Few photographs have had anything like the impact of Eadweard Muybridge’s studies of human and animal locomotion, made in the 1870s and 1880s.They changed things forever and have come to symbolise modernity’s seismic and irreversible shifts in the understanding of vision, the living body, nature, science and art. So singular, so bold, so uncompromising was his project that historical time seems to split into two epochs. There is ‘before Muybridge’ and there is ‘after Muybridge’.

That is extraordinary enough, but it misses something even more profound: the impact of his work has never ceased. It still has the power to stop us in our tracks. When each one of us first encounters those sequences of ecstatic arrest do we not feel a change in our own internal order? Does not each one of us have a ‘before Muybridge’ and an ‘after’? Many nineteenth-century pioneers strike us as historical curiosities, but Muybridge trapped secrets so fundamental to modern experience that all subsequent generations have considered him theirs, if never in quite the same way. His influence on art confirms this. From Thomas Eakins using them as guides for paintings as early as 1879 to film-makers of this century, artists have been struck by the locomotion studies in myriad ways. Each finds in them a different revelation of what is contemporary.

Eadweard Muybridge

General view of experiment track, background and cameras, at Palo Alto, California 1881

Albumen silver print

13.9 x 22.9 cm

Courtesy Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

My own encounter came, as it does for most, in book form. In 1969 the publisher Dover issued cheap but good quality versions of Muybridge’s albums, triggering a renaissance of popular interest. They have never been out of print since. I came across them around 1977, one wet lunch hour in my school library. Children have voracious visual appetites and can race through entire shelves seeking satiation. My favourites were an actual size photo of Muhammad Ali’s fist (in Harold Evans’s Pictures on a Page) and the Muybridge books. The latter were the most vivid, uncompromising and authoritative images I had ever seen. They were also the most ambiguous, voyeuristic and obsessive. Who made them? Why? What were they for? How were you supposed to look at them? Settling the question of whether a galloping horse has all its feet off the ground could hardly justify this endless parade of beasts and men.

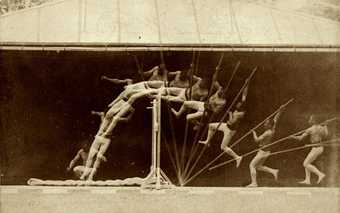

The reissued books chimed with the interest in all things serial that preoccupied vanguard artists of the 1960s. In December 1967 Artforum published ‘The Serial Attitude’, an essay by the artist Mel Bochner that placed Muybridge as the distant precursor of an art based on ‘a method, not a style’. In different ways Minimalist sculpture and music, Pop and Conceptualism were as openly concerned with the hypnotic precision of mathematical systems as with aesthetics. The more recent precursor, noted Bochner, was Marcel Duchamp. The essay reproduced Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) 1913 and highlighted its debt to another chronophotographer, the Frenchman Étienne-Jules Marey, whose multiple exposures overlaid the instants where Muybridge’s frames separated them.

Much earlier (1952) Life magazine had run a feature on Duchamp in which the artist re-enacted his painting for a multi-exposure portrait taken by Eliot Elisofon. A corny publicity stunt perhaps, but it was a key moment in the post-war rediscovery of Duchamp. By 1970, when MoMA New York presented ‘Information’ (the first international survey of conceptual art), his interests in chance, performance and mechanical repetition seemed to have permeated everything. To mark the show, Life reproduced Keith Arnatt’s Self Burial 1969, a deadpan photo-sequence of himself descending into the earth. Printed above the images was the declaration: ‘The content of my work is the strategy employed to ensure there is no content other than the strategy.’

Étienne Jules Marey

Chronophotographic study of man pole vaulting 1890

Albumen print

6.9 x 10.6 cm

Courtesy George Eastman House

Tight systems and repetitions tend to produce their own pathologies, especially in art. The experimental filmmaker, writer and occasional photographer Hollis Frampton knew this well. In his beautifully operatic essay ‘Fragments of a Tesseract’ (1973), the source of Muybridge’s compulsion to control and repeat is located in his own damaged psyche: having discovered his wife had given birth to a child by another man, he promptly tracked down the interloper and shot him. Muybridge was acquitted. He departed for South America to clear his mind with other projects, but returned to the locomotion studies with inexhaustible vigour. Perhaps he really was replaying the traumatic instants when he found he’d been cuckolded and when he exacted his revenge. Or perhaps that’s dollar-book Freud. Either way, Frampton’s own homage to Muybridge, the hilarious Sixteen Studies for Vegetable Locomotion (made with Marion Faller in 1975), points at the madness in any method pursued so single-mindedly.

