The Alice books are central to an English imagination that combines many strands of Victorian culture – hymns and nursery rhymes, facetious games and insider banter from the rectory and the schoolyard, canonical poems and learned notes and queries are milled and pressed together to make a perfect blend of comic brio. For a huge family living far from the metropolis, in not very affluent circumstances, illustrated magazines, such as Punch, were the principal vehicle by which pictures reached them, and they contributed a crucial element in the world which formed Alice.

As a boy, Lewis Carroll created family miscellanies in the style of Punch; although he had five younger sisters and three younger brothers who were all meant to pitch in to make the magazines, he was the eldest son and soon became the only contributor – of poems, jokes, stories and illustrations. The first of these, called The Rectory Umbrella after a favourite tree in the garden of the Croft, the family home, was produced in the year he left Rugby School, l849. It was followed by Misch-Masch, compiled during his first years as a young mathematics don at Christ Church, Oxford. Both magazines are packed with signature Carrollian puns and parodies, spun-out paradoxes and mock solemnities, in a mode that would become very recognisable in l865 when Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland appeared.

Carroll’s juvenilia also include lots of drawings and graphic marginalia. The frontispiece of The Rectory Umbrella, for example, shows a bearded old man beaming as fairies fly under the shelter of his umbrella. They’re bearing cradle blessings labelled “Good Humour”, “Knowledge”, “Mirth” and “Cheerfulness”, among other boons. Above them, comical grimacing goblins are hurling rocks – these are “Woe”, “Spite”, “Gloom”, “Crossness”, “Ennui” and “Alloverishness” (presumably from the woeful cry, “It’s all over”.) Most tellingly of all, the umbrella that is shielding the good sprites has written between its spokes, “Jokes”, “Riddles”, “Poetry”, “Tales” and, in the centre, “Fun”. The young Charles Dodgson was interposing a determined brand of fun between himself and unhappiness. He saw humour as somewhere, above all, to shelter; it had a purpose, and that purpose was intertwined with children and a child’s way of being. He transferred some of the material from these family magazines to the Alice books – the first lines of his poem Jabberwocky appear in Misch-Masch as a “stanza of Anglo-Saxon poetry”, written out in pretence runic script. His caricatures copy the conventions of framing, captions, print-lettering and calligraphy of the previous generation of cartoonists and illustrators (Gillray, Rowlandson), while exuding affable high spirits and occasional awful silliness in the style of Edward Lear, and impish charm in the manner of George Cruikshank, the first English illustrator of the Grimm Brothers’ Children’s and Household Tales.

