Is there any way I can get hold of a whale skeleton in Mexico? And can you help me to assemble it? The call came from Gabriel Orozco. I said yes to both because I am also crazy. In order to do this, Gabriel and I organised a team of advisers, technicians and artists. Four scientists were involved in the project. One of them, a biologist, was responsible for organising the incredible journey of exploration to Isla Arena in the bay of Guerrero Negro, on the Pacific coast of Baja California in north-west Mexico. A physical anthropologist technician and a palaeontologist advised us on the anatomy and osteological treatment. Pierre-Yves Gagnier, another palaeontologist and director of collections at the Natural History Museum in Paris at that time, sent us very helpful information.

Gabriel Orozco

Whale in the Sand 2006

C-type print

40.6 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © Gabriel Orozco

We set out at dawn on 6 February 2006 for Isla Arena (Sand Island), where it seems we will be able to find an enormous specimen, beached for just the right amount of time: still as complete as possible, and requiring the least amount of preparation. It is the first time either Gabriel or I have been to this area, and the light of day reveals one of the most striking landscapes on the vast peninsula of the Baja. The sand dunes, which make up the greater part of the island and give it its name, form the backdrop to the scene. It is part of El Vizcaíno biosphere reserve, which, in addition to protecting the desert of the same name, constitutes a sanctuary for the grey whale (Eschrichtius robustus). In the bays of the reserve, they mate, give birth and raise their young: some of them are beached and die there. When we arrived we could see vertebrae projecting from the sand of the dunes or beach, indicating skeletons possibly worth investigating, but these included the bones of birds, turtles, dolphins and sea lions, alongside masts, countless bottles (some of them dating as far back as the end of the nineteenth century), life vests, fishing nets, massive ships’ cables, bulbs and workmen’s helmets cast ashore by the ocean currents. Nothing but water on one side, nothing but sand on the other. It is here that we found our specimen. We walked up to the skeleton, gazing at it in silence as we calculated the many hours of work that awaited us, and wondered where to begin.

In order to salvage it, a certain procedure had to be followed and special tools were needed: shovels, saws, different kinds of knives, rope, labels. The first task was to get rid of as much as possible of the skin – a thick, coarse hide – that still covered 70 per cent of the whale’s body. We then separated and sorted out the bones.

Gabriel Orozco with whale skeleton, Isla Arena, Baja, California (2006)

Courtesy Marco Barrera Bassols

In this way we discovered the atlas and the axis (which join the skull to the cervical bones), and some of the bones of the right fin, from the side of the skeleton that had been most exposed. We also found a series of five cervical bones fused together, and calculated that our specimen had died at around the age of 30 (40 years is the average life-span for this type of whale) and had weighed approximately 30 tons. The same biologist who helped us in our search collaborated in another task: the transport of the skeletal remains from Isla Arena – on what would be the whale’s last ocean voyage – to Guerrero Negro, where the fat and organic remains we had been unable to take off on the beach were removed. Accumulated fat comprises 60 per cent of a living whale’s body: they feed for four or five months and then live on their fat, which allows them to endure the cold temperatures of the waters in which they swim. Even their bones consist of at least 30 per cent fat. To remove the organic surface we erected a makeshift greenhouse and let the bacteria do the work.

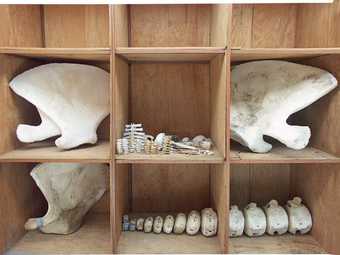

Bones from the whale skeleton found by Marco Barrera Bassols and Gabriel Orozco ready for transportation to Mexico City

Courtesy Marco Barrera Bassols

The skeleton was then shipped from Baja California Sur to the Buenavista railway station in Mexico City, where an improvised workshop had been set up. As Gabriel was deciding how to create his work, some of the bones were restored, while others that we had been unable to find were reproduced. Each one was carefully catalogued. The skull and jawbones, the axis and the atlas, the cervical, lumbar and dorsal vertebrae, the ribcage, the pelvic bones and those of the fins were measured and photographed, in what we hoped would result in the first complete cataloguing of a grey whale in Mexico. This was made possible by the expert advice of specialists in anatomy and osteology. Once the bones had been assembled on a new steel structure, the skeleton measured 11.7 metres (38.4 ft) along its curvature, weighed 1,169 kilograms and consisted of 169 bones, with only one of the tympanums missing. At the same time, research was done on the many different ways in which skeletons of marine mammals have been assembled and suspended in various natural history museums – with advice from specialists and institutions having recent experience in similar undertakings.

Gabriel Orozco inspecting the skeleton in Buenavista Station, Mexico City

Courtesy Marco Barrera Bassols

Gabriel analysed the structure of the skeleton, getting to know each of its parts, one by one. He took some other pieces, which he brought along with the skeleton, trying out various lines with a pencil. It was not the first time he had drawn on a bony surface, so neither the porosity, the hardness, nor the geometry was alien to him. Given the size of the skeleton, a study also had to be made of the volumes, such as the ribcage and the fins, which the individual pieces were unable to provide. Photographs of other skeletons of the same species, mounted in a way similar to that chosen for Mobile Matrix (Mátrix Móvil), served as a basis to generate other lines, and as those pieces took shape, Gabriel began to work on a vertebra, which also helped him to decide on the thickness of the line finally to be used on the entire whale skeleton. At every stage he took digital photographs, printed out daily so that he could visualise the progress made and the solutions he was finding.

Cleaned whale bones in the temporary workshop at Buenavista Station, Mexico City 2006

First graphite drawings on the whale spine in the workshop at Buenavista Station, Mexico City 2006

From that moment on until the day before the final installation, volunteers began to join the process unfolding in the great hall of the train station, including the job of drawing with pencils on to the skeleton. It took twelve people working for six weeks using 6,000 pencils. How the piece was to be installed in the José Vasconcelos Library in Mexico City depended on various factors: the many viewpoints from which the public would be able to observe it; the characteristics of the grid formed by the suspended bookshelves; the two stairways connecting the ground floor with the first mezzanine level; and the natural and artificial lighting conditions. The piece was suspended three metres above floor level. The last days of installation were dramatic. We used special wagons to transport sections from the station to the interior of the library, and with scaffolding and winches, suspended it in place in the centre of the great nave. Engineers and workers, librarians and groups of guests invited to the inaugural ceremony approached and stood around us, observing our efforts. Their applause brought us to the final realisation: at 10.30 on 16 May, Mobile Matrix lay there floating in space, still swaying slightly back and forth.