Leonardo da Vinci advised the budding artist with creative block to leave behind his blank canvas and stare at the stains on walls: ‘If you look upon an old wall covered with dirt, or the odd appearance of some streaked stones, you may discover several things like landscapes, battles, clouds, uncommon attitudes, humorous faces, draperies, etc. Out of this confused mass of objects, the mind will be furnished with an abundance of designs and subjects perfectly new.’ Leonardo’s technique, which encouraged the viewer to search for meaning in chaos, referred back to myths about the origin of art in accidental shapes. In De Statua, Leon Battista Alberti supposed that artistic imitation emerged when our ancestors came across a gnarled tree trunk or a piece of clay, whose contours ‘needed only a slight change’ to look strikingly like something else. Renaissance artists employed all kinds of tricks that played with these ancient, shape-changing ideas. Mantegna secreted zephyrs in the billowing clouds of his paintings, Bellini’s rocks hid human faces and the folds in Dürer’s drapery contained a camouflaged catalogue of physiognomic types. Nature is shown to be a repository of readymades, if only you are patient enough to look for them.

Albrecht Dürer

Study of Drapery 1508

40x23.5 cm

Private collection

Alexander Cozens and a pupil

A Blot, Based on New Method, Plate 10. Verso: A Clumsier Blot ()

Tate

However, it was only in the eighteenth century that a systematic unpacking of Leonardo’s idea of cultivated chance began. It happened, appropriately, by accident. Alexander Cozens, an English landscape painter famous for his study of neoclassical beauty, was illustrating something to a pupil with a quick sketch when he noticed that what he’d drawn had been unconsciously affected by the pre-existing marks on the soiled page. ‘The stains,’ he wrote, ‘though extremely faint, appeared upon revisal to have influenced me, insensibly, in expressing the general appearance of landscape.’ Using a wet brush dipped in stronger ink, he deliberately made some marks on another piece of paper, and instructed his student to turn the blots into a landscape. The previously hesitant boy’s power of composition was freed, and an easy method for generating new landscapes was born.

According to another student, Cozens sometimes splashed plates with blots of ‘all the colours of the rainbow’ and pressed into them crumpled sheets of paper, which he worked up with swift strokes (Botticelli, Leonardo noted, used to throw sponges drenched in colour at the wall to create his landscapes, but was a ‘sorry’ painter of them). Whereas amateurs sometimes struggled to make acceptable scenes out of ‘great splashes of brown’, Cozens’s own rigorous training allowed him to achieve the desired broad effects:

‘It could be observed that where his pupils failed,’ wrote one of his students, ‘his masterly hand touched their works into something like an appearance, as he used to say, and superadded on the seas, lakes, rocks and promontories, ships, boats, trees and figures, as circumstances permitted.’

Alexander Cozens

Plate 6 (c.1785)

Tate

Cozens had been a pupil of Claude-Joseph Vernet in Rome and valued the poetic, imaginary landscape over the slavish imitation of exact topographical representation. According to his biographer AP Oppé, his visual vocabulary was fed by descriptions of far-flung lands from books such as Captain Cook’s Voyages, and his blot technique, articulated in A New Method of Assisting the Invention of Drawing Original Compositions of Landscape (1785), lent itself to these ideal, fantastic conceptions. The book contains sixteen aquatint reproductions of Cozens’s instantaneous‘blot paintings’, with mezzotints of the finished drawings he made from them. They show a kind of spilled sublime. Cozens skilfully transforms sploshes of ink into teetering architecture, exaggerated mountains, gloomy dells, stormy skies and melancholy ruins. While the subjects are of their time, the raw energy of his gestures look very modern.

Cozens was mocked by some of his contemporaries for his child-like technique (the painter Edward Dayes dismissed him as ‘Blotmaster-General to the town’), and was characterised as a charlatan. He appealed to Leonardo’s precedent in his defence and even claimed to have improved on the creative ideas of the Renaissance genius with his man-made accidents. Joseph Wright of Derby experimented with blot painting and owned work by Cozens, as did George Romney. The humble blot, which seemed to contain an infinity of possible worlds, might be seen as the seed of Romantic notions of genius: ‘The use of blotting may be a help even to the genius’ Cozens argued, ‘and where there is latent genius, it helps to bring it forth.’ Constable, who copied Cozens’s clouds to prepare for his own free studies of the sky, wrote that ‘Cozens was all poetry’, and his technique for inserting randomness into the creative act inspired a new generation of painters such as J.M.W. Turner. This process was not without controversy: in 1877 John Ruskin accused J.M. Whistler of ‘flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face’.

