Klaus Kertess on the development of watercolour painting

While watercolour painting was not exclusive to the British Isles, it certainly seems to have been practised here more than anywhere else – especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when it was so frequently taken up by itinerant painters and well-educated ladies. Perhaps being surrounded on all sides by water intensified the British propensity for the medium.

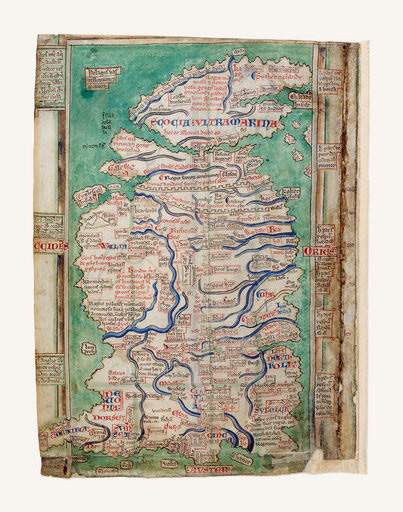

Matthew Paris

Map of the British Isles 1250

Pigments on vellum

Courtesy The British Library

Maps, such as Benedictine monk Matthew Paris’s Map of the British Isles c.1250, were among the earliest works in watercolour. Unique in its conflation of aesthetics and utility, map-making was practised by Greek and Roman cultures in the sixth century BC, and even earlier in China and India. In addition to guiding seafaring explorers, they were created to define the boundaries of property, or as aids to future military operations, as can be seen in Francis Hill’s Map and description of all ye Lands belonging to Richard Bridges Esq in 1707 – some 300 years before the far more mundane and invasive arrival of Google Earth. Meanwhile, some artists simply took pleasure in the representation of landscape – Wenceslaus Holler’s depictions of Tangier c.1669 and John Dunstall’s lively portrayal of A Pollard Oak Near West Hempnett Place, Chichester c.1660 – and laid the foundation for countless British watercolourists of the future.

Flemish illuminated manuscripts, both sacred and profane, had a strong influence on the development of British miniature portrait painting in the sixteenth century. Lucas Horenbout moved to England in 1525 and became court miniaturist to Henry VIII. He painted at least four miniatures of the king, as well as a number of portraits of Henry’s succession of wives. Horenbout is credited with being the founder of the tradition of British miniatures that stretches from the early sixteenth century to the present and encompasses the work of the unknown artist who produced An Eye Miniature Set with Pearls. There were two other seminal sixteenth-century miniaturists – Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619), who painted in the court of Elizabeth I and executed a particularly fine portrait of the monarch, and Isaac Oliver (c.1565–1617), who studied under Hilliard and whose art can be typified by the mysteriously beautiful portrait of an Unknown Melancholy Man c.1595. The miniaturists carried on into the nineteenth century – John Smart (1741–1811), among them – before their ranks thinned out.

Watercolour artists were greatly inspired by natural history, and there is an exquisite profusion of botanical and zoological illustration from the sixteenth century into the twentieth, from Georg Dionysius Ehret’s Study of Asphodeline Lutea with Two Butterflies 1747 to Sarah Stone’s almost Surreal still-life Study of Shells and Coral (eighteenth century), perhaps part of her vast record of the specimens from the New World in the collection of Sir Ashton Lever. While the invention of the camera would obviate the documentary function of botanical watercolours, they continue to provide aesthetic pleasure to the present day, as can be seen in Margaret Mee’s Neorgelia Margaretae 1979.

Educated ladies politely took to this lucid medium, such as Lady Gordon with her picturesque interpretation of the Cottage at Wigmore 1803, and male painters were no less drawn to the picturesque. Thomas Girtin produced his dizzying upward view of Bamburgh Castle in 1797. And then, of course, there was J.M.W. Turner, who increasingly infused his landscapes with a beauty resonating with the spiritual, seen in such works as two dazzlingly misted views of the Blue Rigi mountain, in the Swiss Alps, created in 1842 and 1844. The notion of watercolours produced for exhibition as works in their own right (previously they were considered only sketches) was championed by Turner with the likes of his sumptuous The Scarlet Sunset 1830–1840, a painting that prefigures French Impressionism. Watercolour can also probe darkness as eloquently as oil paint. For example, consider Eric Taylor’s Human Wreckage at Belsen 1945 with its vividly rendered harvest of dead bodies, Charles Bell’s Sabre Wound to the Abdomen 1815 and various depictions of facial aberrations. One of the sections in Tate Britain’s Watercolour exhibition is titled ‘Inner Vision’. This includes William Blake’s The River of Life c.1805, with its all but disembodied figures floating in the landscape, which leads the way into more imagined worlds by the self-taught and Blake-influenced Samuel Palmer, whose eerily beautiful A Hilly Scene c.1826–8 is also on show.

