Few artists are as closely associated with Cornwall as Peter Lanyon (1918–1964). No article, book or exhibition fails to list the core biographical facts that tie him to West Penwith, the duchy’s westernmost tip. Born, raised and buried there, he is the lone native among the major figures of that largely uncontested category known as the post-war St Ives School. And in truth so many of Lanyon’s own statements and works carry references to Cornwall that the approach is more than justified. Yet Cornwall was not a simple or stable thing for Lanyon, nor paradoxically was it the only place that fed into his paintings of it. It may seem wilful, even perverse, to explore Lanyon’s identification with Cornwall by looking towards Italy, but there are few truisms more true than that which says one must leave home in order to find it.

Peter Lanyon was 25 when he first went to Italy in December 1943. He was a flight mechanic in the RAF and stayed for exactly two years, in which time he learned Italian and travelled the southern provinces, drawing, painting, taking photographs and making constructions when he could. After the war he returned three times: in 1950 with his wife, for a month, in the winter of 1953 for four months and in 1957 for about a week.

Before his arrival in Italy in 1943, Lanyon had found military life difficult. He was often lonely and homesick, and until about the end of 1944 he continued to be. But as the war eased, his spirits rose. In 1945 he was transferred to the RAF’s educational department, where he ran an art education programme for servicemen. It thrived and Lanyon, who had a strong sense of the moral and social worth of art, saw within it a model that might be replicated in community centres throughout Britain, including St Ives.

Peter Lanyon

The Yellow Runner 1946

Oil on board

44.5 x 58.5 cm

Courtesy Abbit Hall Art Gallery and the Lakeland Arts Trust © The estate of Peter Lanyon.

This hope was part of a grander purpose. Writing to his sister in May 1945, he declared: “I maintain that this war is part of a revolution in men’s minds, and no years of this life have lessened that belief. We are either the fathers of a new hopeful but austere and courageous world or we are the lost generation.” Impatient to get on with the work of reconstruction, he returned to St Ives in March 1946 with an urgent sense of social mission. Once there he painted The Yellow Runner, a dynamic and joyous picture. At its heart lies a subterranean enclosure replete with dormant life about to be roused by the yellow runner sprinting across the hill in the dawn light. These days the painting is associated with a personal narrative of homecoming, marriage and the birth of his first son, but for an audience in 1947, ignorant of the biographical circumstances in which it was made, the work may have been more readily understood in terms of the return of an heroic generation optimistic about the post-war reconstruction.

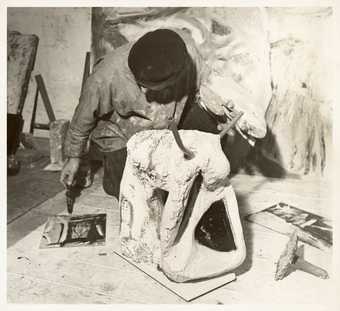

Peter Lanyon

Beast 1953 (destroyed)

Plaster

Black-and-white photograph

Courtesy Sheila Lanyon

The reality of St Ives, a small and fractious community, soon eroded his faith in the ideal he had imagined in Italy. In the ensuing battles over governance and principles of the St Ives Society of Artists and the Penwith Society of Artists, Lanyon began to define himself as a Cornishman among out-of-county “foreigners” and positioned himself as a protector of Cornwall. In the spring of 1950, amid a fierce battle over the Penwith Society of Arts, he published “Face of Penwith” in The Cornish Review, an article indebted to Adrian Stokes’s concept of “outwardness”.

A few months before the publication of “Face of Penwith”, Lanyon, who had known Stokes since the late 1930s, had described himself in a draft letter to the editor of The Cornish Review as “an artist whose debt to Stokes may never be paid” and had quoted the following passage from Stokes’s The Quattro Cento (1932):

“The process of living is an externalisation, a turning outward into definite form of inner ferment. Hence the mirror to living which art is, hence the significance of art and especially as a crown to other and preliminary arts of the truly visual arts in which time is transposed into forms of space as something instant and revealed. Hence the positive significance to man (as opposed to use) of stone and stone building.”

Stokes’s conviction that living necessarily involved the revelation, intended or not, of inner states was informed by his experience of Kleinian psychoanalysis. As a mirror of that process, art acquired considerable social significance, particularly at a moment in history, the 1930s, when many of the ills of the world were, he believed, rooted in the repression of interior life. This was the challenge that he thought faced the modern artist, and which he had seen answered in Britain during the 1930s by Hepworth, Nicholson and Moore.

