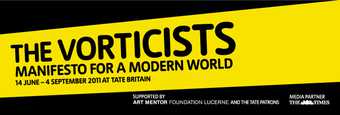

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Torpedo Fish (Ornement Torpille) 1914

Cut bronze

15.6 x 3.9 x 3.3 cm

Courtesy Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach

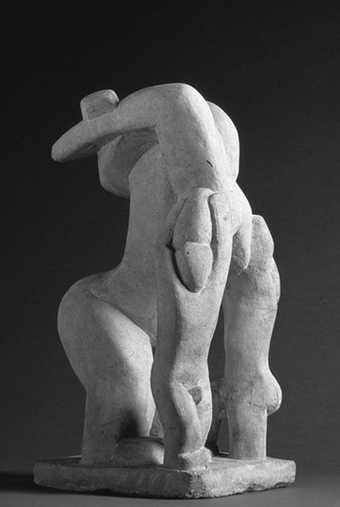

The month of June 1915 witnessed two important events in the history of Vorticism: the opening on 10 June of the Vorticists’ first retrospective exhibition, held at London’s Doré Galleries in New Bond Street, and the tragic death of their chief sculptor, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, in the trenches of Neuville Saint-Vaast on 5 June. Gaudier’s death at the age of 23 inspired fellow Vorticist Ezra Pound to publish a book-length memoir of his close friend in 1916, in which he declared that “a great spirit has been among us, and a great artist is gone”.1

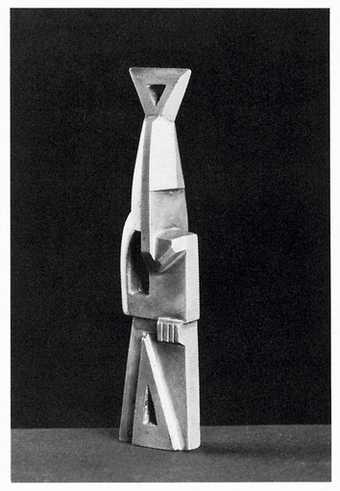

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Caritas 1914

Portland stone

Courtesy Musée des Beaux Arts d'Orleans

The sculptor’s posthumous reputation was such that The Leicester Galleries mounted a memorial exhibition of 45 of his works in May and June 1918, a little over a year after the same gallery hosted the first retrospective of his mentor, Jacob Epstein. Such acclaim is all the more remarkable when one considers the fact that Gaudier arrived in England from France in January 1911 as a virtually penniless, untrained artist with no contacts among the London avant-garde. His introduction to cultural circles in the metropolis only developed a year later when he befriended the art critic Haldane Macfall, and over the course of 1912–13 his circle of acquaintances expanded quickly to include the group of Fauves associated with the journal Rhythm 1911–13, the sculptor Jacob Epstein, Roger Fry and the Bloomsbury circle and the poet Ezra Pound.

Despite his limited resources, he produced more than 100 sculptures from 1910 to 1914 and hundreds of drawings.2 In his preface for the memorial exhibition, Pound highlighted the poignancy of a life cut tragically short, writing that ‘the volume and scope of the work is, for so young a man, wholly amazing’, and that his untimely death was ‘the gravest individual loss’ the arts sustained during the war.3 Pound’s bereavement was particularly acute because of his close collaboration with Gaudier in developing a theory of Vorticist sculpture. Following their initial encounter in July 1913, they joined the circle of anarcho-individualists associated with the journal The New Freewoman (1913), soon to be re-christened The Egoist (January 1914–December 1919), thus defining a radical political orientation within the Vorticist movement.

