Exterior of the Karl-Max Seifert lamp factory c.1906–7

We read descriptions, we imagine appearances, but so often our sense of how things look remains verbal. Yet sometimes there are photographs, and in the case of historical exhibitions these installation images – like the photos of other events that we first learn about through written accounts – fill out our inchoate imaginings and prompt new thinking. And they bring surprises. I once met two collectors who had become fascinated with the Ninth Street Show, a 1951 New York exhibition of first and second generation Abstract Expressionist artists. They had set out to obtain a work by every artist in the exhibition, but they had never seen Aaron Siskind’s photographs of it. And when they did, they were shocked by these images of works displayed in a rough, low-ceilinged space lit by bare light bulbs. For their vision of a contemporary art exhibition had been formed in museums and galleries of the 1980s places of spacious presentation in grand rooms with immaculate white walls.

Having read that the first Dresden exhibition of the members of the Künstlergruppe Brücke (Artists Group Bridge) was held in a lamp company showroom in the city suburb of Löbtau, I was not surprised by the inverted forest of ceiling fixtures dominating the only known installation photograph. But I had not imagined what kind of lamps would be there, if lamps were there at all, nor what the other furnishings of the room would be like. And it is in such details that our idea of an historical event becomes more solid, more substantial, more able to connect with other things that we know. Here were high-end Jugendstil lamps, well-crafted and elegantly designed, expressions of a movement that sought to overcome the alienation of industrial manufacture with artistic design and forge a more direct connection between producers and consumers. Hence this showroom next to the factory of Karl-Max Seifert, where customers could buy lighting fixtures where they were made and whose owner often employed artists to design his products.

The showroom in this photograph is a processional space intended for leisurely viewing of the company’s wares. And as a retail space designed for display, it reminds us of the relationship between the modern presentation of artworks and the development of the department store and other sites that employed a staging of visual experience in support of commerce. Yet contrasting with this link to public places is the domestic feel of the showroom’s appointments: comfortable chairs, tasteful wall coverings above white lacquered woodwork, intimate alcoves This use of domestic associations to aid the sale of luxury goods also evokes early displays of modern art, such as the third Impressionist exhibition in 1877 set in a bourgeois apartment rented for the occasion by Gustave Caillebotte, or dealer Paul Durand-Ruel’s 1883 conversion of an apartment into a gallery for the sale of Impressionist paintings.

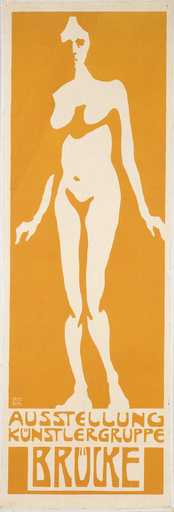

Poster for the first Brücke exhibition, designed by Fritz Bleyl 1906

© Courtesy The Brücke Museum

Fritz Bleyl

Walking Nude Girl 1906

Woodcut

© Courtesy The Brücke Museum

The Seifert showroom’s designer was Wilhelm Kreis, a professor at the Dresden School of Decorative Arts, for whom Brücke artist Erich Heckel worked as a draughtsman on architectural projects. It was Heckel’s connection to the construction of the showroom that seems to have led to the artists’ mounting the exhibition there from 24 September to late October 1906. One of the four Dresden architecture students who had come together the previous year as the Brücke – the others were Fritz Bleyl, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff – Heckel was the primary organiser of their business and exhibitionary activities. And the latter were considerable, for the Brücke showed as a group at least 70 times from 1905 to 1913. In fact, it was a requirement of membership to show one’s work only together with that of the other Brücke artists, and in 1912 Max Pechstein resigned from the group to exhibit on his own with the Berlin Secession. (Pechstein, Emil Nolde and Swiss artist Cuno Amiet joined the four original Brücke members in the Seifert exhibition.)

