Joan Miró’s 1974 retrospective at the Grand Palais, Paris, included more than 300 works, half of which were paintings, bronzes, ceramics and tapestries made for the exhibition. The artist’s presence in the French capital provided him with a vehicle to reaffirm his earlier ‘assassination of painting’ and an international platform to denounce the repressive and authoritarian regime imposed by Francisco Franco. The series of five Burnt Canvases (Toiles brûlées) was a central component of the final room, where two were suspended high up so that both the fronts and backs could be seen. Miró had made these violent paintings in Tarragona from 4 to 31 December 1973, working with Josep Royo.

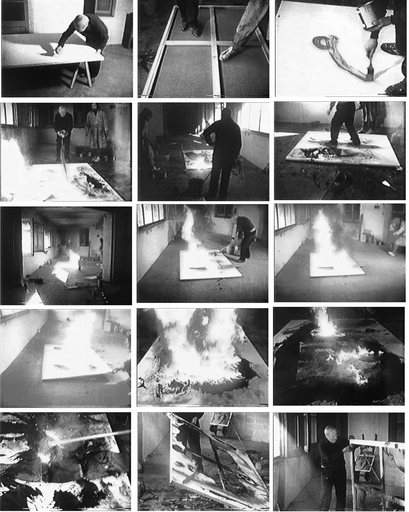

The multi-phase process was documented in a film by Francesc Català-Roca (Miró 73.Toiles brûlées, 1973). The canvases were first cut with a knife and punctured with sharp objects. Paint was applied and petrol poured on and ignited. Further paint was added and again burned, a wet mop being used for careful control and a blow torch for concentration on specific areas. Miró then walked on the painting with the surface face down, and a second phase of cutting with scissors was undertaken. He painted the surface with his fingers and punched holes in it. From behind, he cut away some of the burned fragments. A final stage included another application of paint and the nailing down of the burned fragments to the now revealed and scorched stretcher bars. Català-Roca’s film concluded with the works shown outdoors, where it was possible to look through the damaged sections to the natural landscape. Miró’s preparatory annotations referred to them as ‘burnt and lacerated canvases’, and listed four phases of work: ‘I: Pour colours, II: Cuts, III: Tear and hang it, IV: Black Spots.’ He reinforced the violent impulse by adding the comments ‘with rage’ and ‘improvise with rage”. In another note dated ‘12/IX/73’, Miró wrote: ‘Afterwards burn them and re-work them, the fact, gesture, moral of burning (?).’ Yet another note indicated the point of departure for the series in the violence of the period. In a press clipping titled ‘Hooliganism in Madrid’ (‘Gamberrada en Madrid’), a caption explains the news photo: ‘The windows of the principal façade of the Madrid Stock Exchange appear broken by stones, thrown by youths of both sexes, who hurled fireworks and cans of paint, as well as breaking the windows.’ Miró’s notes suggest this image was a source of inspiration: ‘Burn them [the canvases] partially. Throw stones at them and stab them to break them open. Cut them into pieces. Pour on pots of paint. Walk on top of them.’

In his Grand Palais catalogue essay, Jacques Dupin stressed that Miró “has chosen the violence of the fire as his accomplice and partner”. For critic Jeanine Warnod, Miró ’again questions painting which, according to him, is in “a state of decadence since the period of the caves”.’ As the artist told her, fire was also a material to be deployed: ‘The unforeseen, that is very seductive, as much in the firing of ceramic… or the lacerating of the burnt canvases in painting.’ Miró had used fire as a medium in his ceramics. He was further aware of how Yves Klein had painted with fire, how Manolo Millares treated his surfaces as a wound and how Lucio Fontana had lacerated and punctured the canvas. Indeed, through his friend René Metras, he had access to works by Millares and Fontana. Another critic, Jacques Michel, wrote how the Burnt Canvases series represented ‘rupture’ and ‘revolution’, adding: ‘It is another Miró which violates his canvases as if he shouted in rage against a world with which he does not live in peace. How otherwise to explain his latest canvases, lacerated, burned, perforated, which, hanging in the middle of the last room, summon memories of some tragic event?’

One of the most interesting articles regarding the Burnt Canvases was by Raoul-Jean Moulin in L’Humanité, the organ of the French Communist Party. For Moulin, these pictures were ‘the martyred body of painting’. Miró saw fire as productive, telling Moulin: ‘I love to work with fire… It destroys less than it transforms, it acts on what it burns with an inventive force which possesses magic.’ Moulin further argued for Miró’s social awareness: “The artist does not live in bliss. He is sensitive to the world, to the pulsation of his time, to the events which compel him to act.’ In conversation with Georges Raillard, Miró saw the series as a rejection of speculation: ‘I have burned these canvases as another way of saying shit to all of those people who say that these canvases are worth a fortune.’

Miró’s renewed ‘assassination of painting’ coincided with the sustained economic and political crisis of late Francoism. The 1960s were marked by detention, torture and executions. In 1963 the regime had executed the Marxist militant Julián Grimau. In 1966 students and the faculty of the University of Barcelona held a clandestine meeting at the Capuchin Monastery (Sarrià), where they issued the Manifesto For a Democratic University. Intellectuals and artists present included Antoni Tàpies, Oriol Bohigas, Albert Ràfols-Casamada, Joaquim Molas and Jordi Solé Tura. Many participants in the Capuchinada, including Tàpies, were later imprisoned. Miró, Jacques Dupin, Picasso and Michel Leiris donated works and manuscripts to help to pay the fines of those arrested. On 13 December 1970, 300 Catalan professionals, intellectuals and artists staged a meeting at the Monastery of Montserrat to denounce the Burgos trials (in which several members of ETA were condemned to death), torture and the death penalty. Tàpies was again present, along with Miró, Daniel Lelong, Dupin and Mario Vargas Llosa.

Stills from Francesc Català-Roca's film Miró73. Toiles Brûlées showing Miró creating his Burnt Canvases 1973

© Francesc Català-Roca Archive. COAC, Barcelona

Political violence on both the right and left marked these difficult years. On 20 December 1973 a group of ETA militants assassinated Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco in a bombing in Madrid. ETA’s action was undertaken as revenge for the trial of ten leaders of the outlawed trade union Comisiones Obreras. Although his Burnt Canvases were well underway at the time, Miró was sensitive to these events.

The Catalan anarchist and member of the anti-Francoist MIL (Movimiento Ibérico de Liberación), Salvador Puig Antich, had already been detained in September 1973, when a policeman had died. Though not implicated in Carrero Blanco’s death, Puig Antich was condemned to death and executed on 2 March 1974. During the preceding period of international appeals for clemency, Miró continued the intense preparations for the Paris retrospective and dedicated one of his major triptychs, Hope of a Condemned Man I-I-II (9 February 1974), to Puig Antich, whom he described as ‘the young Catalan antifascist’.

As the Burnt Canvases were made during Puig Antich’s custody, Miró sought to achieve a protest constructed within the practice of art. A political gesture could be relegated to anecdote, while an attack on painting represented a fundamental rejection of the reduction of art to elite culture and economic commodity. Alexandre Cirici, writing in 1970 of the artist’s ‘insurrection’, declared: ‘Miró raises a cry of protest’. Indeed, in his Burnt Canvases, his revolt situated art in the world, and beyond the confines of conventional institutional models.