Justinus Kerner

Klecksographie 1890

Ink on paper

Courtesy Universitat Bibliothek Heidelberg

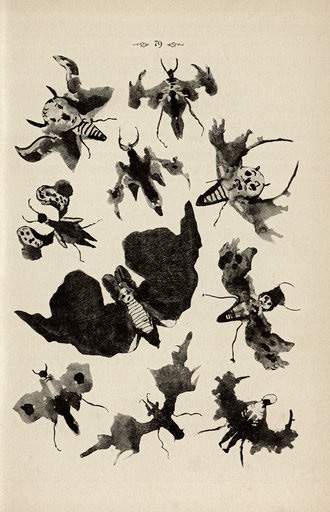

Cozens saw only landscapes in his blots, and encouraged his students to see the same, but others discerned more sinister things. The doctor and poet Justinus Kerner, who was born the year after Cozens’s book was published and moved in German Romantic circles, transformed the accidental smudges he made in letters to friends by doodling them into diabolical shapes. He later made these deliberately, folding the paper to create symmetrical forms, which he elaborated into a bestiary of grotesque ‘creatures of chance’. In 1857 he published a book of these Klecksographien (from Klecks, meaning smudges or blots), which he juxtaposed with whimsical verses on the theme of memento mori. A spiritualist, who investigated possession and animal magnetism in his medical work, Kerner thought these images came to him from ‘Hades’ and ‘the other world’. As a result, he predominantly saw ghosts in the random shapes: skeletons, skulls, demons, bats, winged monsters and other Halloweenish forms.

Blotto, which involved making random marks and decoding them, became a popular parlour game in the late 1850s. With its suggestion of the occult, it was as though, through random stains (as might be read in tea or coffee granules), the dead were in some way communicating with the assembled players. Victor Hugo was another enthusiastic amateur blotter, and in his ‘Tache’ or ‘stain’ paintings he shares Kerner’s predilection for gothic phantasmagoria. After his daughter Léopoldine tragically drowned in the Seine, Hugo used Ouija boards to try to communicate with her. He claimed to have been able to summon her ghost in seances, along with those of Dante, Galileo, Voltaire, Moses, Jesus Christ, Death and the ‘Ocean’, which flooded him with waves of expletives. Sometimes he would replace one of the legs of the planchette with a pencil, so that a spirit might communicate in a continuous line drawing as it moved the planchette around the board.

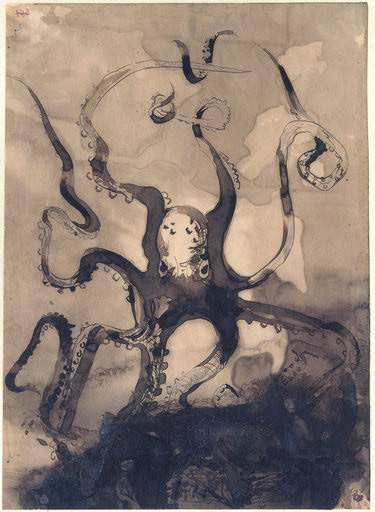

Hugo’s sophisticated blot-inspired pen-and-ink drawings were, he wrote, ‘for private use and to indulge very close friends’. The majority were created when he was in political exile in the Channel Islands, where he lived from 1851 to 1870 in protest at Napoleon III’s unlawful seizure of power: they depict shipwrecks, gallows, Piranesi-like staircases, haunted landscapes, spiky castles and crumbling cities in muddy, sepia tones, which seem to emerge from the page as though approached through thick fog.