By contrast, the Pre-Raphaelites Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones raised their brushes in favour of a simpler, morally pure world. ‘Inner Vision’ also incorporates a section entitled ‘Dream’ demonstrating the heightened subjectivity of later watercolour practice – from David Austen’s cartoony, skinny pneumatic figures that might well look back to childhood fantasies to Tracey Emin’s pictures from her painted journal Berlin the Last Week in April 1998.

Where will watercolour go in the future? A question raised perhaps in the work of Karla Black, who pushes the medium to delirious limits in her Opportunity for Girls 2006. It is a piece composed of cellophane, watercolour, emulsion, acrylic paints, vaseline, glass, shampoo, hair gel, toothpaste and thread whose umbel twists and turns, whether consciously or not, seem to hark back to the suavely curving brushed ink paintings that began in China some 4,000 years ago.

Klaus Kertess is an independent curator and art writer.

Jerry Brotton on Matthew Paris’s Map of the British Isles c.1250

Map, painting, or manuscript? Around 1250 the Benedictine monk Matthew Paris drew the earliest map of Britain, the finest of four others, all of which grace the pages of his manuscripts on ecclesiastical and historical subjects. It is a map because it shows for the very first time a recognisable outline of England, Scotland and Wales, with north at the top. But the Wash and Cardigan Bay are missing; Scotland hangs on by the thinnest of peninsulas; and on closer inspection, everything is defined by a spine of towns and cities running from Durham in the north to Dover in the south. Near the bottom, Paris admits that “if the page allowed, this whole island would be longer”. Although the map has no mathematical scale, Paris was probably just annoyed that the space of his rectangular manuscript codex prevented him adding more detail. This might be why he oriented it to the north: Britain is simply taller than wider, so fitted on his page better. Its aesthetic is also not quite what it seems. The elegant tinted washes used by Paris were fashionably quick and cheap alternatives to vivid designs of prevailing illumination. The composition probably started by using the outline of Britain from a contemporary world map, adding details from written itineraries and supplementing it with information gleaned from other manuscripts. The map’s current importance is intriguingly disproportionate to its original circulation. Matthew rarely left St Albans Abbey in Hertfordshire, and his manuscripts circulated among a relatively small, predominantly clerical elite. For us, the shape and outline are paramount; for Matthew and his readers, they were incidental. This is a physical and spiritual pilgrimage, connecting sacred sites from Durham to Dover, and onwards to the ultimate destination for all thirteenth-century Christians: Jerusalem.

Jerry Brotton is professor of Renaissance studies at Queen Mary University of London. His book History of World Mapping is published by Viking this year

Vidya Gastaldon on An Eye Miniature (anonymous), c.1750

Unknown

An Eye in a crescent shaped setting c.1800

Watercolour on ivory

1.2 x 2.2 cm

This eye is probably not God’s eye. It is looking at us on the side with a kind of coquetry which God wouldn’t normally use, and anyway God is probably looking at us in a much more frontal way. Definitely more practical when you have only one eye. So it has to be someone else; just another human eye, the idea of alterity, or even the reflection of your own eye in the infinite’s mirror. But who is smiling at us with such a big smile around the eye? How lovely and shiny are those tiny round Pacific pearls teeth? They could be the teeth of Lewis Carroll’s cat, hung in space, or those of a delicate geisha. But seriously, the only smile that can stand holding the infinite, along with your eye, and not swallow it, has to be the huge, the unique, the innénarable (that which cannot be told or spoken) cosmic smile.

Vidya Gastaldon is an artist based in Geneva. Call It What you Like is published by J.R.P. Ringier.

