What do we mean when we say that a language is dead or dying? This curious bit of reflex anthropomorphism with regard to the passing of a spoken tongue is, it turns out, a relatively modern habit. It would have made no sense, for example, to the classical Greeks, for whom the works of Homer already contained archaic (but not deceased) idioms, nor to medieval Jewish scholars who read ancient Hebrew as sacred and incorruptible, untouched by linguistic mortality. It seems it was only in the Renaissance that languages no longer current began to be described in terms best suited to defunct organic beings.

Susan Hiller

Magic Lantern 1987

Tape/slide programme, three slide projections and a soundtrack

© Susan Hiller

Today, linguists distinguish several states of ailing or peril among languages that are on their way out, among them “endangered”, “potentially endangered”, “seriously endangered”, “nearly extinct” and “moribund”. This last denotes languages whose elderly speakers have not passed their competence on to their children – when they fall silent for good, a whole world view will vanish.

;Susan Hiller

Still from The Last Silent Movie 2007–8

Single-channel projection on Blu-Ray Disc

© Susan Hiller

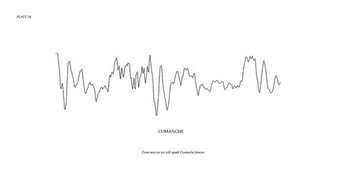

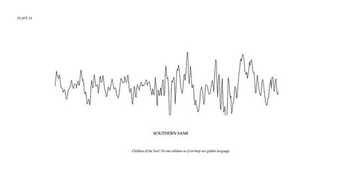

Some of these terms appear in Susan Hiller’s The Last Silent Movie 2007, a video installation that presents sound recordings of the last (or almost the last) speakers of certain languages. There are no images, just a black screen on which subtitles appear, interspersed with the details of each language and its proximity to extinction. Voices crackle into life: singing, reciting, reflecting on the imminent silencing of their words and seeming to admonish us across the decades. (Such voices vanished at a vastly accelerated rate in the last century – in 1995 it was estimated that more than half the world’s languages were moribund.) The recordings have come from various academic archives, so that one might say the voices were silenced twice over: consigned to the status of mere relic or exemplar, their dates and locations tabulated but the living person irretrievably reduced. Except of course that they have a new spectral and affective life in Hiller’s work; viewers (if that’s the word) of this piece are typically rapt at its sheer emotional force.

Susan Hiller

Still from The Last Silent Movie 2007–8

Single-channel projection on Blu-Ray Disc

Photo: Todd White Art Photography

Susan Hiller

Still from The Last Silent Movie 2007–8

Single-channel projection on Blu-Ray Disc

Photo: Todd White Art Photography

The Last Silent Movie is among the most apt examples of the rigorous ambiguity of Hiller’s art, which since the early 1970s has described a compelling course between austere Conceptualism and various types of knowing irrationalism. In fact, that is putting it too crudely, and it has become something of a critical commonplace where Hiller is concerned to say that the organising schemas in her work – museum-like vitrines, abstracting grids, para-academic “research” – are at odds with the sometimes brazenly personal or fantastic content. It’s certainly true that her early work scandalised Conceptualists proper with its subjective turn. But it would be more accurate to say that her peculiar (though now much imitated) domain was rather the interstices of the Conceptual grid: the tendency of intellectual and linguistic systems to breed Romantic monsters, not to speak of embarrassingly urgent or dreamy instances of the personal-political that Conceptualism, with its cool emphasis on demystification, worked strenuously to deny.

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum (1991–6)

Tate

As with the ghost voices of The Last Silent Movie, it’s often a matter of the revenant anecdotes or particularities which seep through the seemingly rational scrim that the artist puts in place. Consider what remains, perhaps, her best-known work: From the Freud Museum 1991–7. Here, safely vitrined, is a series of archival boxes – there were originally 22, now 50 – in which artefacts that point to the real history of psychoanalysis vie with relics and inventions of uncertain, suggestive and at times unreadable provenance. Fetish objects, Ouija boards, Punch and Judy props, vials of holy water labelled with the names of sacred springs: these appear to be subject to anthropological investigation, sedulously annotated and organised. But the presiding logic is missing, and the installation gives rise instead to varieties of fascination and conjecture. Science blurs with pseudo-science, and lived histories (of religious devotion, of occult practices, of the medicalised female body) start to float free from the ostensibly rationalist structure. From the Freud Museum is as much a wry perversion of scholarship itself as it is of the supposedly demystifying methods of the Conceptualism it deploys. Despite their best efforts, both (so Hiller insinuates) will unleash unruly phantoms.

