Most of history is constructed with altered stories. Anecdotes mutate into myths, time and spaces are expanded or shrunk according to the needs of the historian. Gabriel Orozco is a paramount figure in the recent history of contemporary art. He has been a master both at creating memorable art and fictionalising its context – by transforming the mundane into the classical using objects such as yogurt pot lids and bicycle frames.

Gabriel Orozco

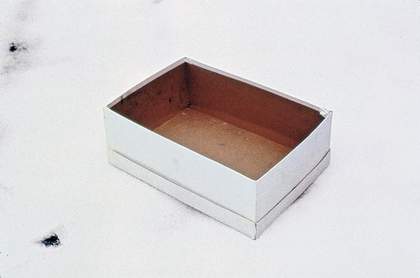

Empty Shoe Box 1993

Shoe box

40.6 x 50.8cm

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © Gabriel Orozco

I was part of his story in the early 1990s, of what I would call the “Orozchiad” – the coming of age of a young artist from Mexico to become a contemporary Picasso. His best known artwork, Empty Shoe Box 1993, now belongs to the trinity of conceptual art. At the centre is Duchamp’s urinal. To the right is Manzoni’s Merda d’artista 1961. And to the left is the “Holy Spirit” in the form of Empty Shoe Box. I want to tell my side of the story after reading two short paragraphs about Orozco and the shoe box on the occasion of his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The first sentence that caught my attention was in the catalogue of the exhibition in the section titled “chronology”, written by Paulina Pobocha and Anne Byrd. This sentence was also transcribed in the extended label that welcomed the visitor to the first room of the MoMA show. Referring to Empty Shoe Box, it said: “The miniature quality of the sculpture was an impish comment on the tiny display space.”

I was the curator who invited Orozco to the ‘Aperto 93’ at the Venice Biennale. He was included in a section of my exhibition entitled ‘The Mere Interchange’. I remember him rolling this ball of plasticine through the Corderie building and placing it in the space allotted to him between two gigantic brick pillars. Then, with a very humble gesture, he opened a knapsack and pulled out in front of a small group of friends his shoe box, and placed it in the middle of the proportionally immense space. The idea that such an uneventful object was taking up so much real estate caused quite a commotion among many artists. Space in a Venice Biennale exhibition is rare. Artists fight to defend every square inch for their work. Curators are threatened, people cry, voices are raised. When he saw the territory occupied by that shoe box (which looked like a caravan in Monument Valley), the American artist Charles Ray was up in arms. He and his assistants had been trying to place his 7½-ton painted white steel cube. It was a tense moment. I held my ground, protecting the box and its legitimate place, and the work remained where it was.

And now I read that the small cardboard box was “an impish comment on the tiny display space”. This was just wrong. It was turning a mythical gesture into a banal polemic, into an insignificant anecdote. I wondered if the artist had read the text. Was being impish more historically valuable than being brave and defiant? I will never know. It was only a few days later when I read the article in the New York Times by Deborah Sontag (11 December 2009) that I realised that facts had been shafted and history subverted in order to create some kind of more respectable chronology. Sontag wrote: “In 1993, the year that he created La DS, when he was also experimenting with sculptural globes of plasticine and inked circles atop toothpaste spit on graph paper, Mr Orozco’s career took off with multiple exhibitions. Among them was one that Ms Goodman arranged at the Venice Biennale, where he showed Empty Shoe Box, an open cardboard box left on the floor to be kicked about. ‘It shocked everybody,’ Ms Goodman said. ‘He has a lot of courage in what he does and can be quite radical.’”

I was confused by this story. The dealer Marian Goodman was definitely the motor behind my encounter with the young artist, who had just arrived in town, but again the real story was very different, and I believe it is worth telling. One evening I was invited to Goodman’s home after the opening of a show. At dinner I was seated next to a very shy artist with a corduroy jacket and a pony tail, who was introduced to me as Gabriel Orozco. Near us was the Don Vito Corleone of institutional critique, Benjamin Buchloh, whom I didn’t know, but who had already dispensed his blessing over Orozco’s work. Orozco and I got on well, and since we were living on the same street in New York, we started hanging around quite a bit, both penniless but enthusiastic about an art world which didn’t manifest itself as a power machine that can ruin many friendships and good relationships. (Gabriel and I are still friends, and hopefully will remain so after this article is published.)