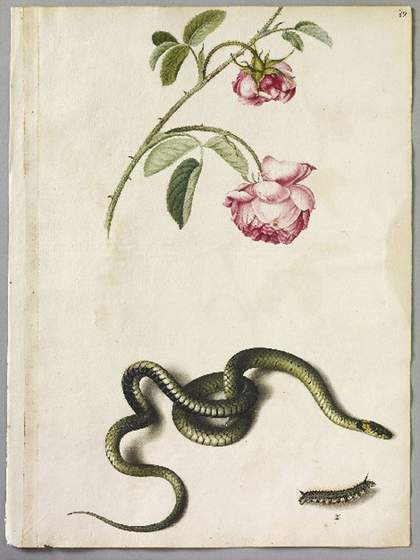

David Attenborough on Alexander Marshall (1620–1682)

Alexander Marshal

Unnanmed (cabbage rose): the English snake: Unnamed (Drinker moth caterpillar larva) c.1650–82

Watercolour on paper

35 x 25 cm

Artists over the centuries have painted flowers for several reasons. Some of the earliest were produced to illustrate the herbals – first manuscripts and later printed books that enabled people to identify the plants they needed as food or medicines. Their pictures were formal, almost diagrammatic, but they served their purpose well. In Holland during the seventeenth century artists depicted flowers in a very different way. They revelled in realism. They delineated every hair on a stem, every glistening dewdrop on a leaf, every spot of decay. For them, it seems, this was a way of showing off their extraordinary painterly skills.

But Alexander Marshal, an Englishman who was painting at around the same time, had quite different motives. His pictures were not intended to serve as identification guides or catalogues. Nor did he use them to demonstrate his skills. How can we know that? Because he declined to show them to the world at large. He revealed them only to his close friends.

Marshal had private means. He collected natural history objects, particularly insects. And he was a devoted gardener. In his time, great numbers of new species of flowering plants were arriving in Britain, not only from Europe, but also from the recently discovered Americas, and Marshal had a hand in importing them and supplying them to the great gardens of the country. And he painted them. Some of his sheets of drawings show garden plants arranged in ordered rows. Others, rather less formal, illustrate flowers from the countryside. And among them, drawn to a different scale but with an equal care, are pictures of his insects – a dragonfly, a caterpillar, a stag beetle – and his pets: a greyhound, an African parrot which he shows several times, gaudy macaws and a marmoset from South America.

He worked relatively slowly. At the end of his life, after 30 years of painting, he had accumulated only 159 sheets. People who knew of them tried to buy them, but he refused all offers. After his death his “florilegium”, as he called it, remained in his family for several generations. It is now in the Royal Collection. They still seem like private documents, un-showy and modest, yet close to perfection. If he did not paint his pictures to scale, nor to serve as a key to identification, nor even to demonstrate his ability to others, why did he paint? As you look at them, and delight in the skill with which he records every curl and contour of a petal and the way he mixes his flowers with other objects that he held dear, his motive, surely, cannot be in doubt.

Alexander Marshal painted for love.

David Attenborough is a broadcaster and naturalist. His documentary Frozen Planet will be on BBC One in the autumn.

Jennifer Higgie on Richard Dadd’s The Child’s Problem 1857

Richard Dadd

The Child’s Problem (1857)

Tate

What problem? Surely the title isn’t simply an allusion to a position on the chessboard considered easy enough to have been set by a child? The clues are as faint as old blood. There’s something ominous in this comfortable room – and not just in the boy’s dreadful eyes, or the possibility that, with his hand hovering over a chess piece, he is cheating. A knife lies at the centre of the watercolour – it’s painted, we must remember, by an artist who stabbed his father to death. (Is this the child’s problem?) There are three women here: an old one, asleep, while a younger one, trapped in stone, floats above her like a spectre. On the wall is a picture of a naked woman, her arms raised in supplication, which was used as a poster for the anti-slavery movement. It is reproduced here by an artist who was incarcerated for a crime for which he refused to accept guilt. (If the god Osiris tells you to do something, surely, Dadd reasoned, you must obey him.) Another kind of freedom is hinted at in the picture of the ship in full sail on the wall; it’s on its way to adventures now denied to an artist whose childhood was spent among the shipbuilders of Chatham and whose final, tragic adventure was precipitated by a long voyage. What is the child’s problem? Something is decidedly wrong; his eyes stare wildly, yet the women who surround him look away.

Jennifer Higgie is co-editor of frieze magazine and author of Bedlam, a novel inspired by a year in the life of Richard Dadd, published by Sternberg Press.