Both From the Freud Museum and The Last Silent Movie play too upon the intimacy and distance that language allows with respect to its object – written words here delineate the image or sound perceived (illustrate it in a sense) and at the same time fail to match it, leaving space for imagination and fantasy. But what’s at issue is not simply the failure of language – instead, Hiller is interested in the seductive or troubling gaps between word and image, or between sound and text. In certain cases, what emerges is a whole aesthetic inheritance, somewhat ironised by the system or structure that is both organising principle and means of display.

Susan Hiller

Dedicated to the Unknown Artists (detail) 1972–6

305 postcards, charts, maps, one book, one dossier, mounted on fourteen panels

Each 66 x 104 cm

Photo: Todd White Art Photography

Dedicated to the Unknown Artists 1972–6 is composed of more than 300 black-and-white and colour postcards bearing the legend “Rough Seas”, and a quasi-curatorial description of the images that notes the places depicted, their format (vertical or horizontal) and their precise printed addenda. The form is sober and the impetus apparently of a piece with Conceptual concerns: in part, it’s a work about the conventions and clichés of a certain kind of popular image. But there are at least two types of excess here also – in the simple profusion of images (producing an eccentric collection where none existed before), and more intriguingly in the quotidian return of an aesthetic of the sublime, a venerable (and very English, for this displaced American artist) fascination with the places where an island nation meets the threatening ocean. And once more it’s a question too of what one doesn’t see: an anonymous “artistic” tradition unearthed by Hiller’s cultural archaeology.

Susan Hiller

The J. Street Project (Snow Scenes) – detail 2003

Three piezo prints with pigmented inks on Hannemühle William Turner paper

Each: 100 x 70 cm

© Susan Hiller

Susan Hiller

The J. Street Project 2003

Artists’s book, collection of 2000

Photo: Tate Archive

Something of the same semantic exchange between image, text and unseen history circulates in The J. Street Project 2002–5: a film, photographic series and wall display which record the 303 thoroughfares (streets, alleyways, modest paths) in Germany that are still named for the Jewish communities that once resided, worked or traded there. “Still named” is not exactly the phrase here, of course, because what Hiller has archived is a series of places that lost their names in the Nazi era and have since had them reinstated. There remain many others where the name – “Judengasse” or “Jüdenstraße” – was not restored. The layers of denotation and disappearance are vexing and ambiguous: street names that once signalled difference and stigma are now intended to bear witness to the ultimate and horrific outcome of centuries of anti-Semitism, to point to and remember (if not actually name) the disappeared. But as Hiller’s film demonstrates, contemporary life carries on around these traumatic inscriptions as though they were not there: the memorial name becomes just another textual element (ignored by passers-by) in the street furniture of the modern city, so that it is entirely unclear if it functions as a means of recall or amnesia. That uncertainty attends also the images that Hiller makes of the street signs and their environs. They memorialise historical presence and more recent absence, but that function is both over-determined by the quest or pilgrimage structure of the work – the artist visiting all 303 sites in turn – and abstracted by the structure of the series itself, so that the work shuttles between the sense of an enlarging typology and the imagined specifics of deportation, killing and everyday cultural erasure.

Hiller’s art has long been exercised by the paradoxes inherent in acts of witness, which both appeal to a concrete reality (even if observed by only a single speaker or writer) and rely on the witness’s ability to conjure rhetoric and imagery out of the ether. This is nowhere more in evidence than in the many works she has made with an occult or supernatural theme or resonance. Witness 2000 is the most insistent example: an installation composed of small speakers suspended at different heights from the gallery ceiling, from which (in various languages) accounts of UFO sightings (and closer encounters) are related. In one sense, the anecdotes told are the stuff of sci-fi and horror cliché: “I was glowing. Everything was glowing… It was a marvel… It landed on the roof of the car…the heat was intense… It was awful, frightening, like our brains were being sucked out.” One could hear them as illustrations of a kind of cultural contagion, quickened with reference to certain cinematic examples. But the voices seem to emanate from a more elemental realm. One doesn’t need to credit the artist with belief in a communal unconscious from which visions of alien craft and creatures emerge – rather, a more indeterminate field of narrative possibilities seems to be explored, and it belongs as much to the dreaming listener as to the narrating “witness”.