Charles Dodgson's original drawing of rabbits

Alice with the Mock Turtle and the Gryphon

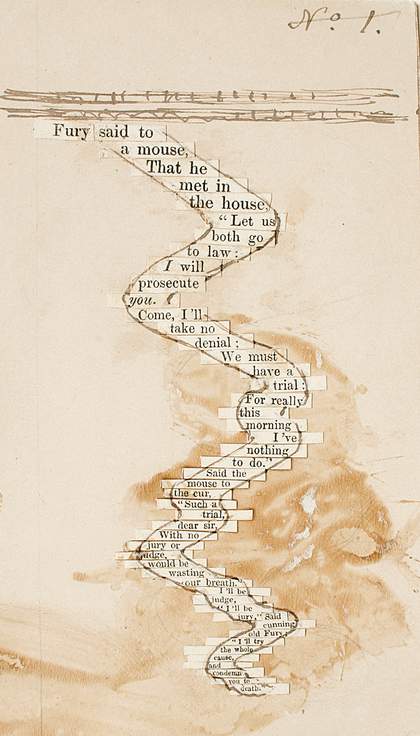

Proof sheet of the Mouse's Tail cut up and re-pasted in a curve

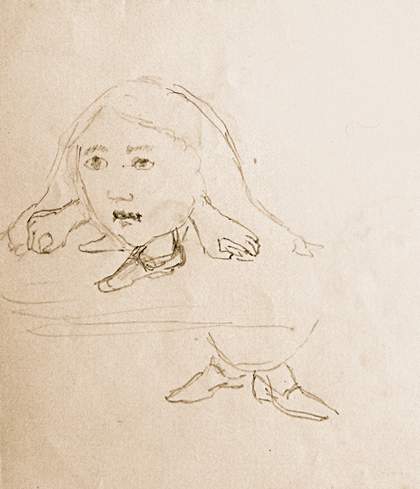

Charles Dodgson's sketches of Alice's head

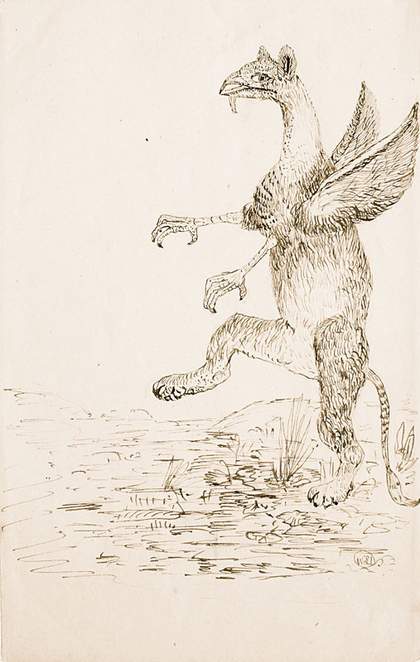

The Gryphon

The Giant Puppy

The menagerie of creatures Alice encounters in her wanderings after she has fallen down the rabbit hole have been remembered – and reshaped – from natural history books, but there are many other fabulous and comical beasts in the Alice books that are central to the stories’ appeal. Carroll’s original drawings include sketches for the White Rabbit, the Gryphon, the Mock Turtle and the Caterpillar, all of whom made it into the final cast. In one of his seemingly most finished drawings, he gives the Gryphon scales that make him look as if he’s a samurai in loricated armour. The Gryphon was a particular inspiration: an imaginary animal that is a riddle in itself, a hybrid, whose name is very close to “glyph”, the word for sign. As a mathematician, Carroll liked manipulating signs.

He hadn’t yet finished writing Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland when he began looking for an artist to execute his ideas. He knew he wasn’t able to do the work well enough himself, but he had very clear notions of what he wanted because he had tried to be his own artist, and failed. (When he took up photography, he became very skilled and an outstanding portraitist.)

At the time, the scabrous and ferocious cartoonists of the Georgian age had been replaced by a new generation of picture-makers, no less inventive or fertile, but more polite and less mordant in their humour. For the pages of Punch, and for other widely read graphic journals as well as novels, a remarkable band of artists produced huge amounts of work: George Cruikshank, “Phiz” and John Leech all illustrated Dickens, for example. However, in a step that reveals his acumen and would make the fortunes of his book, Carroll picked John Tenniel, a regular Punch caricaturist, who had caught his attention. Tenniel was overburdened with work, but eventually gave in to the author’s pressure.

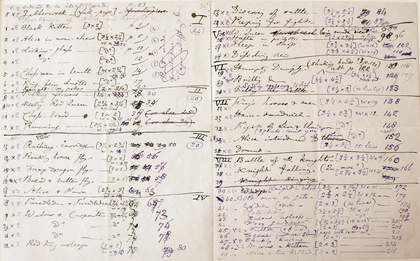

Carroll was not a split personality: the mathematician breathes through his writing, however elusive the connection might seem on the face of things. The charts he drew up for the sequence of llustrations include not only meticulous numberings, endlessly scratched out, redrafted and revised, but also exact dimensions of each image, to the quarter inch. He was methodical, capable of immersive concentration, and his eye for detail was needle-sharp. He wrote copiously to Tenniel to monitor his progress and control his interpretations. He gave him his own drawings to follow, and sometimes even sent him photographs for greater accuracy in reproducing the authorial thoughts. Carroll found Tenniel too slow and balky; Tenniel found the writer impossible. The artist was exhausted by the constant interference, and the exacting, finicky and obsessive and persistent communications. As Hugh Haughton comments in his illuminating introduction to the Penguin edition of both Alice books (1998), ultimately “it was a protracted and difficult as well as a productive collaborative process”.

