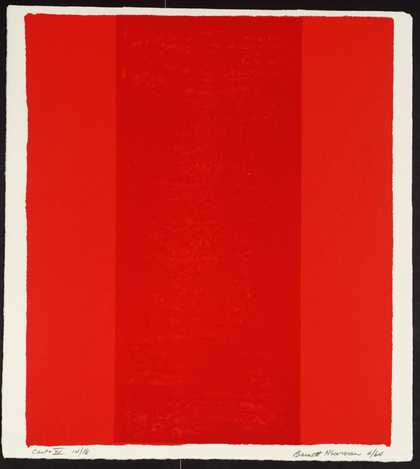

Caspar David Friedrich

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog 1818

Oil on canvas

98.4 x 74.8 cm

Courtesy Kunsthalle Hamburg

In the fertile climate of the contemporary art world the word sublime seems to be breeding prefixes: American-, anti-, architectural-, capitalist-, degenerate-, digital-, feminine-, gothic-, historical-, military-, negative-, nuclear-, oriental-, postmodern-, racial-, etc. Perhaps, like someone famous for being famous, sublime is just an empty word, one to which we can simply attach whatever meaning we need. But why should it have endured? After all, the term has a rather archaic ring, and, to make matters worse, in relation to the philosophy of art means something completely different from in ordinary usage, where sublime denotes the wonderful or perfect.

Pierre Huyghe

Still from One Million Kingdoms 2001

Video installation with sound, 7 min

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris © Pierre Huyghe

Etymologically, it comes from the Latin sublimis (elevated; lofty) derived from the preposition sub, meaning ‘up to’, and limen, the lintel of a doorway, or also perhaps from limes, meaning a boundary or limit. The word first came into vogue as a way of discussing new kinds of experiences sought by Romantic artists and generated by evocations of extreme aspects of nature – mountains, oceans, deserts – which produced emotions in the audience of a decidedly irrational and excessive kind, emotions seemingly aimed at evicting the human mind from its secure residence inside the House of Reason and throwing it into a boundless situation that was often frightening. Good painterly manifestations of this include Turner’s Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps 1812 and Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog 1818. But the term took on a new lease of life in the unlikely setting of 1940s New York City with the work of the Abstract Expressionists, especially in relation to Barnett Newman (who wrote an important short text on the subject called ‘The Sublime is Now’) and Mark Rothko. Here, the word was intended to signal what was characteristically different about American modern art. The sublime for these artists essentially meant an art possessing a depth and profundity European art failed to provide because, so they declared, it was still tied – in spite of such radical innovators as Picasso and Mondrian – to classical and outdated ideas about beauty and aesthetics.

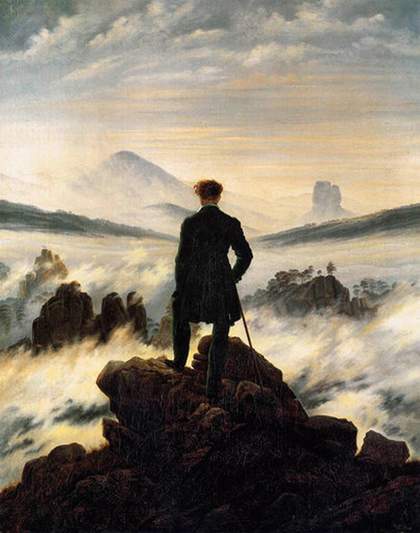

Walter de Maria

Two Lines and Three Circles on the Desert 1969

Film still

Courtesy Gagosian, London © Walter de Maria

In the event, however, the idea of the sublime didn’t take hold at that time. Instead, a largely formalist concept of the artwork became the dominant model within which to discuss the avant-garde of the 1950s and early 1960s. The goal of art was seen to be to pare a work down to a minimal visual language in order to establish its purity and also its resistance to the encroachments of kitschy popular culture. References to transcendence and the like were dismissed as being residually theological, or ways of thinking that had now been banished by a thoroughly modern and materialist aesthetic. Then, with Pop and Conceptual Art another shift occurred, one that served to challenge this, and so by the late 1970s the stage was set for a reassessment of the idea of the sublime.This time it came from continental Europe, and, in particular, from within the ranks of radical philosophers in France trying to come to terms with the failure of the political movements of the 1960s to respond adequately to the crisis in capitalism, and to bring about fundamental social change. They hoped, by seeking to understand aspects of human experience that seemed to lie beyond the controlling structures imposed by the status quo, to keep open a pathway leading to some kind of possibility of emancipation.