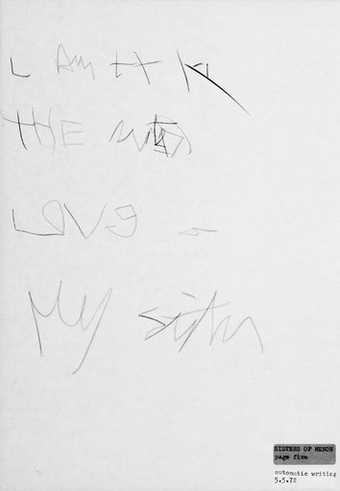

Susan Hiller

Sisters of Menon (detail) 1972–9

Automatic writing on A4 paper arranged on four L-shaped panels with typed labels; commentaries on four panels, typescript and gouache on paper

Each: 31.8 x 23 cm. Overall 91.2 x 64.2 cm

Courtesy the artist and Timothy Taylor Gallery, London © Susan Hiller

Much of Hiller’s early work seems an effort to access this uncanny space or time of supra-rational experience, all the while courting – and this is the source of some of the humour in her art – accusations of exoticism or credulousness on the part of the artist herself. Sisters of Menon 1972–9 involved experiments in automatic writing, subsequently exhibited on L-shaped panels in a cruciform arrangement. For Dream Mapping 1974 she invited a number of people to sleep inside “fairy rings” of mushrooms in a Hampshire field, then to draw maps of their dreams so as to investigate the notionally shared structures that subtended their nocturnal thoughts and apprehensions. In 1999 she completed Psi Girls, a five-screen installation in which examples of young women performing feats of telekinesis or telepathy were culled from cinema (mostly from horror films, but also from the likes of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker) and overlain by vividly coloured filters. They recall nothing so much as the semi-staged photographs of female hysterics produced by the psychiatrist Charcot at the end of the nineteenth century.

Susan Hiller

Psi Girls (1999)

Tate

Susan Hiller

Dream Mapping 1974

Black and white photograph

Photo: David Coxhead

Courtesy the artist and Timothy Taylor Gallery, London © Susan Hiller

Such works point also to the occluded relations between the modernist or avant-garde art of the last century and all manner of occult, spiritualist and supernatural beliefs. Two projects of Hiller’s have recently sought to restore and reactivate something of this inheritance. Homage to Marcel Duchamp 2008 collects photographs of ostensible auras surrounding individual faces or bodies. The art historical reference is a surprising one: Duchamp’s Portrait of Dr. Dumouchel from 1910, in which the subject’s body (and most notably his outstretched hand) appears haloed in light. The second series takes Yves Klein’s Leap Into the Void of 1960 as the impetus for a photographic archive (amassed from the internet) of individuals engaged in acts of levitation: magical, jocular, spiritually impelled, or in avowed homage to Klein himself. What both series seem to say is that we may try to expunge such fantastical acts and beliefs from the history of art, but they will likely return freed from irony and expressing a troublesome sincerity.

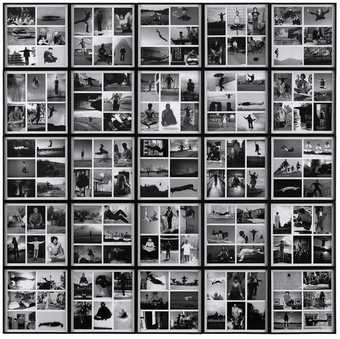

Susan Hiller

Homage to Yves Klein 2008

150 black-and-white digital photographs

Overall: 170 x 170 cm

© Susan Hiller

In his study of the ways in which language can vanish, Echolalias 2005, the critic and theorist Daniel Heller-Roazen points out that it’s not so easy to grasp the instant at which a spoken tongue “dies” – it may already be effectively defunct before its last speaker expires, or it may persist, ghostlike, in recordings and memory. “It is as if the critical moment continued to slip away from the scholar who would grasp hold of it, as if there were an element in the vanishing language that resisted every attempt to record and recall its definitive disappearance.” Susan Hiller, we might say, is a connoisseur of this kind of uncertainty, an artist for whom the heard and unheard, the seen and unseen, describe the limits of the territory that interests her. It’s in this intermediate place that such terms as “memory”, “witness” and “archive” – so easily applied to her work – become truly charged with knowledge and potential, and the most unprecedented actions and images are made manifest.