewhere, he accesses popular culture not from publications but from daily life. For Elsewhere #2, he took photographs of Coney Island Avenue, later transforming them into drawings. Although words are included, the nonlinearity of word and image links Sullivan’s comics to the sequences in Une semaine de bonté. Plender is a young British artist who decided to make use of the comic-book format as a way of increasing accessibility to her work. The Masterpiece Part 4 – A Weekend In The Country, available online, has the look of a ’zine. A conventional story taken from the nineteenth-century idea of the artist as tortured genius is illustrated by crudely drawn images based on nineteenth-century technical manuals and B-movie stills. A dreamlike logic often interrupts the narrative flow at moments of psychological crisis.

Other contemporary artists show the influence of popular forms, not so much in the format of their work, as in their treatment of the subject matter. Tom Phillips often paints on top of found photographic material, as in Ein Deutsches Requiem 1971, giving it the Pop look of a comic. He also isolates words from found texts, making them resemble speech balloons, although the words thus isolated read like modern poetry. Phillips may be most famous for having created a new book from an old one, which was also Ernst’s project. In A Humument, originally published in the 1970s, recently updated, and now available as an iPad app, he painted on every page of a Victorian novel he bought on a book stall, leaving a small stream of words visible from the original text. In this way, he created a unique artist’s book and simultaneously a new poetic narrative.

Juan Gomez and Paul McDevitt are two artists who twist recognisable imagery in ways that show the influence of popular print media. Gomez, born in Colombia and based for some years in New York, makes cartoon-like drawings that sometimes have an explicit nature. Although he gives his figures a sense of dimension, there is an equally powerful sense of flatness, evinced partially by the monochromes he uses for figures or background spaces, and partially by the lurid, unreal colours he chooses. His figures often engage each other in what seem like primal, cataclysmic encounters. British artist Paul McDevitt did a series of ten etchings in 2009 that unexpectedly use the fine art graphic medium to present subject matter that seems to be a melange of humanoid features taken from comic books of the Mad magazine genre.

Finally, a small group of artists has been able to have it both ways: they make work that is influenced by the serial, accessible nature of comics, but still remains abstract. Chris Martin is known for his large-scale paintings that often feature a single, biomorphic form, painted flatly, without illusionism. Interestingly, the colours and the forms call to mind backgrounds and shapes from comics, even though he does not use recognisable imagery. Amy Sillman, likewise, is known for her brightly coloured paintings with forms in them that feel specific, although they are not identifiable. Both artists have interests in books and the crossovers between painting and word. In one recent series of drawings, however, Sillman seemed to bridge the gap. Light bulbs, flashlights and human bodies were displayed in a sequence that did not tell a story, but had all the visual logic of one of Ernst’s sequences.

Although visually their work may seem quite different from Ernst’s in Une semaine de bonté, these contemporary artists partake of a similar attitude towards popular culture. Fascinated by it, they appropriate its tropes partially as a way to emulate its rapid communicative channels. Some are content to take a distanced approach, not commenting on, let alone attacking, the source from which their work has issued. Others use inherited forms, much as Ernst did, to expose the foibles of a class that dares not question its motivations and fears.