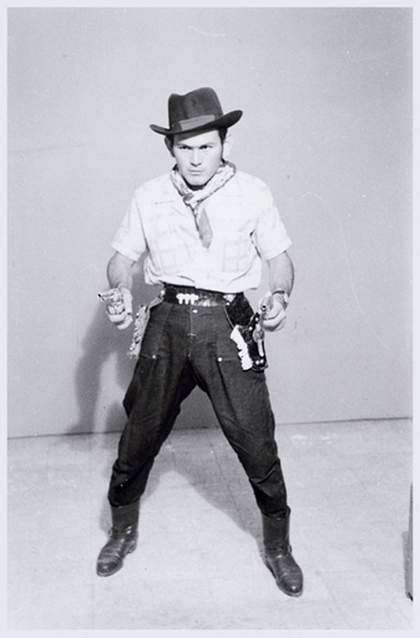

From its birth in the early nineteenth century, photography has been used to document the world – to offer an accurate image of a person, place or thing. And long before the term documentary photography came into common usage (and there is still debate around the moment of its invention), photographers used the notion of the camera’s relationship to reality to explain their practices as image-makers. Eugène Atget, for example, a pioneer of urban street photography at the turn of the last century, is known to have described his eerie, atmospheric pictures of depopulated Paris streets, shop-front window displays and deserted parks as “simply documents that I make”. However, Atget’s notion of the photograph as a document, a word with its own connotations, reminds us that it is possible to produce photographs that can be read or used in multiple, even contradictory ways. Akram Zaatari’s project Objects of Study, for example, takes the commercial studio portraiture of Hashem el Madani, made in Beirut from the 1950s to the 1970s, and transforms the original purpose of each individual image by bringing them together. Portraits paid for by the sitters and destined for the walls and sideboards of family homes are assembled so that collectively they form an archive with a broader social and political significance.

Akram Zaatari

Anonymous. Studio Shehrazade, Saida, Lebanon, 1960. Hashem el Madani 2007

Photograph on paper

29 x 19 cm

© Akram Zaatari

Documentary form, however, is about more than simply the use-value of an image, or group of images. It also relates to the ways in which the camera bears witness to the world, and, therefore, inevitably raises questions about history and social commentary. Several of the projects included in New Documentary Forms concern politics at the global level: environmental issues in Mitch Epstein’s American Power; political upheaval in Guy Tillim’s Congo Democratic; and the on-going conflicts in Afghanistan and the Middle East in works from Luc Delahaye’s series History.

Each of these contemporary artists is engaged with the kinds of subjects that we might expect to see photographed in newspapers or magazines, and yet their work is produced in such a way that it rightly claims the museum or gallery wall as its proper place. This reaching across contexts, from page or screen to picture frame, has much to do with the formal languages of representation evoked: the large-scale tableau format that Delahaye uses for his images of conflict and its effects, for example, relates as much to nineteenth-century history painting as any journalistic photographic tradition. And, likewise, writing about his work Red, Boris Mikhailov describes the overwhelming impact of that colour within early Soviet visual culture: from the red army, to the red flag, to the graphic use of red in Russian constructivist art. Consequently, in his photographs of everyday life in Soviet Ukraine that make up Red, the colour is everywhere, from giant flags in parades and at events, to the smallest details of figures and interiors, as though the whole society was infused with this recurrent symbol. In his later series At Dusk, which documents the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Mikhailov again offers his own personal, poetic account of the real world, this time handstaining his black-and-white photographs with an inky blue dye, so that the Ukraine seems to exist in a perpetual twilight.

