A little blue plaque at 60 Parkhill Road, London NW3, is all that remains to remind us of Piet Mondrian’s two years in London. Mondrian had travelled from Paris (where he had been living since 1912) to England in September 1938, aged 66, accompanied by fellow artist Winifred Nicholson. He came primarily to escape the looming threat of war in Europe, but also because he regarded the art scene in Paris as “a stalemate”. He viewed London as a useful staging post on the way to New York, and never guessed he would end up staying for so long.

The Russian émigré sculptor Naum Gabo had booked him into a hotel – the relatively plush Ormonde Hotel in Belsize Park – where he stayed for two weeks, until Ben Nicholson found him a room on the ground floor in a shared house nearby in Hampstead. Nicholson’s own studio was just below Mondrian’s window, and his home in the Mall Studios with his second wife Barbara Hepworth and their young triplets was just around the corner. A community of artists lived in the area, including Gabo and his wife Miriam, Henry Moore, Paul Nash and John Cecil Stephenson, as well as a host of critics, writers, collectors and enthusiasts – among them Herbert Read, Hartley Ramsden and Margot Eates. Mondrian would meet many of them, though most, including Nicholson and Hepworth, would leave London at the outbreak of the Second World War.

Nicholson had first met Mondrian in Paris in 1933. He took Hepworth to visit his studio in Montparnasse and the artist had regularly corresponded with both since then. They became good friends and a great support to the Dutch painter – Nicholson would secure sales of Mondrian’s pictures to various friends and colleagues – and it was viewed that his arrival was a sign that London was now an important centre for the avant-garde.

Mondrian quickly transformed his new home. He had his few possessions that had been sent from Paris – a trunk filled with personal documents, a suitcase and his gramophone, as well as some canvases. He bought a couple of drum-shaped stools from Camden market and painted them white, and also accepted gifts of furniture and clothes (including a bed from Nicholson and a much appreciated pair of slippers from Gabo). He got his landlord to paint the brown walls a brilliant white, “with the odd patch of red”, and then placed his canvases around the room – as if he were creating a 3-D version of his paintings.“His wonderful squares of primary colours climbed up the walls,” remembered Hepworth. Those who visited his studio would not forget the experience. Thirty years later, Nicholson recounted: “The effect of entering his room on a foggy Hampstead night was indeed something.” Sadly, no photographs of this space exist.

The Dutchman shared the building with several other lodgers, including office workers, businessmen and a young police constable and his wife. Although he was hardly aware of them, he did register that “sometime[s] the house has a smell of delicious roast beef or fish”. He preferred to keep his distance, washing in a basin in his room rather than using the shared bathroom, and doing his own cooking on a tiny stove. At the time, Mondrian was a determined follower of the Hay diet, a strict food regime that meant no mixing of protein and starches. His London friends teased him about his meagre ration of carrots and raisins, but for him it was not a diet, but “scientific dietetics”. In his copy of the Hay manual, the pages are heavily annotated with lists of possible foods, yet in one corner of a page he enigmatically added the words “mince pie”.

This quasi-scientific approach extended, in some respects, to his painting. In his new studio he laboured on new pictures or ones that he had started in Paris, covering parts of the canvases with cut-out pieces of newspaper to work out his compositions. He also did preparatory pencil sketches on old cigarette packets and pieces of card. Contrary to what has been generally assumed, Mondrian was “greatly influenced by these different surroundings” of London. He was impressed by the empty streets that were “so wide and spread out”, and, for him, ‘in comparison, Paris seems like a toy city”. He liked the imposing residential blocks in Belsize Park and Hampstead, as well as the grand architectural tourist sites such as the Tower of London, the Houses of Parliament and St Paul’s Cathedral. He sent postcards of these places to his younger brother Carel, telling him excitedly of his progress in his new city.

Mondrian also sent his brother a whole series of uncharacteristically light-hearted postcards of Disney’s Snow White (which he had seen with him in Paris in early 1938). In a tone that he doesn’t reveal anywhere else, his letters are full of parallels with characters in the film and people who helped him in his new home. In one he writes how the “landlord has had my room cleaned by Snow White and the squirrel has whitewashed the walls with his tail”. He signs the card “Sleepy” (he calls Carel “Sneezy”). In another, he writes that the “dwarves don’t have enough time to help me themselves, but send squirrels and birds” – a reference to the artists who had befriended him.

He never mentioned his quirky passion for Snow White to his London friends, but had, as he wrote, “a record with the music of the dwarfs on it, and [I] quite often play it”. And he told his brother he had seen the plaster versions (garden gnomes) in the London shops. (He was less impressed by Pinnochio when he saw it in spring 1940.)

These jovial, colourful figures were not the only visual interest that Mondrian took beyond his painting. According to his new friends, Nicholson’s lawyer Robin Ody and his girlfriend Joan, he had a fascination for women’s shoes – the brighter the colour, the better – though he didn’t explain why. He and the Odys would spend many evenings together, during which she regularly darned his socks. Joan remembered that he was a “dear old man… a wonderful person to know, exciting to talk with”. Mondrian would be a witness at their wedding in July 1940 and gave the couple one of his paintings as a wedding present (now in the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art).