Gabriel Orozco

My Hands Are My Heart 1991

Two cibachrome prints

Each 22.8 x 33 cm

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © All images Gabriel Orozco

Gabriel Orozco

My Hands Are My Heart 1991

Two cibachrome prints

Each 22.8 x 33 cm

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © All images Gabriel Orozco

It was a time when so-called “global” or “post-colonial” art was barely making an appearance. But the Venice Biennale has always been an international event and, even then, the safari for artists from less popular countries was underway. The ‘Aperto’ curator was Helena Kontova, then editor in chief of Flash Art magazine. I liked Orozco’s early pictures and the “invisible” interventions that he did, but to bring him to the attention of the biennale’s main curators was a long shot. Eventually, in a meeting close to the final selection of artists, I found an opportunity to present Gabriel’s work. Nobody really paid much attention, but there were two questions: “Where is he from?” someone asked. Mexico was my answer. “How many Mexicans do we have in the show?” someone else asked. None, I said. “Invite him!” was the response. So you could say that his participation was more down to his country of origin, his roots, his Mexicanidad. He knew that, and played along with it on his arrival in New York very skilfully.

Later, I found out that the Orozco in Mexico City was not the same Orozco I knew in New York. He was already a strategic player. Someone with the self-esteem of a Picasso, when asked “what do you want to be when you grow up?”, he would have answered “Gabriel Orozco”. I can compare him with Zorro, the fox, even if his nickname on the football field was “el pájaro” (the bird), on account of his ability to move fast and avoid the adversary. The man I met at Goodman’s dinner was like Don Diego de la Vega, the shy nobleman under whose identity Zorro was hiding. Gabriel played this double role in order to enter the sealed-off New York art world. The shy Mexican was able to infiltrate the “first world” system and manipulate it – building his own history, adjusting stories, or altering reality. He was a master. His “godfather” Buchloh was mesmerised. But “Orzorro” was his own Michael Corleone in Mexico, ruling the art world according to his theories and ideology. The oral history of his rule tells that he even had his “Fredo” in the figure of the artist Gabriel Kuri, the brother of Orozco’s dealer in Mexico City, José Kuri. The poor artist committed the offence of accepting an invitation to participate in a group show organised by Cuauhtémoc Medina, a “sworn enemy” of the Orozchian faction. Gabriel Kuri was not disposed of on a small boat in a lake like Fredo in The Godfather II: he moved to Belgium, where he enjoys a flourishing career.

Gabriel Orozco

Yielding Stone 1992

C-type print

40.6 x 50.8 cm

Orozco truly played this role of a kind of Zorro for contemporary Mexican art, freeing an entire generation from the shackles of folkloric moods and their “siqueritudine” [the followers of the social realist muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros]. But he also functioned as the Godfather of the same generation, both generous and ruthless. As with all heroes, the risk and the temptation to transform excitement into veneration and finally into a sort of aesthetic dictatorship has always been present, and Orozco has not been immune from it. Which brings us back to the falsehood of small but essential details relating to the description of Empty Shoe Box. Maybe for any artist who overcomes the firewall of success, remembering genuine small gestures of true courage but of a lesser God, such as pulling out a shoe box from a knapsack and placing it on the bare ground in front of an astonished and angry mob, means recalling a time when all was uncertain and everything impossible. A true hero likes to indulge in being impish, because impishness brings back that humanity he was forced to shed along the road – with the corduroy jacket and Mexicanness once so easily patronised.

This is my “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Mexican”, which is modest and autobiographical. Today, the Gabriel Orozco story is different, and has become more epic.