As a result of this renewed interest among postmodern thinkers and artists, we now have a rather confusing number of uses of the word sublime. In the book I have recently edited, The Sublime: Documents of Contemporary Art, I try to make sense of the situation, distinguishing five different ways in which the word is now broadly used. These are in relation to the problem of the unpresentable in art, and to the experiences of transcendence, terror, the uncanny and altered states of consciousness.There are also two main contexts for such discussions: nature and technology. What links such various perspectives, I think, is a desire to define a moment when social and psychological codes and structures no longer bind us, where we reach a sort of borderline at which rational thought comes to an end and we suddenly encounter something wholly and perturbingly other.

At the sublime’s core are experiences of self-transcendence that take us away from the forms of understanding provided by a secular, scientific and rationalist world view. Thus, discussions of the sublime in contemporary art can sometimes be covert or camouflaged devices for talking about the kinds of things that were once addressed by religious discourses and nevertheless seem to remain pertinent within an otherwise religiously sceptical and secularised world.

But often contemporary perspectives on the sublime reject traditional conceptions of a self, or a soul or spirit, seen as moving upwards towards some ineffable and essential thing or power. Instead, the contemporary sublime is mostly about immanent transcendence; that is, it is about a transformative experience understood as occurring within the here and now. What we make of this experience, what value we give it, can take us in two very different directions, however. One re-envisages the self as existing in the light of some unnameable revelation arising in a gap between, on the one hand, a dull and alienating reality, and on the other an unmediated awareness of life. In contrast, there is a far more pessimistic conclusion that can be drawn, one that ends up as a resigned sense of inadequacy, in which we are made aware of our emotional, cognitive, social and political failure when faced with all that so blatantly exceeds us.

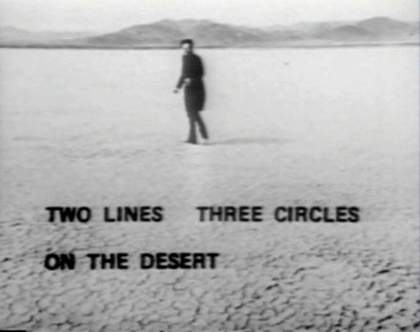

Olafur Eliasson

The Weather Project 2003

Installation view, Turbine Hall at Tate Modern

Photo: Tate Photography © Olafur Eliasson

Albert Speer

Light Dome 1937

130 anti-aircraft searchlights conceived for Hitler’s rally at the Zeppelinfeld in Nuremberg

Courtesy Bildarchiv Foto Marburg.

Photo: Lala Aufsberg

Ultimately, the concept of the sublime must pose more questions than it answers, and fortuitously Tate Modern has its very own laboratory of sorts, within which to address them: the Turbine Hall. Here, in a vast industrial architectural space that functions as a kind of man-made Gordale Scar (as depicted by the Romantic painter James Ward), artists are at regular intervals invited to tackle the sublime. Some succeed, while others do not. Three successes (at least for me) have been Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project 2003 – his extraordinary luminous man-made sun – Anish Kapoor’s huge maroon trumpet Marsyas 2002 and Miroslaw Balka’s dark container. Balka’s work, How It Is 2009, a huge steel structure with a vast dark chamber, captured perfectly the ‘terrific’ sublime as described by Edmund Burke in one of the founding texts on the subject, written in the mid-eighteenth century. Burke pinpointed a key aspect of the sublime as being the heightened and perversely exalted feeling we often get from being threatened by something beyond our control or understanding. We walk into the inky blankness of Balka’s giant container and quickly lose any comforting sense of place (at least when there are no mobile phone lights being turned on), something that is all the more remarkable as we are simultaneously aware of merely experiencing an artwork in a museum. But such, it seems, is the power of the sublime experience to destabilise and unnerve.

