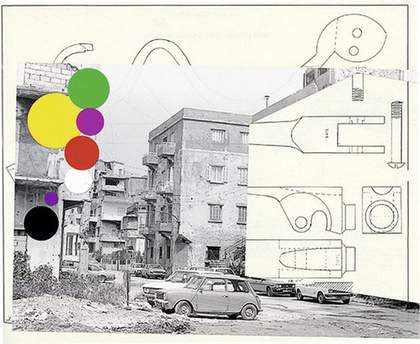

Camille Zakharia

Hut 15 Muharraq, Bahrain 2010

Archival inkjet print

56 x 56 cm

Courtesy Galerie Lucy Mackintosh, Lausanne © Camille Zakharia

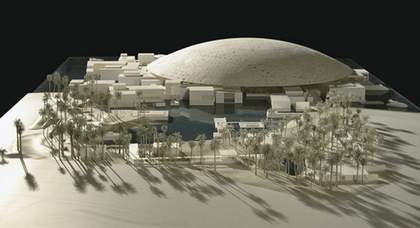

Model of Jean Nouvel’s Louvre Abu Dhabi on Saadiyat Island

© Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Courtesy Louvre

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie: There is a common assertion, whether it’s right or wrong, supportable or not, that the contemporary artworks that have been produced in the Middle East over the past ten to fifteen years are quite heavy on politics, more so than in other regions. I think maybe you can approach this assertion several different ways. You could say it’s a matter of interpretation: that certain curators and critics over-emphasise the political content of the work that’s coming out of this part of the world; that they look to the art for what it tells them – or confirms for them – about various conflicts in the region. In effect, they instrumentalise the work. Or you could say it’s a matter of selection: that institutions and curators are immediately drawn to political work at the expense of everything else that’s out there. The assumption is that what audiences, particularly those outside the Middle East, really want to see is how the region’s troubles and tragedies are reflected in or expressed through artistic practices. So you end up with a really distorted representation of what’s happening artistically. Or you could say that it’s precisely the politics of the Middle East that shape the forms and strategies of artistic practice. Is contemporary art from the Middle East more political than from elsewhere, or is the work so politically loaded because the region itself is so politically charged?

Vasif Kortun: Quite a lot of work is interested in forms of narrative, producing meaning from different angles, engaging in the present, and that seems to come across as political, or is seen as political. I think if you asked that question about other places, for example the Balkans ten years ago, you’d get a similar answer. It’s not about the art from one region or another being more political. It’s about the position from which we ask the question. The people who pose that question seem to be asking it from a “centralist” position where there is actually a certain gamut of art that works in a particular way. I don’t think it’s a good question to ask. It isolates, and actually marginalises a context.

Kader Attia: In one way, I agree about the central position of who asks the question. But we also need to remember that the Middle East, from Morocco to Tehran, is an area where the presence of political authorities in everyday life (both the local actors, as in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia, etc, and the Western ones, as in Iraq for instance) and strong censorship systems gives artists (including writers, directors, etc) only little room for contestation.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie: What about the category itself? What does contemporary art from the Middle East mean? How has it been constructed? Is it a field of artistic production? Is it tied to a certain art historical lineage? Is it a market? Is it a larger infrastructure that includes a market, museum projects and different funding bodies? Given that all of you live in different cities, work in different ways and deal with different state systems, how did you see yourself or find yourself in this category?