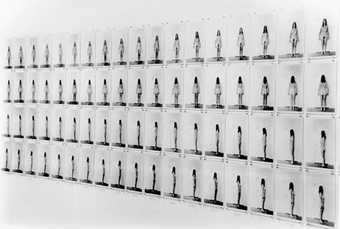

In ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’ (1967), Sol LeWitt proclaimed: ‘The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.’ Like Arnatt’s statement, it was typical of the terse, recalcitrant definitions of the time. This is only a recipe for austere anti-aestheticism if you think deployed machines or systems cannot produce anything of beauty, and if that’s the case, you are probably not going to ‘like’ Muybridge’s locomotion studies very much. LeWitt paid his respects to what he found fascinating in them with Muybridge II 1964. Through a peephole in a wooden box we see a photo of the torso of a seated nude woman. Across ten images we get progressively closer until only her abdomen fills our vision, moving from scientific objectivity, through intimacy to something a little too close. It is a hint at the sexual politics of looking that were expressed starkly in Eleanor Antin’s landmark Carving: A Traditional Sculpture 1972. A series of 148 pseudo-scientific, full-length photos of Antin’s own body were taken over 37 days, during which she dieted to lose ten pounds, “sculpting” herself towards an idealised image. At a formal level Carving is strikingly similar to Muybridge’s grids, but it highlights the ways the sexes are almost anxiously differentiated in his locomotion studies. Muybridge’s men run, leap, throw and tumble, while the women flee, act coy, nurture children and carry pails of water.

Eleanor Antin

Carving: A Traditional Sculpture 1972

Series of 148 photographs

79.2 x 518.2 cm

Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

© The Art Institute of Chicago

Thomas Eakins’s painting William Rush and his Model 1907–8 depicts one of America’s first sculptors at work. Rush had been commissioned to carve in wood a female figure as a symbol of the Schuykill River, which runs through Philadelphia. Eakins portrays Rush helping the model down from her podium. To paint the nude he deferred to one of Muybridge’s studies (Woman walking downstairs, throwing scarf over her shoulders, c.1885), changing it only a little to suit his purpose. In the final work the woman’s shadows do not match the man’s at all. Moreover, Eakins’s rendering of her is so graphic and lucid against the impressionistic background that the sculptor seems to he helping her right out of the painting. At first glance it is difficult to tell if this is technical naivety on Eakins’s part, or a brilliant meditation on desire and its tendency to hallucinate its object as something hyper-real and otherworldly.

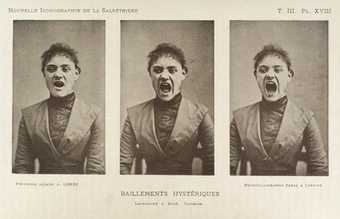

Albert Londe

Hysterical Yawning, as shown in Jean-Martin Charcot’s Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière c.1890

Photograph

Courtesy Wellcome Library, London

Within a few decades it was precisely this unnerving strangeness that was attracting Francis Bacon to Muybridge’s studies. Like Eakins, Bacon was less struck by their sequential nature than the mesmeric power of just one, plucked and scrutinised. But where Eakins saw in Muybridge a path towards idealisation, accuracy and knowledge, Bacon found the opposite: debasement, distortion and chaos. Both were right. There is a profound ambivalence lurking in the camera’s ability to make visible phenomena that are far beyond human perception. This ‘optical unconscious’, as Walter Benjamin cleverly named it, can bring enlightenment, but it can also bring uncertainty and even monstrosity. Bacon’s art of physical extremity and psychical trauma expresses the fear and loathing common to so much post-war existentialism, and his way of reworking Muybridge was crucial. The photo cut off from its natural order is rendered inexplicable, becoming a metaphor for the isolation of human beings from each other and from the world around them. Even the schematic frames Bacon painted in white to heighten the presence of his figures owe something to the cold abstraction of Muybridge’s metric grids. But just what are the spaces Bacon’s figures occupy? Torture chambers? Bedrooms? Stages? Theatre of enlightenment or theatre of cruelty? We rarely admit to ourselves how strange it must have felt to be one of Muybridge’s performing specimens, but I think such difficult empathy is what energises all of Bacon’s best paintings.