The design of the lighting showroom was modern and elegant, and in the photograph of the Brücke exhibition we see a tasteful, well-modulated display of paintings and watercolours in white frames that complement the white painted woodwork and furniture. Of course in this blackand- white photograph we cannot see the aggressive colour that characterised the work of these artists, nor the strong woodcut prints that became a hallmark of the Brücke. But to the right there is one intrusive element, a panel written in stark lettering that speaks of information and sales. Whether the sale of art or of lamps is unclear due to its illegibility in the photograph, but the ambiguity again reminds us of the relationship between modern commercial display and the presentation of modern art.

To accompany the exhibition, Kirchner created a woodblock print of the Brücke Programme, a manifesto that was also published as a leaflet. It states that “as young people, who bear within themselves the future of humanity, we wish to secure the freedom to live and work as we choose, in opposition to well-established older forces”. Extolling directness and authenticity of expression while living a bohemian existence in a working-class district of Dresden, these artists presented themselves in the Romantic terms of youthful rebellion. Their defiant stance was highlighted by the police prohibiting the use of Fritz Bleyl’s poster for the exhibition, an image of a naked young woman that was judged as too sexually suggestive to be displayed on city streets.

In apparent contrast to the idealism of its public persona, the Brücke actively promoted its commercial interests. Although its members failed to create their own exhibition space, the group’s ambitious exhibition programme – which included both one-off and circulating shows – regularly put Brücke work before the public and attracted other artists. And the membership structure itself produced revenue, consisting of artist “active members” and a larger number of non-artist “passive members”. The latter were patrons who paid a minimum annual fee of twelve marks, and who in return received a print portfolio. The first passive member was Karl-Max Seifert, and the first portfolio contained works by Bleyl, Heckel and Kirchner.

In December 1906 another Brücke exhibition opened at the Seifert showroom, with woodblock prints by group members and a few guests, including Wassily Kandinsky.

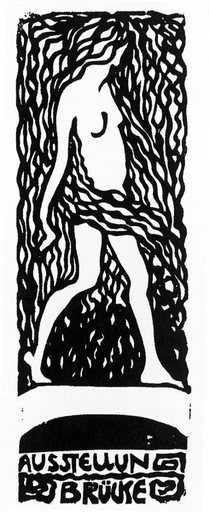

Erich Heckel's draft of poster for the first Brücke exhibition 1906

Courtesy The Brücke Museum © Erich Heckel Estate

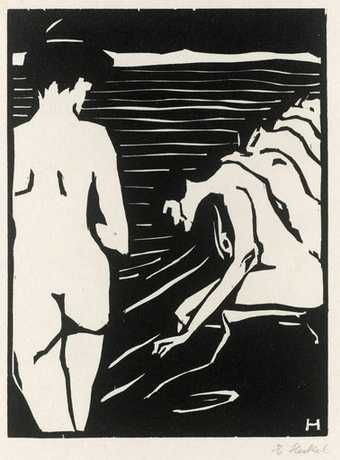

Erich Heckel

Female Nudes 1906

Included in the first Brücke portfolio

Woodcut

18.9 x 14 cm

Courtesy Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden © Erich Heckel Estate

The bond that these artists established with patrons, and their reducing the role of middlemen by arranging their own exhibitions, fit well with fundamental ideas of Jugendstil design and the Arts and Crafts Movement of which it was an expression. Here the Brücke’s passive membership and exhibition organising are analogous to Seifert’s building his showroom next to his factory. All were structures serving to connect more closely artistic producers and consumers, business strategies that were linked to utopian projects responding to the estrangement of modern life. But of course none of these efforts could overcome the pressures of urban and commercial disconnection, nor resolve the contradictions attending artistic work in a period of massive change.

We sense these hidden tensions in the scenography of this peculiar image, with its odd juxtaposition of a gaggle of lamps above an elegant display of pictures. Like a Magritte that shows a daylight sky above and a nighttime scene below, the bifurcated photograph of this exhibition of the Brücke both illuminates edifying details and suggests a deep disquiet. And by inverting the photograph we can see a strangely disturbing view of a world turned upside down.