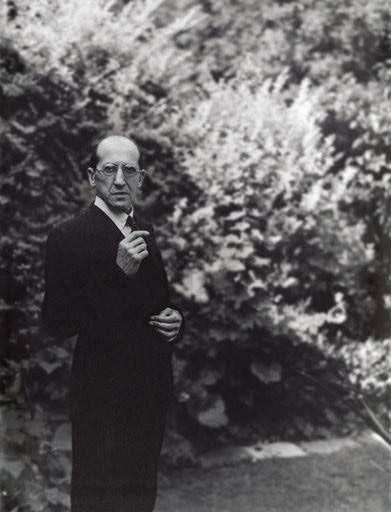

Piet Mondrian photographed in a Hampstead garden by John Cecil Stephenson 1939

Estate of John Cecil Stephenson/Tate Archive

Mondrian’s own personal life remained notoriously private, but Theo van Doesburg’s wife Nelly, who had known him for many years, remembered him as far from being a prude, and as someone who would “interrupt any type of conversation in order to comment on… the physical attractiveness of some admired example of the opposite sex”. She thought that his ideal wife would be a youthful love goddess – “a Mae West in crinolines”. It never happened for him, though he had been engaged briefly when he was 37, but Mondrian certainly enjoyed the company of women in London. As the legendary New York art dealer Sidney Janis put it: “Girls floated around him.” He went shopping for painter’s smocks with Naum Gabo’s wife Miriam and danced with Peggy Guggenheim and Virginia Pevsner in the London jazz clubs. His love of jazz and dancing was well known, but Miriam recalled that he “was a terrible dancer… Virginia hated it and I hated it, we had to take turns dancing with him”.

Not everyone immediately warmed to the artist. He was, as Gabo described, “intrinsically warm, but outwardly cold”, which could give the wrong impression. The collector and peace activist Margaret Gardiner remembered seeing him at a Hampstead party and noticed how he “stood very stiffly, with straight arms pressed close to his sides as though defending himself against some dangerous intrusion. [He was] a Dutch puritan, akin to the stern Arnolfini”.

Mondrian preferred discussing art primarily with his male friends, his closest being the artist John Cecil Stephenson, who lived in the Mall Studios. Stephenson had featured in the influential book Circle: An International Surveyof Constructivist Art, edited by Gabo, Nicholson and Leslie Martin, and was a keen proponent of abstraction. As well as regularly meeting and talking about art with Mondrian, he would often drive him into town to visit the London sights and exhibitions. He also took the only known photographic evidence of the Dutchman’s time in London – a stiff-looking portrait of him standing in Stephenson’s back garden.

Mondrian was, of course, already a well-known artist, and it was only a matter of months before he was being asked to show his work in London galleries. The first to approach him was the Belgian Surrealist E.L.T. Mesens, who included two of his new paintings in the curious group exhibition Living Art in England, in early 1939, somewhat incongruously alongside John Heartfield, John Tunnard, Paul Nash and John Piper. Several months later he displayed similar works in Abstract and Concrete Art, organised by Peggy Guggenheim in her short-lived Guggenheim Jeune gallery.

These paintings demonstrated subtle shifts from his early Paris works. The characteristic black lines that crisscrossed the canvas became more intense – and closer together. Was this the effect of living in London? While Mondrian never described his pictures as going through a distinct “London phase”, the American painter Charmion von Wiegand (who befriended the artist in New York) remarked how Mondrian referred to them as his “Gothic paintings”. Ever the self-critic, Wiegand said, “he thought there was too much emphasis on verticality”.

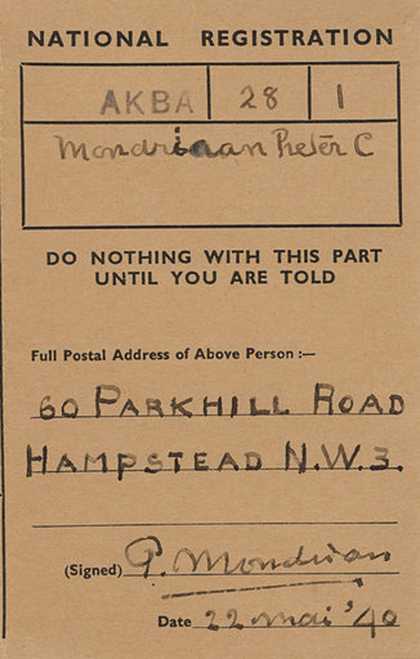

Detail of Mondrian's British National Registration document 1940

Coutesy Yale University Library

Despite his painting progress, Joan Ody remembered that the artist was, above all else, terrified of a Nazi invasion. He had good cause. Two of his canvases had been shown in Hitler’s Degenerate Art exhibition in 1937, and he was effectively on a blacklist. For Mondrian, his art was his life. He wrote to Hepworth (who was now safely living in Cornwall): “The great danger for us is about our work; might the Nazis come in, what then?” He told Stephenson, who was one of the few of his circle who remained in London, that he “expects himself a prisoner”. The war increasingly encroached on him. The German invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940 made him worry over the “sad fate of Holland and the situation of my friends and two brothers there”. He was further shocked by the fall of Paris one month later, and wrote to Winifred Nicholson saying that the war meant he could no longer paint.

Keen to leave London, in the summer of 1940 he managed to arrange an American visa and a passage to New York. However, his progress was hampered by the start of the Blitz on 7 September. On one evening a bomb very nearly killed him as he sat in his bedroom. Luckily, the blackout shutters that he had made were closed and he avoided the full force of the glass, escaping with only “dust in an eye”. He decamped to a hotel for another anxious two weeks, where amid the heavy bombing he would sit “all night dressed in an armchair in the basement”.

Finally, his time to leave arrived. Robin Ody drove him the long journey up to Liverpool where he boarded his ship. Even here, however, he was not safe from the enemy, with the vessel narrowly escaping a night attack from the air over the Atlantic. Several weeks later he arrived in New York City in a physically fragile state. It was the city that he had waited all his life to see, and here he would go on to paint perhaps his most famous canvas, Broadway Boogie Woogie 1942–1943, building on the work that he had started in London.