Although Lanyon did not undergo psychoanalysis, he was receptive to Stokes’s ideas, particularly in terms of what art is and also how one might understand the manmade world. In “Face of Penwith” he applies Stokes’s ideas of authentic revelation and emergence in art to the landscape of West Penwith and the native character of the Cornishman. In it mining, fishing and farming, the industries of Cornwall, are presented as a commerce between the Cornishman and what lies beneath the surface – the tin, the fish and the nutrients. This continuous process of delving down and drawing to the surface is as manifest in the physical structures of those industries (mine works, harbours, fields and farms) strewn over the land as, he argues, in the “centrifugal and centripetal” character of the Cornishman: “A complete trust and desire to give absolutely everything and a converse withdrawal, a returning to a protective native envelope.”

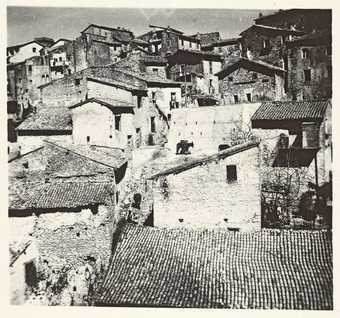

Shortly after the article was published, Lanyon and his wife went to Italy, where they spent a month in the north visiting many of the places mentioned in The Quattro Cento. “One must follow the master,” he said to Patrick Heron of their holiday in relation to Stokes. Whether Lanyon recognised in these sites the process of externalisation Stokes had identified is not known, but he did discover another living manifestation of it in Anticoli in 1953. Situated in the hills 40 miles east of Rome, Anticoli was an ancient village still tied to a bucolic way of life, where farmyard animals and people lived side by side among the steep narrow streets. Lanyon saw Anticoli as a place where the natural cycle of life, death and reproduction, mediated by myth and tradition, was a revealed process: “Here there is dung on the roads and a pig on the doorstep and a great glorious weaving of busts and arses in and out of the piling houses.” The first part of that cycle is memorialised in Primavera, the largest work he made in Anticoli. It was painted as spring came to the mountains and the people of Anticoli and the nearby village of Saracinesco celebrated its arrival with fiestas. Here the painting’s hot bright colours vibrate with an energy consonant with the resurgence of life.

Photograph by Peter Lanyon of Anticoli Corrado 1953

Black-and-white photograph

Courtesy Sheila Lanyon

Peter Lanyon working on a sculpture of a bull in his studio, Little Parc Owles, Cornwall c.1958

Black-and-white photograph

Courtesy Sheila Lanyon

The other phases of the cycle, sex and death, emerged most forcefully in the Europa series of 1954–5, which he considered the culmination of “a long interest in the bull and the woman at Anticoli”, and St Just. One of the reasons Lanyon went to Italy in 1953 was to have a break from the painting that would become St Just. He had started the picture in 1951, and it remained unresolved by the end of 1952. Up until then he referred obliquely to it as a crucifixion, but a photograph probably taken shortly before he left for Italy shows no obvious iconographic reference to that theme. On his return to Cornwall in May 1953, he resumed work on the painting and quickly finished it, adding “the black pole and shaft” that runs down the centre of the picture and forms a ragged crucifix. “I do not pretend,” he wrote, “that St Just is my best statement on the theme of Rome-Cornwall or Lazio-Penwith (a death theme), but it is the outcome of that axis.”

Lanyon visited Italy for the last time in 1957. He arrived in Rome at the end of February and met up with friends, one of whom he had been conducting an affair with since 1955. They visited Lake Nemi and Lake Albano, Anticoli and Saracinesco. Over the next year or so he made pictures related to all these places. In 1961, a year after the affair had ended, he returned to the subject of Saracinesco, and started work on the last and perhaps greatest of his Italian pictures. He wrote of it: “A celebration of a high place and beyond where not only fireworks but moon rockets search for things beyond the primitive proportions of an Italian hill town. The fiesta and the sacrifice are still a part of our behaviour.”

By then Italy was more than the place where as a young man he had seen the possibility of a better world, or had later discovered “a new Cornwall”, or even “the other side of the medal: Cornwall inside out”, it was a fundamental part of his history.