Rob Young on Paul Nash’s The Orchard 1914

Could such a thing as this fence really have existed before the First World War? Inked over pallid watercolour, it’s a modernist monstrosity, as if the architects of Guantánamo had stepped back a century to forge a manacle of chain-link and barbed wire around a strip of English woodland. And there’s a particular cruelty about a wire mesh: it affords a transparent view of what it holds you back from.

The Orchard 1914 (detail) Watercolour, ink and pencil on paper 57.5 x 48.2 cmPhotograph: Tate Photography © Tate

Yesterday I took a day-long hike over a forested mountain in south-western Norway; not a fence, barrier or “private” sign in sight. But where Scandinavia’s land is largely a common treasury, nature in Britain is defined by its exclusion zones, its boundaries. Nash’s fence – and the birds cautiously shadowing its perimeter – stirs folk memories: Winstanley’s Diggers evicted from St George’s Hill; the 1760 Inclosures Act; the Highland Clearances; even the corrugated-iron barricade around the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival, on which someone whitewashed the immortal phrase, “Entrance is Everywhere”, before it was torn down. More pertinent to Nash’s lifetime, it’s a reminder that it was the British, during the Boer War of 1899–1902, who created the first concentration camps.

Barriers, dividing lines, slice through the heart of the British experience. Nash’s orchard is Paradise Enclosed. Or is it? For the forbidden apple trees are winter-barren. Are we really on the wrong side of the fence? Is it really so desirable, that managed Eden over there?

The Orchard was purchased in 1975.

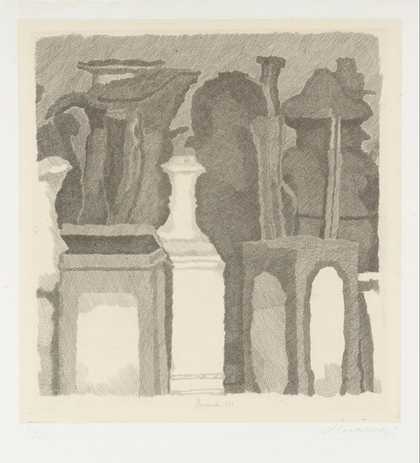

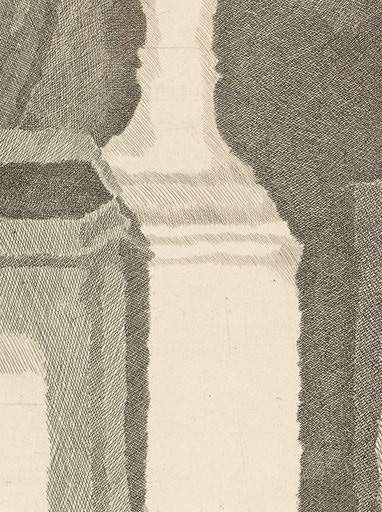

Giorgio Morandi

Still Life with Very Fine Hatching (1933)

Tate

Giorgio Morandi Still Life with Very Fine Hatching 1933 (detail) Etching on paper 24.8 x 23.8 cmTate Photography © Tate

Alice Channer on Giorgio Morandi’s Still Life with Very Fine Hatching 1933

In the middle of Morandi’s claustrophobic print he has left a hole for me to look through. This is odd, because the moment that I fall through into the image, I realise that the gap I have fallen through is itself an object. I know this because it has an outline. This edge defines a shape that is familiar to me; I have similar bottles in my kitchen. But the edge of this one is humming and fizzing, jumping awkwardly along the outline of the object.

Straight, cross-hatched lines hold the crowd of pots, bottles, jugs and vases on to the paper. These objects are stretched vertically. By flattening them in this way, the image vibrates with concentrated energy. I am looking at Morandi’s print on a computer screen, and it feels strangely compatible with virtual space. His objects are just about to dematerialise into each other, the space around them and the screen. His crowd have their backs to me, and it seems that they are held together only for a moment. If I break my stare, they will move away.

All of this is achieved with the intimate and economical means of lines on paper. What I want from art is to feel another person thinking, and when I look at, with and through Morandi’s image, I feel that I am looking through him, with his eyes, at objects I had assumed a familiarity with.

Still Life with Very Fine Hatching was presented by Señor and Señora Jose Luis Plaza in 1979. The Prints and Drawings Room at Tate Britain is open to visitors by appointment.