Silke Otto-Knapp on Samuel Palmer’s A Hilly Scene c.1826–8

Samuel Palmer painted an unusual number of nightscapes, which were often illuminated by a centrally positioned, exaggerated moon. Mainly using black ink or sepia, his paintings are based on observations of nature, but seem to aim for something far from a realistic depiction. While they refer to specific landscapes Palmer visited and observed, they achieve a visionary quality that seems very modern in its economy of means. A Hilly Scene is a small watercolour, symmetrically composed with two trees on either side that come together forming an arch just above a large sickle moon that illuminates the scene underneath. The hill mentioned in the title mirrors the shape of the moon like a round shadow. It ends abruptly in the middle of the picture with a horizontal line formed by the cornfield in the foreground, marking a dramatic divide between shadow and light. Palmer’s use of shapes and lines is bold; he depicts the leaves of the chestnut tree and the corn stalks with simple black outlines in exaggerated shapes. He combines this graphic approach to composition and shape with an unusual use of colour. The entire scene seems illuminated from within: the moon is the declared source of light, but it could not possibly produce this intensity of colour. Blues, yellows, oranges and greens seem to shine from beneath the darkness of the landscape, giving it an almost fantastical quality. The painting exists somewhere between the visionary aspirations of Palmer’s imagination and a realistic depiction of a familiar place.

Silke Otto-Knapp’s work is included in ‘Watercolour’.

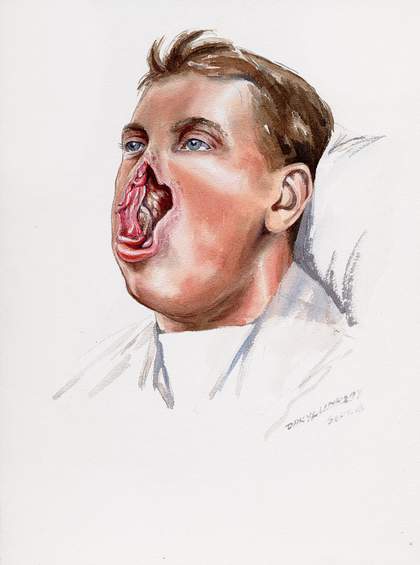

Matsui Fuyuko on Daryl Lindsay’s Potts 1918

Daryl Lindsay

Potts 1918

Watercolour on paper

29.1 x 23 cm

This watercolour, depicted realistically from a medical point of view, offers an insight into the painter’s knowledge of and interest in the human anatomy. From a work deeply rooted in psychology, one can also discover the true form of human beings.

In Japan during the Edo period (1603–1868) muzan-e (muzan, cruel, e, pictures) were seen as good luck, serving as a talisman to ward off evil spirits. At times they provided security for the house while the master was away, intimidating thugs and thieves with their horrid imagery. Although it is clear that this work was created for medical purposes, it is also possible to perceive it as a muzan painting. The completely objective approach towards the subject also arouses questions of ethics, social standards and preconceptions that we have towards the human face.

Matsui Fuyuko is an artist based in Tokyo.

Deanna Petherbridge on Paul Nash’s Wire 1918

Paul Nash

Wire 1918–19

Ink, chalk, watercolour on paper

73.5 x 86 cm

he poignancy of this desolate landscape, probably drawn during Nash’s period as official war artist in the First World War, doesn’t need to be underlined: the great bomb craters filled with sullen waters, possibly concealing rotten corpses; the pitiful paths up and down dunes that speak of some hidden human presence; the pall of smoke partly filling the sky; the imagined stench. We assume that it is winter from the degraded palette, but it could just be the winter of the soul – war allows no other season than that of desolation. What makes this painful watercolour so memorable is the blasted tree, a great ripped phallic symbol enmeshed with barbed wire. There is a long tradition in Western landscape art of decaying tree stumps as symbols of destroyed civilisations. In sixteenth and seventeenth-century landscapes such signs of decay signify renewal, but in this modern work about the horrors of war, rebirth has been suspended.

Deanna Petherbridge is an artist, writer and curator.

The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice is published by Yale.

David Musgrave on Hayley Tompkins’s Days Series 2007

Hayley Tompkins

Days Series 2007

Gouache on wood, spoon

3 x 13.1 x 2.1 cm

Hayley’s work is risky. Perhaps, you think, this is just a piece of stick with some silver gouache and photographic trimmings on it? Well, that’s exactly what it is. But at the same time it’s a perfect index of a set of lost decisions, the shadow of a sensibility formed by all the gratuitous complexity of contemporary life, a complexity it excludes or muffles. Hayley’s work consists of objects which are like questions about what objects are and what it’s possible to expect them to do; why something found or made has “rightness”, and why you might, on balance, keep it. Her watercolours are objects too. They aren’t pictures on a support, but supports bearing pigmentation. They’re objects that describe with diffidence the small negotiations of their making, rather than trying to dazzle you with layers of art historical erudition. That, for me, is what gives them their uncalculated ruggedness.

David Musgrave is an artist based in London