I love lines, dots, drippy brushstrokes, polygons, blends, morphs and swirls. I love sticks with stripes on them. Looking at abstract art is for me like doing non-verbal philosophy, symbolic logic or non-number mathematics. It is like music, because it has a narrative without a story, without people: a drama without words.

My studio work is, for the most part, just me sitting, thinking and looking at what I have on the wall. Squares, dots, squiggles made of clay. There are shaped planes of wood or stretched canvas arranged not parallel to the ceiling and floor. I look and think, and I do a kind of obsessive measuring, cutting, dividing, adding, subtracting, sometimes with numbers; division and multiplication that I do in my head. No calculator. No pencil and paper. I imagine the images of other artists. These days I tap into Google to find something on the internet. My current obsession is Malevich, which is why many of my shaped canvases are slanting up and down the wall. I look at the everyday objects around me and mentally take them apart, cut them up and put them together in new ways. All of this is done in my imagination, until I finally get busy and actually make something.

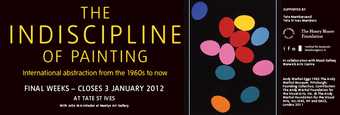

I am happy to see Peter Young’s work being shown in the Tate St Ives The Indiscipline of Painting exhibition. He is one of my early heroes: dots, lines, yes! That he was a part of the Los Angeles avant-garde as a child in the 1950s makes a lot of sense. His father, who studied with Albert Einstein, moved from Pennsylvania to Pacific Palisades with the family to work for the Rand Corporation.

There was a wonderful and significant group of post-war artists living in Los Angeles: designers, architects, film-makers, and composers that included Charles and Ray Eames, the architect Rudolph Schindler, artists John McLaughlin, Helen Lundeberg and Frederick Hammersley, as well as Arnold Schoenberg and the young John Cage. Young’s family was a part of this milieu. I lived there in the 1940s and 1950s, when that sophisticated high-culture was seeping into the southern California mainstream – so it was an influence on me, even as a child.

I love Andy Warhol’s Eggs 1982. This kind of generic abstraction is also of interest to me. I think that it often comes out of a discourse with the social community of art as much as out of aesthetic rumination. Warhol was primarily a figurative artist, and it makes sense. The abstract paintings, such as Eggs, as well as his “oxidation paintings”, are the result of his, (probably) non-verbal, engagement with social and critical aesthetic discourse. I have loved Warhol because I have always liked popular culture as much as high art, and was happy when I found that they were part of the same world. I saw his Campbell’s Soup Cans 1962 when Irving Blum showed them in Los Angeles at his Ferus Gallery in 1962. And I saw The Velvet Underground at the Fillmore in San Francisco in 1966.

David Reed is another favourite artist of mine. Again, it is about reference. For example: David often has the brushstroke as his subject. Using it as an image of a beautiful thing, that makes one begin to ruminate linguistically, to have a nonverbal mental conversation about everything, about painting and art, unless, of course, there is someone else around to talk to.

A great survey of painting such as The Indiscipline of Painting is for me a huge conversation, and this is the way I love to engage with art. I like to talk about it with other people, but I am also very happy to sit and look all around at painting after painting and allow them to speak to me, as I silently but verbally or non-verbally talk with them, say things to them and to myself. I can do this for a long time. And when I have a show of my work I hope that the people there will do the same thing. That is why I’ve started to make the chairs. I want people to sit down, hang out and look at the work for a long time, and talk to themselves and other people about it.