It is a little-known fact of art history that the watercolourist Francis Towne (1739–1816) killed the watercolourist Eric Ravilious (1903–1942).

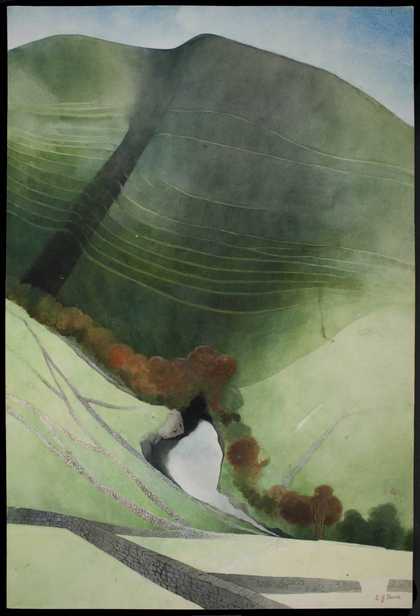

Towne was a landscape artist who had an affinity for open spaces, wild scenery and ruins. A conventional repertoire of subjects, then, for a Romantic topographer. But Towne’s style, at least in his uncommissioned work, was quite different from that of his peers. Working with a lightly loaded brush and an ascetic colour range, he approached wild landscapes as abstract compositions, to be parsed principally for their pure design. The Source of the Arveyron 1781, for instance, is landscape almost as transparency. The mountains exist as graceful bulks or hulls, shucked of their close details, surviving only as monochrome wash. The Chamonix valley is reduced to an intersection of tilted stripes: sky, cloud, peak, ridge, shoulder, arête, glacier, ice-pinnacles, glacier again, all tipping the eye downwards to the outflow of blue meltwater that curls from the snout of the Mer de Glace, and begins its descent to the Arve, the Rhone and the Mediterranean.

As Peter Davidson records in his brilliant book The Idea of North (2005), Eric Ravilious was from his student days fascinated by Towne. He collected Towne’s work as part of his ongoing obsession with ice and the far north (he also gathered Arctic exploration narratives, images of the Inuit and whale hunts and engravings of maps), and his scrapbooks included a black-and-white photograph of Towne’s Arveyron, the work that interested him most. Sparseness and spareness were what Towne taught Ravilious in terms of technique. Like Towne – and like Edward Burra after him, late in his career – Ravilious instinctively read landscapes for their flattened existence as line and plane.

Ravilious was brought up in Eastbourne, at the foot of the South Downs, and before he fell in love with the ice of high altitudes and high latitudes, he loved the chalk of the south. With its soft and equalising sunlight, its Neolithic trackways and its loneliness, chalk primed his imagination. The Downs, he wrote once, shaped “my whole outlook and way of painting… because the colour of the landscape was so lovely, and the design so beautifully obvious”. Under the influence of both Towne and Downs, he grew to cherish certain characteristics of place: crisp flowing lines, an aura of lambent remoteness, a detachment from the lived world, a combination of human presence and extreme age.

Thus, for instance, The Vale of the White Horse, with its rearing foreground and Möbius-like looping lines, is an image in which the influence of Towne is unmistakable. Ravilious painted it in 1939, and it records the interference patterns of ancient history and imminent war. The Bronze Age horse gallops over the hill, but the foreground colours invoke camouflage, and the cross-hatched sky (a Ravilious insignia) suggests searchlights drilling their beams up and through the air. As Towne’s painting gestures to a river that runs away, so Ravilious’s is haunted by action occurring elsewhere, off-stage.

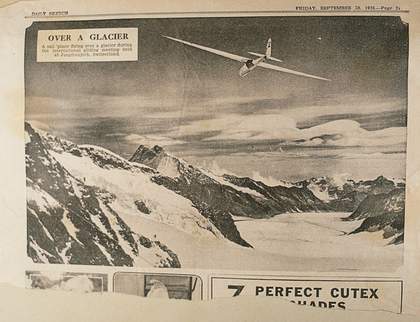

Newspaper cutting in Eric Ravilious's scrapbook (c.1937)

Photo: Tate Photography

For most of Ravilious’s life, the Downs answered his landscape needs. Especially in winter – when the beech hangars stood out like ink strokes in a Chinese watercolour – they embodied his aesthetic ideal: crisp lines, the fall of pale light on pale land. But as the 1930s wore on, he began to desire and dream of travelling north, to the ice and snow of the Arctic circle.

By the time the war began, he was restless to travel, hungry to swap chalk for ice and south for north. His chance to do so came with his appointment in late 1939 as an official war artist. In the last three years of his life, as Davidson finely puts it, “the snow and the snow-light on bare hills drew him steadily northwards”. He travelled to Scotland, and under dangerous conditions to Norway. Finally, in 1942, he landed a posting to Iceland. His friend Helen Binyon observed that Towne’s influence was at this time powerfully at work on Ravilious, enchanting him with dreams of ice and light. Towne’s work, she wrote, was “why his imagination was so taken with the idea of painting Iceland”.

And so Ravilious flew into Reykjavik in the late summer of 1942. From there he travelled by road to Kaldadarnes, the Anglo-American airbase on the east of the island. On 2 September, only two days after arriving in Iceland, he joined a search-and-rescue mission, flying as an observer to a crash site 300 miles out into the Atlantic. A storm blew in, and the Hudson carrying Ravilious pitched into the sea. He died out there in the northern ocean, drawn fatally to that point by the vision he had first discovered in Towne’s paintings.