It was in The Egoist that Pound’s first pronouncement on Gaudier-Brzeska’s sculpture appeared, as well as the latter’s own initial forays into art criticism. Relations with The Egoist remained strong during the period leading to the official launch of Vorticism in the summer of 1914: the impending publication of the Vorticists’ journal BLAST was repeatedly announced in The Egoist from April onwards, and when BLAST 1 finally appeared in early July, The Egoist was prominently advertised there in the same bold typeface as the journal’s manifestos. Central to Gaudier and Pound’s vision of Vorticist sculpture were the metaphoric association of direct carving with the anarchist politics of direct action; the correlation between human sexuality and The Egoist’s founder Dora Marsden’s concept of the embodied, ‘desiring’ ego; and their allegiance to primitivism in opposition to European classicism.4 Gaudier’s championing of direct carving, and the virility needed to carve into hard substances, was underscored in the 1915 ‘First Vorticist Exhibition’ at the Doré Galleries, where he showed eight sculptures, all made from stone.5 This choice was significant, as Gaudier, despite his (and Pound’s) public outcry against sculpting in plaster, continued to do so, as evidenced by his plaster Bird Swallowing a Fish, revealed at the Allied Artists Association exhibition in June 1914.6 Gaudier and his colleagues evidently saw the 1915 show as something of a retrospective for his experiments in direct carving: the variety of materials employed in his works on display ranged from hard Derby stone and Red Mansfield stone to colourful alabaster and green Irish marble. The earliest sculptures on view were his melancholy Singer and exuberant Red Stone Dancer, both dated 1913; large-scale works from 1914 included his figurative Caritas and Boy with Coney; and among a series of hand-held sculptures were Small Fawn and Green Stone Charm. In The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World, we have included a representative selection of these and related works, which underscore the variety of materials, styles and subjects that served to define Gaudier’s Vorticist output.7 These included two examples of his hand-held sculptures carved in metal: his famous cut bronze Ornament Torpille, known as Torpedo Fish (1914), commissioned by the critic and champion of Vorticism T.E. Hulme, and his delightful Fish 1914 in chiselled bronze, recently acquired by Tate and once owned by Hulme’s lover Ethel Kibblewhite.8 Both works were like small-scale totems for their owners: Hulme routinely visited acquaintances with his Ornament Torpille in hand, playing with it during conversations, while Kibblewhite carried her Fish in her handbag at Gaudier’s suggestion. The artist himself highlighted the talismanic aspect of his Green Stone Charm by wearing the sculpted relief around his neck in imitation of New Zealand Maoris. The status of these works as charms or talismanic fetishes not only underscored their creator’s embrace of primitivism, but his radical conception of the function of modern sculpture as wholly outside the classical tradition.Silber, op. cit., p.95, and Jon Wood, ‘Ornaments, Talismans and Toys: The Hand-held Sculptures of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’, in Blasting the Future: Vorticism in Britain, 1910–1920 (London, 2004), pp.41–8.

Front cover of BLAST II, July 1915

29.8 x 24.8 cm

Courtesy The Poetry Collection, University at Buffalo, State University at New York

Thanks to the recent acquisition by Tate of a series of his sketchbooks, we can also gain insight into Gaudier’s working method in developing his sculpture. The four books were originally owned by Ezra Pound: three date from 1910–12, the period before he met the poet, but one dates from autumn 1913 to July 1914, when Gaudier was fully launched on his Vorticist phase. Known as the Chenil Sketchbook (purchased from ‘Charles Chenil and Co of 183a King’s Road Chelsea’), it contains 86 unnumbered pages with pencil drawings throughout, many relating to specific sculptures. As Evelyn Silber has noted, the sketchbook probably contained many more drawings, for the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Orléans owns a series closely related to the Chenil drawings all measuring 20–20.5 x 12.5 cm, the same dimensions as the Chenil Sketchbook.9 The last page of the sketchbook bears an imprint identifying it as a ‘Chenil Blue Book’ purchased from ‘Charles Chenil and Co. of 183a King’s Road Chelsea’. This label indicates that Gaudier acquired it at the Chenil Gallery and artists’ shop located next to the Chelsea Town Hall in London, on the original site of the old Chelsea Arts Club. Founded in 1905 as a Bohemian alternative to the more established galleries on Bond Street, the Chenil was the brainchild of Jack Knewstub, an avid promoter of Augustus John, William Orpen and those artists associated with the New English Art Club. Vorticist William Roberts later recalled that the shop was dominated by John, whose works were permanently on view; moreover in an attempt to keep apace of avant-garde developments, the Chenil staged David Bomberg’s first one-person show in July 1914, exhibiting his newest work Mud Bath outside the gallery in an audacious gesture of public advertising. Owing to John’s overweening presence at the Chenil, Wyndham Lewis saw fit to ‘Blast’ the gallery in the Vorticists’ opening manifesto published in BLAST 1.10

While the scope of this article forbids a detailed analysis of the sketchbook’s contents, I will address the subject matter chosen by Gaudier and point to specific drawings with a direct bearing on his sculptural production.11

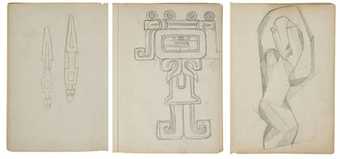

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Chenil Sketchbook c.1913

Normal

0

MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

–14.

Three pages: Sketches for Ornament (Toothbrush) (sheet 23), sketch after the Temple of the Serpent (56), sketch for Red Stone Dancer (77)

All images courtesy Tate Archive

Thanks to the recent acquisition by Tate of a series of his sketchbooks, we can also gain insight into Gaudier’s working method in developing his sculpture. The four books were originally owned by Ezra Pound: three date from 1910–12, the period before he met the poet, but one dates from autumn 1913 to July 1914, when Gaudier was fully launched on his Vorticist phase. Known as the Chenil Sketchbook (purchased from ‘Charles Chenil and Co of 183a King’s Road Chelsea’), it contains 86 unnumbered pages with pencil drawings throughout, many relating to specific sculptures.