Vasif Kortun: That’s a tough question. For me, it is predicated on the context of Turkey in particular, because having come from a place that actually occupied the region for a very long time – I mean, all except Iran – there is an historical trajectory. But up until almost the end of the 1990s, there was very little visible give and take between Middle East countries. The region did not exist for practitioners in Turkey. The order of discourse was vertical, in the sense that borders were closer to New York than Cairo, or wherever, depending on what the imagined power centre was at the time. After 1989 the Balkans came into focus following the break-up of the Soviet states. That was the watershed. It changed everything, which also made it inevitable that practitioners would start paying attention closer to home. I did, at least. In the past decade the region became in many ways the subject of great interest. This meant I was able to orientate my institution, the Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Centre, towards establishing very close links with places such as Ashkal Alwan in Beirut, or the Townhouse Gallery of Contemporary Art in Cairo – to start residencies and try to build relations with places that one feels much closer to. Incidentally, I don’t go to Europe any more, almost never. Even the travel routes and the context have changed. This all started around the time of 9/11, or right after it. Now we see a completely different situation in which we have to navigate everything differently.

Wael Shawky: Usually I feel defensive of the category, of course, but actually I felt it most when I was in the residency programme at Platform in Istanbul. I lived in Mecca during my childhood, and then I came to Egypt. Most of my work deals with ideas of nomadism, emigration and religion. I hadn’t been aware of any pressure to deal with or try to define an identity – of coming from an Islamic country, or from the East or the West. But I felt this tension during my stay in Istanbul. I didn’t make too many pieces in Istanbul, just The Cave (2005). I was trying to translate my experience there. That was around the time when everyone was talking about Turkey’s bid to join the European Union. At the same time, it is an Islamic country – you go to the mosques and you hear people praying. But then again, most of them don’t understand exactly what they’re saying, because they don’t speak Arabic. All these questions made me think back to my childhood in Mecca.

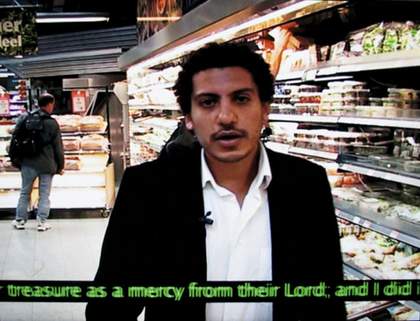

Still from Wael Shawky’s The Cave (2005)

Courtesy Galerie Enrico Navarra © Wael Shawky

Kader Attia: The situation is a little different for me because Algeria is a country that has been colonised for most of the last 2,000 years of its history, by the Romans, the Arabs, the Ottomans and the French. This idea of categorising an identity, such as Arab art world or contemporary Middle East art scene, is actually very French, something that developed during the Age of Reason with René Descartes. I fear the idea of giving a name to an area as huge as the Middle East. Edward Said said that the Orient starts in Rabat and goes to Tokyo. So I don’t regard my work as being inside of or beyond any frontiers or boundaries of the Middle East. I try to be an artist first.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie: In the period after 9/11, and before all the new museum projects were announced in the Gulf, institutions in Europe and North America seemed to become, very suddenly, interested in doing exhibitions of contemporary art from the Middle East. How have you grappled with that interest in your work? Have you tried to frustrate or complicate the expectations involved?

Kader Attia

The Landing Strip 2000–2

C-type print

Courtesy Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris © Kader Attia

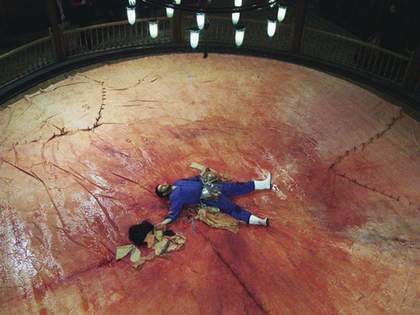

Figure #63 from Wael Shawky’s film Cabaret Crusades: The Horror Show File (2010)

Courtesy Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut © Wael Shawky

Kader Attia: I don’t try to fulfil or frustrate any expectations. When I am invited to participate in an exhibition, should it deal with religion or the Middle East, or with any other theme, I first read the statement of the curator and see if he or she tries to tackle questions that seem interesting to me, or that I feel linked to. That will be the reason why I take part in a project. I have to feel 100 per cent concerned by what the curator is trying to do. As an artist, my main concern is to raise questions, with no specificity of geographical area or religious background, even if these areas and religions are part of who I am. This will show through my work, but not in a literal way.

