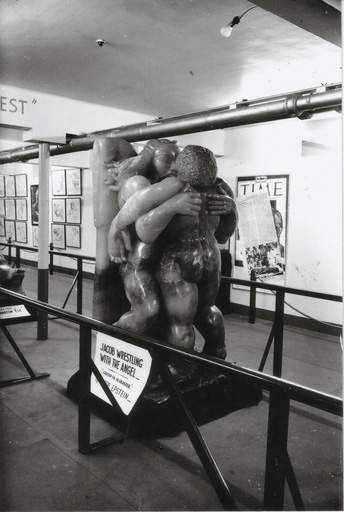

‘Epstein Turns Out New Six-Tonner’, read the Daily Sketch headline in an article preceding the first public showing of Jacob Epstein’s Jacob and the Angel 1940–1 at the Leicester Galleries, London, in February 1942. The carving met with a flurry of praise and sensationalism. The Daily Telegraph critic described it as ‘a craftsman’s tourde- force’, the Manchester Guardian’s correspondent enthused over its ‘complex interweaving of rhythms’ and the Daily Mail pondered: ‘Is this a miracle or a monstrosity?’

In the Old Testament book of Genesis, Jacob wrestles throughout the night with an unknown aggressor, who in the morning reveals himself as an angel and blesses Jacob for not giving up the fight. The story is interpreted as a contest between the flesh and the spirit. The artwork, with Jacob depicted exhausted, unable to stand if not for the embrace of the angel, is considered symbolic of Epstein’s own relationship with sculpture.

Jacob Epstein

Jacob and the Angel 1940–1 at Louis Tussaud’s Waxworks, Blackpool 1954

214 x 110 x 92 cm

© Estate of Sir Jacob Epstein

In 1908 the artist had been thrust into what he later described as his ‘Thirty-Year’s War’ with the British public, following the unveiling of his series of nudes for the façade of the British Medical Association building on The Strand, London (now Zimbabwe House), which the clergy and the tabloid press considered indecent. Epstein’s originality and his reluctance to compromise in the face of society’s prudish sensibilities made his work newsworthy. While the arts establishment refused to embrace him, the public’s disapproving curiosity made for attractive business elsewhere.

On the close of its showing at the Leicester Galleries, Jacob and the Angel made its first trip to Blackpool, repeating the journey and commercial success of Adam, which Epstein had carved from its twin half of alabaster in the late 1930s. Both works had been purchased by the London-based entrepreneur Charles Stafford. Jacob and the Angel was installed in an old song booth on Blackpool’s central promenade. The exterior advertised ‘Epstein’s Latest Sensation’ and ‘Adults Only’. The carving was placed on sand against a painted backdrop of dunes and palm trees. It was illuminated by coloured spotlights and accompanied by an American jukebox playing soft music and a loudspeaker giving an explanation of the work. An article claimed that for sixpence more one could view a mermaid: ‘not even a real one, but just some poor girl with her legs tied inside of a sack’, the writer concluded. Two years into its Blackpool showing, Stafford claimed: ‘Hundreds of thousands of people have seen what I think is Epstein’s greatest work.’

Jacob Epstein’s Jacob and the Angel in sand on Blackpool’s central promenade 1942

© Cyril Critchlow Collection, Blackpool, and Fylde Historical Society. Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool

After four blockbuster years on Blackpool’s Golden Mile, Jacob and the Angel was shown on London’s Oxford Street. To entice the public, along with the usual ‘sensational’ advertising slogans was a gramophone record from which the voice of Stafford questioned: ‘Do you think it is beautiful, or do you think it is shocking?’ He claimed that in just ten days the carving had earned £500 in admission fees and was seen by more than 50,000 people. Post-war blitzed Oxford Street was being turned into London’s very own Golden Mile, and other notable ‘cultural attractions’ dotted along it included ‘The Giraffe- Necked Women’ and ‘War in Wax’, in which for an additional charge one could view ‘The Horrors of the Concentration Camps’.

Stafford sold his Epstein sculptures, which now also included Consummatum Est 1936–7, soon after. Jacob and the Angel was exhibited with Adam in a seaside amusement area in Durban, South Africa, before returning to Blackpool, where in 1954 the three carvings were purchased by the town’s Louis Tussaud’s Waxworks. Installed in the attraction’s basement beneath a rather large heating pipe, they were joined by the artist’s earlier work Genesis1931 in 1958. Although Epstein had attended the opening of the first Blackpool showing of Adam in 1939, he would protest at what he described as the ‘cheapjack and vulgar manner’ in which his work was continually exhibited and criticise the lack of effort made by Tate to acquire it.

At the time of buying Genesis, the Tussaud’s manager stated: ‘We shall keep Genesis on show until she loses her drawing power.’ That event occurred in 1961, when all four carvings were purchased and ‘rescued’ by a consortium led by Lord Harewood to join other Epstein works in a retrospective at the Edinburgh Festival, before being shown at Tate later the same year. As the public’s curiosity over Epstein’s work dwindled, it was finally being embraced for its pioneering modernity. Jacob and the Angel was acquired by Granada Television in 1962, and for many years loaned to Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral and the University of Liverpool. It was finally purchased by Tate in 1996.