Of the legible sketches, 24 relate to Gaudier’s small-scale ornaments or toys, his decorative projects for the Omega Workshops, or his larger figurative sculptures, such as Red Stone Dancer and Birds Erect 1914; 32 are studies of fish, such as pike, with varying degrees of abstraction, or of animals – both domestic and exotic – with many evidently drawn at London Zoo; and eleven are purely abstract studies, including those of geometric patterns possibly derived from Polynesian, Mayan, or Aztec sculpture in the British Museum, or copied from book illustrations (for example, sheets 3, 47–49, 52 and 53–56).12 The one on sheet 56 depicts a section of the pre-Columbian Temple of the Serpent in Xochicalo, Mexico, dated 650CE. Of the drawings in the first category, a number are studies for specific works: the three on sheet 50 relate to Ornement Torpille; another series combines geometric motifs derived from Ornement Torpille and Red Stone Dancer into figural abstractions (67, 71, 73 and 75); and a third cluster comprises composite variations on his hand-held sculptures, such as his bronze Fish (see page 72 for details), brass Toy and marble Duck, all of 1914 (57 and 81). Three elaborate drawings on a sheet datable to 1914 combine the triangular shape of Fish with that of a bird’s head, possibly derived from his study of totemic sculpture of the Pacific Northwest (British Columbia) (57). Another sketch on sheet 23 of an abstracted, humanoid figure closely resembles his Ornement (1914) carved in bone. Sheet 76 has a preliminary drawing for Birds Erect that bears a close resemblance to a related study now at the Pompidou Centre in Paris.13 The sketch on sheet 1 is clearly of Amedeo Modigliani’s sculpted Head 1911–12, exhibited at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in May–June 1914, where Gaudier showed six works.14 A series of drawings of a copulating couple (10 and 14) are an erotic variation of studies done for his mahogany Round Tray, created in late 1913 for Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops.15 Gaudier’s drawings of animals and fish attest to his status as an accomplished animalier. His observant sketches of a wallaby (5, 6 and 7), greyhound (11), cat (17), frog (24), penguin (28), heron (29 and 30), vulture (43 and 45), swan (59), deer (63) and alpaca (65) capture the anatomy and spirit of these creatures through a masterful combination of simple lines and geometric shapes.

The drawings for Red Stone Dancer, Ornament Torpille and of an elegant greyhound are especially revelatory of Gaudier’s evolving style and subject matter during his Vorticist phase. The portrait of a greyhound at rest (sheet 11) is a wonderful example of Vorticist abstraction, wherein the animal’s sleek body is regularised and reduced to geometric forms that nevertheless convey an accurate rendering of its natural appearance. The artist captures the greyhound’s peculiar posture, with its hips held above the floor by its powerful haunches. The deep barrel chest and slim waist have been refashioned into a straight line from the point where the chest touches the floor to its intersection with the stomach and hind legs. He extends the long tail, tucked between the legs, to form a circle defining the dog’s rear anatomy as a counterpart to the triangulation of other parts of its body.

This drawing – so reminiscent of the sculpted Dachshund 1914 – attests to Gaudier’s powers as an empathetic animalier who adapted his long-standing interest in animals as a metaphor for anarchist naturism (but also our innate potential for violence)16 to his emerging Vorticist vocabulary, informed by the work of his avant-garde heroes Constantin Brancusi and Epstein.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Red Stone Dancer (c.1913)

Tate

Meanwhile, the preliminary drawing for Red Stone Dancer on sheet 77 is an easily recognisable figure of a dancing woman with arms wrapped around her head and a raised right breast. The posture and bodily proportions are strongly reminiscent of West African sculpture from the former French Congo, such as that of the Teke or Baga.17 The use of cross-hatching not only serves to create a rhythmic play of volumes and shadows, but to facet form using a Cubist vocabulary found in related drawings from late 1913.18 The sketches on sheet 50 imagine his Ornament Torpille from three different viewpoints, registering Gaudier’s careful planning in developing the complex combination of geometric forms and perforated voids that constitute this small sculpture, cut from bronze. The preliminary drawings have a humanoid appearance, composed of an inverted, pyramidal shaped head, conical breasts and parted legs forming an upright triangle. This feminine form takes on added significance when we measure the English language title, Torpedo Fish, against the artist’s original designation, ‘Ornament Torpille!’19 The title Torpedo Fish has led historians to posit widely divergent and contradictory readings of the work: I would argue that the French phrase alternatively provides us with the key to its actual meaning. In fin-de-siècle Parisian slang, torpille referred to “a woman of lax morals”,20 and the phrase torpille d’occasion even more crudely to an ambulatory prostitute; thus, Gaudier’s actual title – with its provocative exclamation mark – urges our perception of this geometric figure as a sexualised and available woman, positioned in an assertive stance, with one hand on her hip. The term ornament in turn may simultaneously allude to the sculpture’s status as a carved ornament and to the female subject’s self-“ornamentation”. Such a reading is totally in keeping with the irreverent celebration of male and female sexuality found throughout Gaudier’s work and of a piece with the anarchist notion of sexual liberation promoted in The Egoist, making the work a suitable talisman for the sexually active Hulme.21

Taken together, the drawings in the Chenil Sketchbook provide us with a remarkable record of Gaudier’s protean imagination, his skills as a draughtsman and his unique contribution to Vorticist aesthetics.