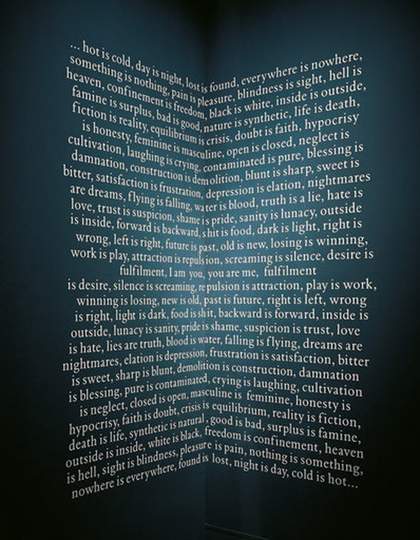

Douglas Gordon

Untitled (Text For Some Place Other Than This) 1996

Installation detail

Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven © Douglas Gordon

This is a kind of negative-sublime, one that lures us close to a point where, because we have entered a structureless and unsettling zone, we can feel the cold breath of what Wordsworth called the ‘blank abyss’. Such nameless and imageless emotions are also at the core of the recent site-specific work of Douglas Gordon, Pretty much every word written, spoken, heard, overheard from1989… 2010, in Tate Britain’s display Art and the Sublime. For Gordon, as for many other contemporary artists, it is as if the sublime can only be signalled through an enhanced sense of human insufficiency and anxiety, and at this extreme it merges with another key concept in contemporary art – the uncanny. Indeed, the American artist Mike Kelley has argued that the two terms are really synonymous: ‘I see the sublime as coming from the natural limitations of our knowledge: when we are confronted with something that’s beyond our limits of acceptability, or that threatens to expose some repressed thing, then we have this feeling of the uncanny.’

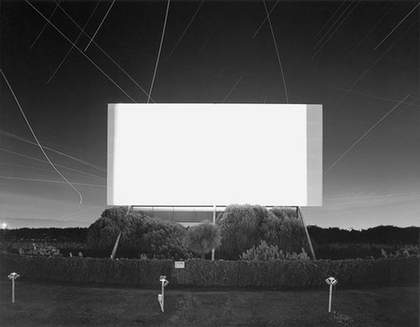

But Anish Kapoor’s monumental Marsyas, made of stretched PVC, managed to convey a more affirmative experience of the sublime – a kind of post-religious state of emotional transcendence in which, exactly because of the lack of ordered structures or codes, we feel a powerful sense of exaltation and release rather than fear. His work also serves to link discussions of the sublime to non- Western concepts. In an interview given several years ago, he declared that through the experience of void that is central to his art he sought to convey ‘a potential space, not a non-space’. Such ideas are closely allied to those of east Asian thought as it has come down to us through Taoism and Buddhism. In the ideas feeding the work of the Korean artist Lee Ufan, for example, or the Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto, a sense of void – of being on a borderline or edge where we can no longer codify experience – is considered a fundamental prerequisite for a deeper sense of reality, serving to mediate between being and nothingness, and communicating through a condition of absence a heightened awareness of the self. We find a similar commitment to an affirmative experience of sublime nothingness in the works of the American artist James Turrell, who uses light to dematerialise an environment and to propel the spectator into a state of sensory confusion that isn’t so much unsettling as ecstatic. Turrell, who is influenced by Quaker Christianity’s idea of divine light as well as by oriental concepts, declares that his work is involved in the ‘plumbing of visual space through the conscious act of moving, feeling out through the eyes’, and adds that the experience is ‘analogous to a physical journey of self as a flight of the soul through the planes’.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Union City Drive In, Union City 1993

Gelatin Silver Print

42.2 x 54 cm

Courtesy Pace Gallery © Hiroshi Sugimoto

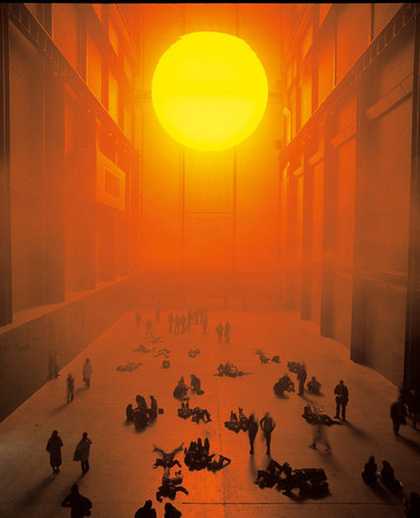

It seems that the most sublime artworks these days tend to be installations, and it is certainly proving harder and harder for painting, the traditional vessel for evoking visual sublimity, to elicit such effects. But the eclipsing of the sublime in painting is part of the logic of the sublime experience itself. For what once may have seemed sublime quickly becomes its opposite – the beautiful. Or, as the American critic Harold Rosenberg once wrote, it is the destiny of all art to eventually become craft. As the sublime deals with what lies on the other side of a cognitive and experiential borderline, it depends on an art that can convey the impression of almost not being art at all – that is, of something pushed beyond categories and structures. When Barnett Newman created his huge flat paintings sometimes consisting of one or two thin dividing ‘zips’, they did not look much like what even the most advanced analysts of art thought painting was. Now, however, they certainly do. The sublime edge has been blunted.