Nearly every book about the history of cinema offers Muybridge as one of its ‘parents’. We have all grown up with moving images, so it is difficult not to connect his instantaneous consecutive images with cinema. And while it is true that Muybridge himself devised a way of animating his photos (the Zoopraxiscope of 1879), he saw it as a novelty, far removed from the serious and noble project of stopping things. Chronophotography and cinematography give rise to incompatible yet intertwined ideas about the truth of images, time and motion. More importantly, they are aesthetically distinct forms. Nevertheless, the fact that a movie camera is just a still camera that takes photos in an unusual way can never be quite overcome, particularly if you are a film-maker. It is a fact you face all the time.

Tim Macmillan

Dead Horse 1998

Still frames

Time-slice video projection

Courtesy Time Slice® Films Ltd and Lux Distribution © Tim Macmillan

Perhaps this is why for decades filmmakers have wanted to set Muybridge in motion. In Migration, Hiraki Sawa’s video of 2003, the photos of humans and animals have been animated. They are walking in unison like toy figures through an empty house – across the worktops, over the carpet, along the window frames. We have all seen those figures brought to life somewhere or other, but Hiraki’s stroke of brilliance is to keep them the size they were in Muybridge’s books. They really do look as if they have finally stepped off the page to escape their petrified unrest.

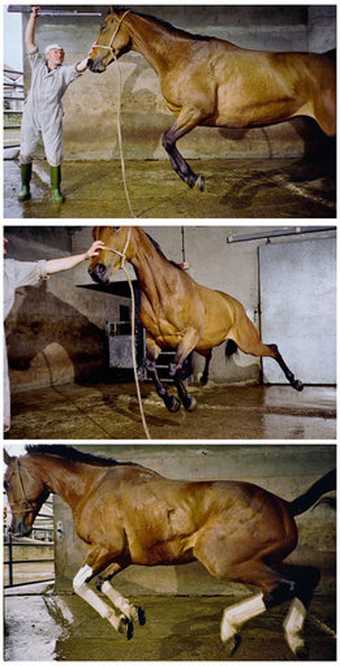

Dead Horse 1998, the video installation by Tim Macmillan, is the most visceral and perfect use of his Time-Slice® technique. At the moment of its execution in an abattoir, a horse is photographed simultaneously by an arcing bank of still cameras. The photos are then ordered into a filmic sequence. The result is a static world traversed by a moving gaze. Although it feels strikingly contemporary, the technology for doing this is as old as cinema, if not older. If Muybridge had fired all his cameras at once and animated the results via his Zoopraxiscope, we might have had a century of Time-Slice. That it appeared only relatively recently is less an anomaly than a sign of the fact that for any image form to come into being it must be first imagined or desired. Imagination and desire are historically grounded. Nobody wanted Time-Slice in 1879. The basic structures of photography and cinema have existed for a long time, but they have proved flexible enough to accommodate ever-newer conceptions of time, space, movement and stillness. That is why they are still with us rather than belonging to the nineteenth century. Macmillan’s video alludes to this historical delay with a clear reference back to the work of Muybridge’s very first studies of horses in motion.

One could go on listing the influences Muybridge has had on art. But those unexpected moments when we are reminded of his project are at least as telling. How do I account for the fact that I can never watch John Travolta’s bouncy-groovy stroll which kick-starts Saturday Night Fever (1977) without thinking of Muybridge’s studies of men walking? I guess I discovered both the same year, but that’s hardly an explanation.

Opening title sequence for Saturday Night Fever starring John Travolta 1977

© Paramount Pictures

It is the rhythm, the looping, loping rhythm. It is knowing that every walk is the same, yet every walk is unique (in fact, every step is unique). It is knowing that even walking is an expressive cultural act that cannot be reduced to science. It is staring like a voyeur at people in the form of objective documents while knowing deep down it is a performance entirely for you. It is the inseparability of looking, learning and pleasure. Aged ten, I doubt I ‘could tell by the way he used his walk he was a woman’s man (no time to talk)’. I just thought Travolta was great to watch. And that raw, almost visceral scopic satisfaction is at the heart of what I get from Muybridge.I am phrasing it simply here, but we know that anything to do with looking is complicated.

At the 1893 World’s Fair, Muybridge the showman delivered his lecture ‘The Science of Animal Locomotion in Its Relation to Design in Art’. He was booked to do it 300 times, but audiences were by then in thrall of cinema and they failed to show up. It would take a while to come around again to his work. The lecture title shouldn’t be blamed either. Although none too catchy, it was spot on, roping together the triumvirate of science, design and art without resolving the relation between them. It was precise and all too humanly ambiguous, just like the photographs. And that’s why they still look contemporary.