While some artists, such as Mikhailov and Zaatari, attend carefully to the rhetorical presentation of photographs through archiving, post-production and installation, for others it is vital to consider the approaches taken in making the images in the first place. Delahaye and Epstein use large-format cameras that register incredible levels of detail, maintaining great evenness across the picture plane, and resulting in a very different visual language from that of the photo-journalistic “snapshot”. These deliberate, formal approaches seem to suggest that what contemporary visual culture lacks are images of political and social consequence that can bear a sustained look: that what the internet and 24-hour rolling news contributes in terms of the immediacy and quantity of images, it lacks in providing objects of consideration and reflection. The photography brought together in New Documentary Forms asks us to spend time with images of events and their consequences; to reflect carefully on subjects that perhaps we are accustomed to seeing only fleetingly, and understanding superficially, before moving on.

Boris Mikhailov on At Dusk 1996

Boris Mikhailov

Untitled, from the series At Dusk 1993

Toned gelatin-silver print

29 x 11 cm

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin © Boris Mikhailov

Sentimental explanation

“Every generation has its war.”

(Folk wisdom)

1941. I was three years old and I can still remember the bombings, the howling sirens and the searchlights in the wonderful, dark-blue sky. Blue, blue, light-blue… For some reason we think that one generation will be spared a war. I see this blue series as the second. The population of the city has shrunk to 250,000 inhabitants. Fifty to eighty per cent of the factories and plants have shut down. More people are dying than being born. For a long time the dead were buried in polyethylene bags. You have to bring your own sheets, syringes, medicine, etc with you to the maternity home. The rats are the first to leave the sinking ship. These little animals… Everybody knows that the old people have to die first… My son Iljuscha has been living in another country for three years. Thirty people have frozen to death on the streets. This prompted my friend to open an exhibition. Homes were not heated for three long winter months at minus 22 degrees. A nineteen-year-old girl stole my shoes in the train. Having woken up by chance, I caught up with her bare-foot at the end of the carriage. Perhaps I should emigrate and live with the French? The door to my relatives’ home was broken down and their home was burgled. You are scared to enter a dark hallway. The bank does not return the money. Everything stinks of urine. But an acquaintance of mine, a photographer, has opened a restaurant and sold his camera. Another breeds dogs. A third heals people.

1994–5. People earn four times as much, the average salary is now around $50. But it has not been paid for months. Prices rise. They are almost as high as in New York or Berlin. There are more and more shops with Western goods. There are people who shop there. Is it perhaps a good thing that fewer people will live here in future? But more Chinese people? “Everything will turn out fine,” the radio broadcaster says today. I have forgotten something. The sewerage system stopped working in the summer. Soldiers watch out that nobody bathes in the river. Many people have diarrhoea, but cholera has not broken out. We are pleasantly surprised that tumbledown houses in the city centre are being renovated. Pregnant women often find it difficult to cross the road because of heavy traffic. I have already seen a picture for the new pink book, at dawn: A woman held up her new-born son by the foot, then lifted it up above her head, and he suddenly looked like a Buddha. The woman kissed him.

A new life has been born.

Mitch Epstein on American Power 2003–present

Mitch Epstein

Ocean Warwick Oil Platform, Dauphine Island, Alabama 2005

Photograph

178 x 228 cm

© Mitch Epstein

When I made the first pictures for American Power in 2003 on commission for the New York Times, I had no idea that a five-year project would emerge from it. I was sent to photograph the disappearance of the town of Cheshire, Ohio, after it had been bought out by American Electric Power. The 200 or so residents had been complaining of health problems due to contamination from the local AEP coal plant. Nearly everyone took the company’s money to leave and never bring a lawsuit against it in the future. I saw houses getting razed in a matter of minutes and homeowners wandering around the ruins of their former life looking for something to salvage. Later, back in New York, I kept thinking about the erasure of Cheshire. I also thought about the paranoia and corporatism that was fuelling a new American censorship: while shooting there, I’d been told by law enforcement that I was not allowed to point my camera at infrastructure any longer, even from a distance.