Wael Shawky: I have been involved in many shows under the banner of Middle Eastern art and Islamic art, etc. And I have started to refuse to take part in them. Many artists now are doing the same. Because of 9/11, this interest touches the political or religious aspects I’m using in my work. But it’s because I’m coming from this religious background in Mecca that my work is dealing with these topics, so I don’t think I feel the problem myself. At the same time, of course, I have to reject this interest, as a political position.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie: Let’s look at the rise of these museum projects in the Gulf, such as the Guggenheim and the Louvre in Abu Dhabi, and Mathaf, the Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, and also the new sources of funding for production in the region, such as the Sharjah Art Foundation’s programme, or the number of commissions for the Sharjah Biennial, for Art Dubai, or for the opening of Mathaf. The focus of Mathaf’s collection is on twentieth-century modernism, but it opened in December with the exhibition ‘Told/Untold/Retold’, which featured 23 newly commissioned works by artists “with roots” in the region. If your work were to be acquired by these museums and added to their permanent collections, would you feel that it would be at home there, however loaded the term home may be?

Vasif Kortun: I thought you were going to be facetious and say, would you feel your works would be marginalised! From the way I look at it, it is better for an artist’s work to be in a regional public collection than in the Tate Collection.

Wael Shawky: I don’t have a problem with that, honestly. I don’t even have a problem if these museums organise those kinds of shows with Middle Eastern themes that I was just talking about, because I think it’s very important to start with this, somehow. Then, in time, it will change. I think it’s fine. Contemporary art in this region in general is very, very new, and I believe it is important to start somewhere, with something, even if it’s not perfect.

Kader Attia: For me, it’s also fine. I think it’s another step, as Wael says. I was in Doha for the opening of the Museum of Islamic Art in 2008, and I think they did well. What I like very much is that they are doing it step by step. They have built this beautiful museum designed by IM Pei, and they have the collection. Even if the works have been seen before, this new dynamism is now visible. But to answer your question, I think all artworks, mine or those of other artists from any background, are at home in any museum of the world.

Scale model of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Abu Dhabi

Courtesy Gehry Partners, LLP. Photo: Tarik Iles

Artist’s rendering of the exterior of Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Qatar

Courtesy Nafas Art Magazine, Berlin

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie: How would you compare the Gulf museum projects with the Modern Art Museum of Algeria (MAMA), which opened in 2007?

Kader Attia: I support the MAMA. Algeria has a lot of problems with fundamentalists, especially in the south now, and it’s a country that only recently came out of a civil war. The fact that the government invested money in culture is very important. It’s more than a sign, it’s real. When the MAMA opened, it was amazing to see the people who came. There was a great sense of energy. I think the director, Mohammed Djehiche, is very open minded and is really aware of how difficult it is today to show contemporary art in a country like Algeria. My involvement with the museum is not just as an artist; I’ve also been asked to propose curatorial projects. Nevertheless, in relation to what I said earlier about the tight space available for criticism of the political system in Arab countries, I think showing political contemporary art in the MAMA is going to be a difficult job for everyone. Let’s see…

Vasif Kortun: At Platform, we have developed an active resentment against projects that put forward this kind of representational politics. I try to dissuade artists from participating in such projects. I am not sure if an artist’s work is at home everywhere. Also, I don’t see any museums in the Western hemisphere destabilising their narrative. I don’t see any creating situations where there is a serious openness to artists that come from other places, unless those artists are used to perform certain premeditated roles for the collection. I think that the acquisition policies of such institutions are still very much about buttressing the narrative and working with a very limited stable of galleries. So a project such as Mathaf – which has a very, very impressive collection – seems more like home to me. If I were an artist, then I would feel very much at home there, because there is space for me, there is room for me, and it is possible to interact with a different kind of narrative for me.