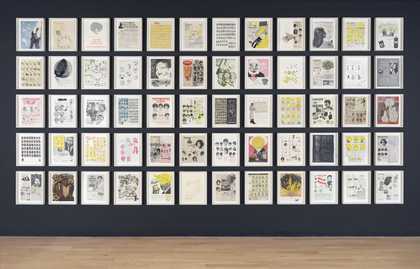

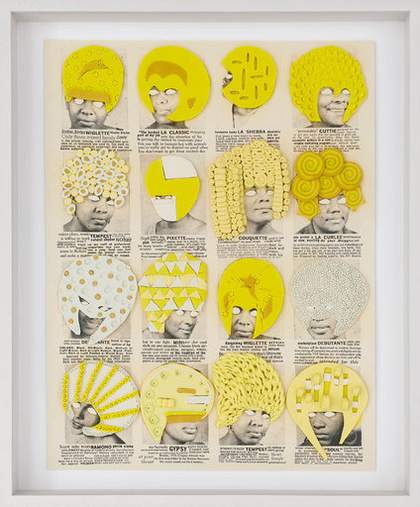

Ellen Gallagher

DeLuxe (2004–5)

Tate

Ellen Gallagher Deluxe 2004–5 (detail) Mixed media 60 frames, 38.9 x 32 cm eachTate Photography © Tate

Leyla Tahir on Ellen Gallagher’s DeLuxe 2004–5

I remember it so clearly: the first time I “slicked” my hair. It was the afternoon of the year-seven Christmas party. There I stood, in my form room, amidst the rest of my class – a rabble of eleven-year-old girls, lost to a cloud of sugar-sweet sprays, combing and primping themselves in the hope that one of them would become the belle of the Christmas disco. Outfits and hairstyles had been planned en masse, months in advance, to ensure that class 7T could execute the perfect march across the playground and claim their spot at the top of the year’s style ranks. We were about to leave when the then most popular girl in my form strutted over to me, and, clearly unimpressed with my regulation side parting and single plait, declared that she was going to “slick down” my hair. Full of trepidation, I sat down to an audience of my entire form, and waited as she took a bristle brush and a bottle of Luster’s Pink Lotion to my hair. I waited.

I emerged a slicked vision, with a ponytail high on my head, perfectly sleek from root to end, which she had braided into a tighter plait than I had ever managed. When I look at Wiglette from Ellen Gallagher’s DeLuxe (2004), I can’t help but envisage that troop of eleven-year-olds marching across the playground with slicked hairstyles, no two the same – and mostly, how excited I was to be one of them.

DeLuxe was purchased in 2006.

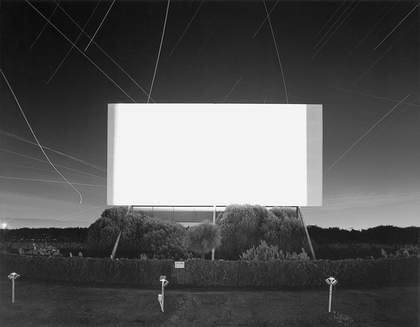

Hiroshi SugimotoRosecrans Drive-In, Paramount 1933Photograph on paper 42.4 x 54.3 cm

Hiroshi Sugimoto Rosecrans Drive-In, Paramount 1933 (detail) Photograph on paper 42.4 x 54.3 cmTate Photography © Tate

Rabih Mroué on Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Rosecrans Drive-in, Paramount 1993

I wonder if I ever saw that white; a white with neither past, nor present, nor future. No beginning. No end. No timeline; as if a life in a whole.I wonder if I ever saw his white in their life(s).Glances that became my own.

When I blacked out that night I saw that white.When the needle pierced my skin I saw that white.When I followed the white line I saw that white.When I saw only white in your eyes I saw that white.When I saw my veins turn blue I saw that white.When I thought I died I saw that white.When I saw you on that big screen screaming for me to get you out I saw that white.When the smoke filled the room I saw that white.When there was no way out I saw that white.When the city burns I see that white.When I will have our fetus in my hands I will see that white.When I fell in the shower I saw that white.When I lost my passport I saw that white.When you broke my nose I saw that white.When I saw you lying in my bed I saw that white.When you told me you died I saw that white.On judgment day I saw that white.On the seventh day in my tiny cell I saw that white.On the first day of spring I will see that white.

Rosecrans Drive-in, Paramount was purchased in 1994 and is on view at Tate Modern.