Hugo’s friend Philippe Burty said of his technique: ‘Any means would do for him – the dregs of a cup of coffee tossed on old laid paper, the dregs of an inkwell tossed on notepaper, spread with his fingers, sponged up, dried, then taken up with a thick brush or a fine one… Sometimes the ink would bleed though the notepaper, and so on the reverse another vague drawing was born.’ Hugo also folded the smudged paper to create abstract rosettes, and applied ink-soaked lace to create skeletal venations. A sense of threat lurks beneath the surface of much of his imagery. (It was rumoured that he used blood pricked from his own veins in his many drawings.) In one sketch a giant, menacing octopus, fashioned from a single stain, contorts its suckered limbs into the initials VH.

Victor Hugo

Octopus with the initials V.H 1866

Pen and ink wash on paper

35.7 x 25.9 cm

Courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris, France

The Surrealists venerated Hugo’s art, though they abhorred his literary sentimentality. ‘Victor Hugo is a Surrealist when he is not stupid,’ declared André Breton, who was for a while the lover of the ex-wife of Hugo’s grandson. She introduced him to Hugo’s drawings, which he praised for their ‘unequalled power of suggestion’. Cocteau and Picasso also owned several of Hugo’s feverish creations, and they influenced the development of Surrealist automatism. However, Breton distinguished the Surrealists’ method from spirit channelling, referring to Hugo’s Jersey séances as ‘productions… of astounding naivete’.

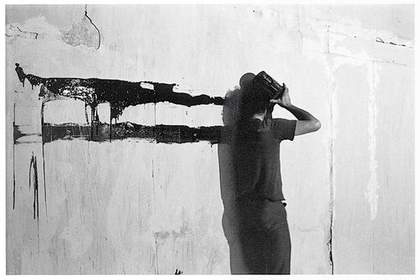

In one of Man Ray’s photographs of a trance session conducted by the Bureau of Surrealist Research in 1923, the poet Robert Desnos is shown at the typewriter. According to Breton, he was particularly good at entering ecstatic states and bypassing conscious control: ‘Put yourself in as passive, or receptive, a state as you can. Forget about your genius, your talents,’ advised Breton, thereby differentiating Surrealism’s automatic productions from Cozens’s nascent Romanticism. ‘After a quarter of an hour, Desnos…lets his head fall on to his arm and begins to scratch compulsively on the table,’ Breton wrote of one of these sessions. In drawings such as Sinister Human Encounters 1922, Desnos has scribbled a network of pencil lines with his eyes shut, and then created images from these abstract doodles. He described this technique with reference to Leonardo. The ‘tangled web of lines’, he wrote, was a product of chance, while the figures that ‘appear suddenly from this chaos [are] born somewhat like those one sees in clouds or in the cracks in walls’.

André Masson also created drawings in a state of trance. ‘The first graphic apparitions on the paper are pure gesture, rhythm… pure scribbles,’ he explained. ‘In the second phase, the image (which was latent) reclaims its rights… suddenly ones sees arise a hand, a vegetal or animal fragment… When the image appears one must stop.’ The resulting drawings are dense tangled webs that seem to contain their own little worlds: anarchic, swirling constellations, labyrinths, or coral reefs. Masson confessed to a ‘visceral obsession” – an interest in ‘wounds, injuries, mutilation’ (traumatic results of his wartime experiences) – and some of his drawings resemble dismembered bodies with their organs exposed.

Whereas spirit channelling dissociated the creator from his productions, the Freudian theory on which Surrealism was based reunited them. In a letter to his future wife Martha Bernays (dated 9 August 1882), written almost two decades before The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Freud excused a slip of the pen: ‘Here the pen fell out of my hand and inscribed these secret signs. I beg your forgiveness and ask that you not trouble yourself with an interpretation.’ One’s blots, even before one elaborated them, might reveal a stain on one’s character. How much more might be revealed in one’s doodles? Many of Masson’s drawings had an erotic charge; the imagery that presented itself from the unconscious, he explained, was often ‘embarrassing, disquieting, unspeakable’.