Dia Al-Azzawi

Folklore Mythology 1968

Oil on canvas

58.1 x 181.3 cm

Courtesy Mathaf, Arab Museum of Modern Art © Dia Al-Azzawi

Ahmed Basiony

Performing Symmetrical System at Mawlawiyah Palace, Cairo, 2009

Courtesy Nafas Art Magazine, Berlin © Estate of Ahmed Basiony

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie:All of you are involved in the running of art spaces in your respective cities. Why, in addition to your work as artists or curators, are you doing this? Are these spaces responding to specific needs that you’ve identified as crucial in the art scenes of Istanbul, Alexandria and Algiers?

Vasif Kortun: We are just shifting from a contemporary art institution, Platform, which had a basic library and an archive and a residency programme and an exhibition space, to a larger institution, SALT, which is much more based on research, archives and intellectual production. We are moving into publishing, which we had not done before in any serious way. We are moving away from contemporary art as a privileged medium. This also has to do with the fact that we are expanding with and utilising the experience of two other institutions – the Garanti Galeri, which is about urbanism and architecture, and the Ottoman Bank Research and Archives, which is about social and economic history – so it is inevitable that we move on, but we are trying to move to an interdisciplinary format, where questions of medium and discipline are not our primary concern.

Walid Raad

Let's be Honest, the weather helped (plat 008 Finland) – Detail 1998/2006–7

Lightjet print

48.8 x 72.4 cm

Courtesy Anthony Reynolds Gallery, London © Walid Raad

Jeffar Khaldi

From Fade Away 2010

Oil on canvas. Series of one diptych and four paintings

Dimensions variable

Courtesy Mathaf, Arab Museum of Modern Art © Jeffar Khaldi

Wael Shawky: MASS Alexandria opened recently. Originally, it was my studio, but I decided to divide it into eight studios for eight students. Each will have his or her space for six months, during which time they will host professionals, artists and curators, and organise workshops, seminars and talks. I felt this was the only way to create something parallel to the University of Alexandria’s art faculty, because it has a lot of problems. It’s extremely conservative and academic. The idea is for MASS Alexandria to create a channel for students to gain exposure to contemporary art. Alexandria is my home town. I graduated from the university. Every year, more than 500 students graduate from the art faculty. Yet we still don’t have a contemporary art scene. Somehow, I knew that opening MASS Alexandria wasn’t my responsibility, that it wasn’t up to me to make this space alive. But I was pushed to do it. I always talked about it, and I always said this must happen, we need to have this space in Alexandria. I never thought I would do it. But somehow everyone was just waiting for me to do it.

Kader Attia: We, the artist Zineb Sedira and I, have been working on our space for two years now. We are scheduled to open with an exhibition in the next year. The idea of this project, which will be named ‘Art in Algiers’, is to use both the geographical and historical situations of the country as a bridge linking the culture of Africa to the Arab world. It’s an Afro-Arab project. We’ll be inviting artists, curators, philosophers and critics – many different sorts of intellectuals from all over the world – to come to Algiers to give lectures and share their knowledge with Algerian people, because many of our art students are not allowed to travel to Western countries. They won’t get a visa for the West, but they will for the rest of Africa and Arab countries. We want to create an agora to gather people from all over the world with this idea of discovering each other and sharing Afro-Arab culture. It is something I’ve wanted to do for many years, because I grew up between Algeria and France. I have both French and Algerian nationalities and passports, but I always felt the huge gap between the West and the East. I want to fill that gap. And maybe in the end it will become a bookshop, because in the beginning the nature of the project was more editorial. The aim was to produce publications, because it is difficult, technically and politically, to publish books or reviews in Algeria. But I need to think about it. It’s also just about opening something in the country where I’m from, and where all my family lives. It’s not a sort of militant project, but it’s the idea that you can improve your country by yourself, even if it is on a small scale. If you can improve the corner of your street, that’s the beginning of something – that’s progress.