Five years later, I had travelled to 25 states with my large-format camera on a visual investigation of how energy production and consumption influenced the American landscape and culture. I wanted to engage with the idea of American-ness in the new millennium. I had no political agenda. I began with a rule: in every picture there had to be a direct relationship to energy. But I allowed myself a flexible interpretation of the rule. For example, I made a Hurricane Katrina series and photographed an electric chair, as well as the 2008 Republican Convention, I like having structure, but avoid being rigid. Working with a large-format camera enabled me to make pictures that are formally layered and conceptually complex.

Tate Modern New Displays II - A recently acquired installation by the Korean-born artist Do Ho Suh and a two-channel slide projection work by the Polish artist duo KwieKulik

Do Ho Suh on Staircase – III 2009

Film still of Do Ho Sugh (left) installing Staircase – III at Tate Modern, March 2011

Courtesy Tate Shots © Do Ho Suh

Early one morning in 2001, around 4am, I was measuring the corridor outside my small New York studio apartment. I wanted to turn the space into a 1:1 fabric piece. I chose that time of the day because I was afraid Arthur could otherwise come down to my floor and discover me doing something strange. I was on all fours measuring every architectural detail, when I looked up and saw Arthur. He had arrived via an enclosed staircase and was looking at me curiously. He was an early bird.

Arthur Henoch, my landlord, was very supportive and sympathetic to me as a struggling young artist, but the door to his staircase was always locked. I tried to explain what I was doing, but I don’t think he understood me until he saw the corridor piece at my show a couple of years later.

This early morning exchange was a great ice-breaker, as we then became good friends. I have been living in the half basement of this four-storey brownstone house in Chelsea since graduating in 1997. Only after six years did I finally feel comfortable asking Arthur to allow me to enter his personal space to measure the staircase.

Staircase – III is a fabric version of the hidden staircase that connects the floor where I live to Arthur’s home. As an artist, I have always been interested in transitional spaces – such as corridors, bridges and gates. They are not destinations, but are used to go somewhere else. This staircase is another in-between space that connects and separates two personal spaces: mine with my friend Arthur’s.

Maxa Zoller on KwieKulik

KwieKulick

Details of Variants of Red/The Path of Edward Gierek 1971

Two-channel slide porjection

© Zofia Kulik

My first visit to Zofia Kulik’s house just outside Warsaw was a life-changing experience. I was deeply impressed by the sheer abundance of her artistic archive. Since forming the collective KwieKulik in the late 1960s, Kulik and her then artistic partner Przemyslaw Kwiek have been collecting tens of thousands of slides, photographs, objects and text material. The slides, all of which are in perfect order and neatly filed in endless rows of shelves, are documents of the artists’ strange and surreal interventions in public and domestic spaces: there are photographs of bright yellow crêpe paper balls on the streets of Warsaw, red flags on the grass, a beautiful circle of lush oranges on the floor of the couple’s apartment.

These practices changed when Poland entered a new political era with the appointment of Edward Gierek as First Secretary of the Communist Party. In 1971 KwieKulik made a double slide projection called Variants of Red/The Path of Edward Gierek, which placed their work within the nation’s more open political utopia: the colour red symbolised Gierek’s brand of socialism. In the mid-1970s their work became more personal. I was particularly struck by a series of photographs entitled Activities with Dobromierz 1972–4, in which KwieKulik placed their new baby son in a bucket surrounded by a circle of crisp apples. In another picture this cute little cherub lies on the floor in the living room inside a square made from fresh sausages. Yet another image shows the baby standing up in a cardboard box amid a sea of onions.

Zofia passionately and patiently explains to me that in Poland in the 1970s, a time when socialism was still competing with capitalism, the object was not seen as a mere commodity representing financial value, but as a concrete three-dimensional structure in space that related intimately to the human body. If we could only think of objects and things not in terms of their use value, but as relational elements that express and order our world and our bodies, our desires, fantasies and fears, Zofia continues, then we would be able to see our immediate everyday realities as flexible, fluid, energetic fields – and we could act in them more freely and creatively.