Alex Hubbard

Lazy Man’s Load 2 2010

Resin, fibreglass, oil and acrylic on canvas

213.2 x 152.4 cm

Courtesy Simon Lee Gallery © Alex Hubbard

In 1921 the Swiss psychologist Hermann Rorschach, whose father was an art teacher and whose childhood nickname had been Klex (ink blot), began subjecting schizophrenic patients to his famous ink-blot test. Influenced by Kerner and Freud, he created ten symmetrical plates that were presented to the subject in a predetermined order, the doctor simply asking: ‘What might this be?’ The blots were designed to trigger free associations, and to offer data that would enable the psychologist to make judgments of character: the bats, skeletons and moths you saw revealed something about you. Those whose answers emphasised movement, for example, were likely to be introverted; those who exhibited ‘colour shock’ when shown the first colour plates were repressed; and those who obsessed about details were pedants and grumblers.

Rorschach died at the premature age of 37, the year after his book Psychodiagnostik (1921) was published, but in the 1930s psychologists at Columbia University, looking for a test that would provide broad insight into human motivation, became enthusiasts and popularisers of his scheme. Psychologists administered his test at the Nuremberg trials, unsuccessfully attempting to define the Nazi personality, and it is still used today. The bi-symmetrical blot became a recognisable part of popular culture – a symbol in itself of the mind sliced open and examined. In 1935 Marcel Duchamp created his own versions for the cover of the Surrealist journal Minotaure, turning the ink blots into a bearded, staring, horned form. It was as though the movement was trying to claim back the artistic method that had now become thoroughly medicalised.

George Grosz, the German painter associated with Berlin Dada, nicknamed Pollock a ‘Rorschach-Test-Rembrandt’. In the enthusiastic critical response to Pollock’s machismo gestures, and in the ‘stain paintings’ of his fellow Abstract Expressionists such as Helen Frankenthaler and Kenneth Noland, the smudge became an index of personality, a cardiogram of the unconscious. Grosz implied that the Abstract Expressionist’s use of blotting was, in reality, merely decorative, like lace. In 1984 Andy Warhol created his enormous, 13½ ft high, gold and multicoloured Rorschach Paintings. If his oxidisation series of the late 1970s, in which Warhol urinated on canvases covered with metallic paint, had mocked Pollock’s drip painting, the Rorschach series might also be interpreted to ridicule any pretension to be able to read anything about the artist’s intention below the surface. Blown up to menacing proportions, his ink blots remain obstinately meaningless.

Warhol joked that he was going ‘to hire somebody to read into them, to pretend that it was me, so that they’d be a little more… interesting. Because all I would see would be a dog’s face or something like a tree or a bird or a flower. Somebody else could see a lot more”. Nevertheless, the images seem to invite the projection of sexual meaning, but that was, as Ernst Gombrich termed it in Art and Illusion, wholly the ‘beholder’s share’. In Pornographic Drawings 1996, Cornelia Parker plays on the Rorschach blot’s erotic charge, creating phallic smears with ink made by dissolving pornographic videotapes that were confiscated and shredded by Customs and Excise.

‘Chance art, as expressive of modernity, is therefore uniquely and necessarily modern,’ wrote Hans Arp. The fabrication of accidents (what Duchamp called “canned chance”) has been a key component of modern art, and artists often refer to the idea’s long history. Francis Bacon threw paint at the canvas, perhaps in homage to Whistler: ‘My ideal would really be just to pick up a handful of paint and throw it at the canvas and hope that the portrait was there,’ he told David Sylvester. Sigmar Polke’s ‘poured pictures’, such as Séance 1981, were made by moving a table as though at a spiritualist seance; the image emerged like a spirit painting, untouched by human hand. In Vik Muniz’s Equivalents series 1993, clouds assume the shape of Dürer’s praying hands, or a postprandial plate of spaghetti reveals a Medusa head.

All these works play on the tension between accident and intention, in how the eye and brain work together to, as Muniz calls it, create ‘accidental’ or ‘multi-stable images’. Throughout history the blot has been the rawest and most blatant expression of artistic debates about interpretation. If all art is, in one way or another, ‘seeing things’, and if all art criticism is interpretation – or, as Susan Sontag says, against it – then blots and stains and graphic accidents are, as Alberti suggested, the basis of all art. The meaningless stain, which invites the universal urge to project meaning, is the humble stage on which all arguments about art are rehearsed.