Gerhard Richter

Waldhaus 2004

Oil on canvas

142 x 98 cm

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © Gerhard Richter

One solution for painters has been to shift the medium into the field of photography. In the works of Gerhard Richter looking like blurred photographs, the German artist seems to touch on a new sense of the sublime as something that gets squeezed out as an intangible and ambiguous supplement in the gap between these two different but related media. It is the experience of an indeterminate yet fertile in-between state. His grandiose abstract works, on the other hand – or at least to me – seem merely to engage with the sublime in the more traditional and easily consoling sense of something that strives for the exalted effect. The Belgian painter Luc Tuymans, meanwhile, in his deliberately drab paintings derived from photographs, employs what might be called a language of the disappointed sublime (oh dear, another prefix), one that relates to Samuel Beckett’s devotion to the nobility of failure. Tuymans addresses thwarted transcendence, and yet at the same time behind his works we may sense that there hovers the ghost of some hope of transcendental release. It is no coincidence that many of Tuymans’s works often refer to Nazism,a movement in which sublime effects were exploited in order to inspire a nation to commit barbaric acts. Albert Speer’s Cathedrals of Light, constructed for the Nuremberg rallies, were frightening instances of the sublime in the hands of authoritarian politics, as today are the intricately orchestrated mass public displays of the North Koreans, which were the subject of a series of large-scale photographs by the German Andreas Gursky. These examples remind us that any discussion of the concept of the sublime should take into account its political implications.

Another negative context that makes an affirmative vision of the sublime problematic is the way the rhetoric of consumerist pseudo-sublimity is exploited within mass culture. Sublime effects are routinely produced to sell anything from automobiles to men’s aftershave. But for artists who have grown up deep within the dense technological forest of such a popular culture, the sublime often remains alluring, and it is not so much a question of looking for some way around these exploitations as of learning to live with them in a manner that still permits the exploration of self-transcendence.

Darren Almond

Night + Fog (Monchegorsk 8) 2007

Black and white bromide print

124.8 x 154.7 cm

Courtesy Jay Jopling/White Cube, London © Darren Almond

Mike Kelley

Dreadful Precipices (from the photo series The Sublime) 1984/1998

Courtesy the artist and Patrick Painter Inc. © Mike Kelley

Today it is technology rather than nature that provides us with our strongest sense of the sublime. While the legacy of the Land Artists of the 1970s, such as the Americans Robert Smithson or Walter de Maria, who expanded the frame of art into the vast open spaces of the mid-west, still makes itself felt, and contemporary photographers, such as Gursky or Darren Almond, continue to bring the awesomeness of nature into the art gallery via the medium of large-scale digital prints, it is not so much the desert, the stormy sea, or the mountain range that serve as subject matter for a contemporary sublimity as the mind-boggling power of science and the infinite spaces created by digitalisation. Indeed, any residual sense of nature comes thoroughly mediated. As the American artist Fred Tomaselli remarks of his childhood: ‘After hiking miles into the wilderness and discovering my first real waterfall, I immediately began looking for the pumps and conduit that make it work.’ A recent work by Eliasson seems to engage directly with just such cultural contagion and confusion, as it involved creating artificial waterfalls around New York City’s rivers. The magical effect they evinced suggested both a sense of something natural and at the same time thoroughly unnatural and man-made.

Today a vast new potential for transcending the limits of the physical body is available at the mere flick of a switch, leading some to talk of a new era of the digital sublime. The works of the French artist Philippe Parreno and his collaborators, for example, which were recently on display at Tate Modern, dive into the depths of virtual reality by exploring how contemporary subjectivity is distorted and augmented through plugging into the digital. The artists copyrighted a digital animation character in order to ‘set her free’ to ‘live’ in ways not constrained by the strict regulations imposed by the usual conventions of cyberspace. Perhaps it is indeed to this new world, beyond the limits of the physical body and of time and space, that the sublime experience is now migrating.