When Gauguin arrived in Tahiti for the first time, in June 1891, he had his hair down to his shoulders, wore a cockade with red fur, and his clothes were flamboyant and provocative. He had dressed like this ever since he had given up his career on the Stock Exchange in Paris. The indigenous people of Papeete were surprised at his appearance and believed he was a mahu, a rare species among the Europeans in Polynesia. The colonists explained to the painter that, in the Maori tongue, the mahu was a man-woman, a type that had existed from time immemorial in the cultures of the Pacific, but which had been demonised and banned by common consent by both Catholic and Protestant missionaries, engaged in a fierce battle to indoctrinate the native peoples, during the intense period of colonisation in the mid-nineteenth century.

However, it was proved well-nigh impossible to root out the mahu from indigenous society. Concealed in urban settlements, the mahu survived in the villages and even in the cities, and re-emerged when official hostility and persecution abated. Proof of this fact can be found in Gauguin’s paintings in the nine years that he spent in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands, which are full of human beings of uncertain gender who share equally masculine and feminine attributes with a naturalness and openness that is similar to the way in which his characters display their nakedness, merge with natural order or indulge in leisure.

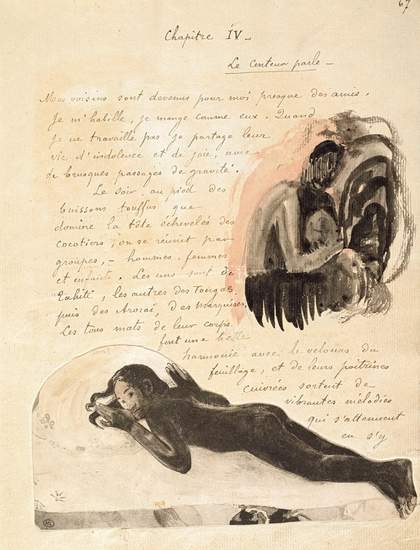

Page from Chapter IV of Paul Gauguin’s Noa Noa, Voyage à Tahiti

Prints, photograph, pen and ink and watercolour illustrations

Courtesy Museé du Louvre, Paris

© RMN (Museé d'Orsay/ Herve Lewandowski)

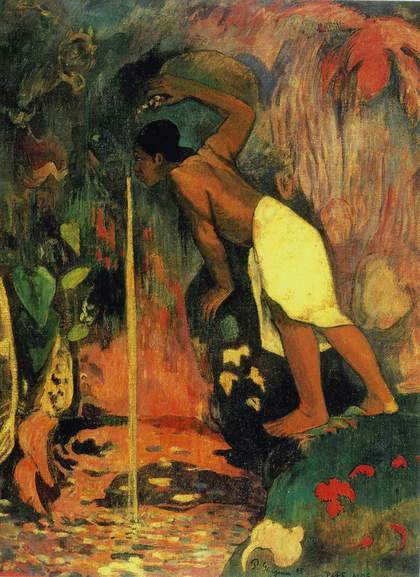

In his book of fantasised memoirs, Noa Noa, Gauguin relates a quasi-homosexual experience that he said inspired his painting Pape Moe (Mysterious Water) 1893, in which an androgynous young person is bending over to drink from a forest waterfall. In fact Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings would be very different and would seem much more arbitrary, without the strong presence of the mahu in the indigenous community that he was so close to. They are the raw material, the secret root, of his women with the solid thighs and broad shoulders, who stand firmly on the ground, and of his effeminate young men, in languid poses who seem to exhibit themselves as they stretch out to pick fruit from the trees, and who adorn their long hair with diadems of flowers. It is true that he invented these unmistakable characters; but he based them on a human reality about which, curiously for a man so loquacious, he always maintained a stubborn reserve.

It is risky to translate mahu as homosexual because, even in the most permissive societies of our age, homosexuality is still surrounded by prejudice and discrimination. Such prejudices did not exist among the Polynesians before the emissaries of Christian Europe censored a practice that, before their arrival, was recognised and universally accepted as a legitimate variant of human diversity. The extraordinary sexual freedom of the Maoris of the islands has been subject to countless studies, testimonies and caricatures ever since the first European ships reached these islands of paradisiacal beauty. Only now that western society has gradually made sufficient advances to allow similar sexual freedom and tolerance to that enjoyed by Polynesian cultures can we realise how civilised and lucid these small Pacific Maori communities were, at a time when the powerful West was still mired in the savagery of prejudice and intolerance. It was not just a question of sexual freedom; there was also the widespread practice among native communities of adopting orphaned or abandoned children, a custom that is still maintained. (Mr Tetuani of Mataiea, where Gauguin lived for several months, had 25 adopted children.)

The mahu might be a practising homosexual or remain chaste, like a girl making a vow of chastity. What defines them is not how or with whom they make love, but that, having been born with the sexual organs of a man, they have opted for femininity, usually from childhood, and that, helped by their family and community, they have become women, in their way of dressing, walking, talking, singing, working and often, but clearly not necessarily, of making love.

One of the reasons why, despite the prohibitions of the Churches, the mahu survived in Maori society during the nineteenth century was that they could count on the hidden complicity of the European colonists. They hired mahus to work as domestic servants – cooks, child-minders, launderers, etc – because for these household tasks the mahus were generally competent and, according to public opinion, ‘irreplaceable’. And in certain songs, dances and public ceremonies the Mahus were also indispensible, because they are strictly for them, traditional expressions of what we might call that third sex, that are markedly different from male and female expressions.