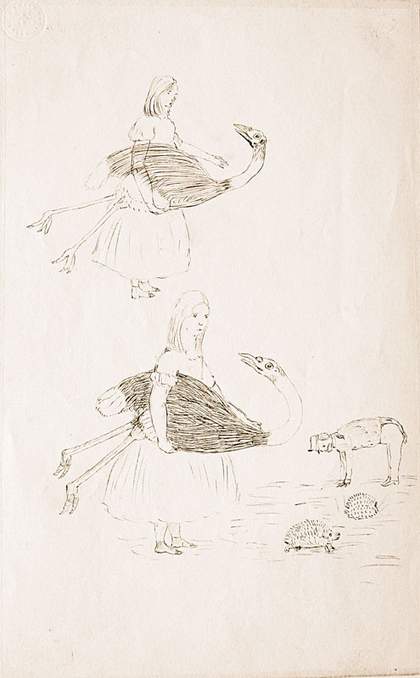

Tenniel argued for several changes to the characters as conceived by Carroll. The croquet mallets are ostriches in the original drawings, and the hoops are footmen bent over with the tails of their coats hanging down over their bottoms like an animal’s. Tenniel left them out. He told the author that a girl might manage a flamingo, but not an ostrich. Carroll agreed to this excellent instance of the logical imagination at work. Tenniel’s reworking of the ostrich-wielding Alice is one of the most memorable and witty of his Wonderland illustrations, as the little girl looks quizzically and deeply into the eye of the flamingo and its beak, neck and body make a question mark curve in her arm. With a foot on a hedgehog ball, she is puzzling out a way of using it as a mallet.

Alice with the Ostrich

Tenniel’s drawings mix human and animal with perfect fluidity, so that idiosyncratic features brilliantly modify zoological accuracy. Occasionally, Carroll’s drawing catches the mood very sweetly: the White Rabbit with his posy is a more touching wooer than Tenniel’s plumper bustling bunny. His puppy is soppy, despite its snout which is more pig-like than doggy. By contrast, Tenniel gives the scene drama, as a shrunken, tiny Alice tries to confront the colossus. Alice is scared that the puppy might be hungry, and, indeed, throughout both Alice books, the fear of being eaten surfaces, in the poems Jabberwocky and The Walrus and the Carpenter, and in the scene with the baby/piglet. Carroll was an antivivisectionist, and his preferred food seems to have been jelly, cakes and other tea-time treats. The climax of his literary fear of eating comes at the end of Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There when the leg of lamb toddles up to Alice with a carving knife and fork in its back and asks to be served up.

When I was a child, I found the Alice books disturbing and didn’t enjoy them until I was much older. The unease was stirred in part by their outlandish anthropomorphism, and in part by the ferocious authority figures. But the chief source of my anxiety was Alice’s changes of shape when she drinks from the little bottle and then nearly drowns in a pool of her own tears.

Carroll’s original drawings for Alice show his interest in her metamorphoses. He tends to use pencil very tentatively when drawing her, in contrast to the pen and ink sketches of animals, imaginary and other. His vignettes of the little girl are tiny and reticent; they render her feet and hands far smaller than they would be, and his lack of skill gives the figure a doll-like rigidity. They are never finished. When she is part of an imagined, dramatic scene, there is more of a sense of resolve. From the moment she falls down the rabbit hole, she experiences all kinds of changes, outside and in, as she grows tall and short and tall and short. Her later transformations even hint at the monstrous (at the Boojum inside her), when she nibbles at the Caterpillar’s mushrooms and shape-shifts, now shrinking until her chin hits the ground, now growing “an immense length of neck”. “She was delighted to find that her neck would bend about easily in any direction, like a serpent. She had just succeeded in curving it down into a graceful zig-zag” when a pigeon attacks her:

“Serpent!” screamed the Pigeon.

“I’m not a serpent!” said Alice…

In the preparatory sketches Carroll illustrates the episode with two drawings of Alice, one a monstrous squat head, with feet poking out from underneath it, as if painted by Hieronymus Bosch, and the other showing her neck stretched into a long column, even more stiff than his usual illustrations, perhaps on account of the patent phallic character of his fantasy. Tenniel did not make versions of them.

Charles Dodgson’s plan of the illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

The Alice books are tales of strictly personal quests, through the permutations of possibility that are almost infinite. “I wonder if I have changed in the night?” Alice muses. “Let me think, was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I am not the same, the next question is, who in the world am I? Ah, that’s a great puzzle!” This is, indeed, the great puzzle that has animated post-Victorian (and post-Christian) philosophy since Kant, and Carroll’s signal contribution was to place, at the core of the self, the experiences of fantasy and imagination.

His own inner processes necessarily elude, since the author never revealed himself. “Almost none of Carroll/Dodgson’s surviving writing bears the imprint of ordinary, subjective first person experience,” writes Haughton. “Not even his letters and diaries, where we might expect to find it.”

Carroll’s opaque, plural identity reproduces the view of the character in the Alice books as polymorphous, although he himself presented in so many ways a most conventional, and indeed stuffy, face to the world. One thing emerges clearly, however: he was decisive. Her creator understood his own strengths and realised he couldn’t draw as well as he liked, so he found an interpreter who did him proud. Tenniel took off from Lewis Carroll’s vision, and defined his heroine forever – for the first readers and then for generations of others who have seen her on stage, on screen and on the page.