Is it true that today, unlike what happened in earlier Polynesian society, 90 per cent of mahus are of humble origin, and that there is something like a relationship of cause and effect between the mahu and the poorest and most marginal sectors of indigenous society? (I hasten to add the proviso that ‘poverty’ and ‘marginality’ are concepts that, in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands, bear little relationship to the extremes of injustice and inhumanity that these words express, for example, in Latin America.) It must be the case, since I was given the information by a sociologist from the University of Papeete, who has studied Maori society for many years. He also told me that whereas in the past it was often the case that if a family had a number of boys, their own parents would decide to educate one of the boys as a girl, today nobody is a mahu through parental imposition, but through their own free choice.

In any event, even though the majority of the mahus are of humble origin, there are a number among the native middle classes of the islands. I have seen them, for example, in university lecture halls, mingling with the other students, as customers or employees in restaurants or cafés, and in the Protestant and Catholic services on Sundays, dressed up in beautiful clothes and headgear, without attracting any impertinent glances apart from mine.

I confess my admiration for the absolute normality with which I have seen the mahus move around, from the streets, hotels and offices of modern Papeete to remote rural areas in Atuona, on the island of Hiva Oa, or on the Marquesas. The cook in the hotel I stayed in on Atuona was a mahu called Teriki who told me that she had realised around eleven or twelve that she wanted to be a woman. Her parents did not place any obstacles in her way; quite the reverse, they helped her from the outset, dressing her as a woman. She assured me that she had never been ill-treated or ridiculed by anyone on Atuona, where she and the other mahus – ten per cent of the male population, she assures me – lead a normal life. It’s true that they had some difficulties at first with the friendly Father Labró of the Catholic mission, but Teriki and other mahus on the island explained their case at length, and from then on ‘the parish priest accepted us’.

Paul Gauguin

Pape moe 1893

Oil on canvas

99 x 65 cm

Courtesy Foundation EG Bührle. Private collection, Switzerland

However, a curious character that I got to know on Papeete, called Cerdan Claude, assured me that, contrary to appearances and the evidence of my own eyes, the mahus were not widely accepted in Polynesian society. According to him, modernity has also brought machismo and homophobia to Polynesia, above all at night, when it was not unusual to find gangs of thugs bursting into the prostitute district around the port of Papeete looking for mahus to harass and beat up. Cerdan Claude is 60, and is gaunt and mysterious like a character out of Conrad. He was born in a Foreign Legion camp in Algeria, but he has never been a legionnaire. He has travelled the world, was once a boxer, has spent more than 30 years in Tahiti and now writes novels. His latest is a documentary novel on the world of rae rae, a word that I thought synonymous with mahu, but he assures me that between the two terms is a ‘metaphysical distance’. His long explanation of the difference leaves me confused. I finally deduce that while the mahu is the man-woman with traditional roots in Polynesian society, the Tahitian rae rae is its modern, urban expression, having more in common with the snipped and tucked drag queens of the west, with their hormone and silicone injections, than with the delicate cultural, psychological and social re-creation that is the mahu of the Maori tradition. The mahu is an integral part of society, while the rae rae lives on its margins. Cerdan Claude seems to know very well the nocturnal world of prostitution inhabited by the rae rae, a world in which he moves freely; he adopts a beneficent, rather paternal attitude towards them. They tell him about their sorrows and desires and he gives them advice on how ‘to deal with the problems of life’: he says it with such conviction that I believe him.

The Piano Bar in Papeete, where Cerdan Claude takes me one night, is an enormous, smoky discotheque, where the rae rae and heterosexual couples socialise in perfect harmony. They mingle all the time. It is not easy to detect the borders that separate the sexes – my impression is that very little or nothing separates them – at least to my layman’s eye. Cerdan Claude, by contrast, has a very sharp eye, and knows everyone by name. The rae rae come, one after the other, to greet him and kiss him on the cheek, and he receives them like a kindly grandfather. He introduces me to everyone and encourages them to talk about their lives and have their photograph taken by my daughter Morgana, something which they are delighted to do, brimming over with good humour and childish curiosity. Anne, the son of a New Zealand man and a Tahitian woman, is a beautiful, willowy girl who, she says, had difficulties with her parents when, as a boy she started to dress as a girl. But now she gets on very well with them and they do not object to her sexual orientation. It is difficult to imagine that this smiling young woman was once a man. But she was, and still is, in part, as she tells me with great charm and no hint of vulgarity. She has been under the surgeon’s knife, which retouched her nose and implanted the upright breast that she displays, but she has still to replace her phallus and testicles with an artificial vagina, because the operation is very expensive. She is saving and will have it done. She has just spent a couple of years in Paris, where she got some good modelling jobs, but the violence in the city, where one night, an Arab threatened her with a knife, and the cold made her return to warm and peaceful Polynesia. When she leaves us, the boys at the Piano Bar swarm around her like flies, asking her to dance. I heard her utter this patriotic phrase, the most surprising of the night and perhaps of my entire rapid visit to Tahiti: ‘It’s a thousand times better to be a prostitute in Papeete than a model in Paris.’