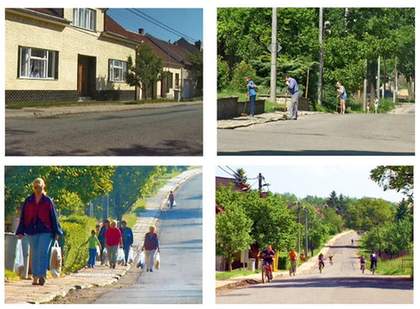

At 10.00 on Saturday 24 May in 2003, all 300 inhabitants of Ponětovice, a small village in the Czech Republic, drew their curtains, switched their lights off and went to bed. This moment marked the end of an extraordinary iteration of an ordinary day there. After some months of persuasion, the villagers had agreed to take part in Katerina Šedá’s There is Nothing There 2003 and had – according to the artist’s timetable posted on the village notice board – shopped at the local store, eaten a meatball and tomato sauce lunch, gone for cycle rides in the park, met for an afternoon beer and returned to their homes, all in unison. Nothing that Šedá asked her participants to do was unusual in itself, but once they were performed en masse, the significance of these chores was heightened by mutual awareness. Everyday activities started to look and feel like rituals. The photographic and film documentation of the piece has the choreographic quality of a slow motion sports event.

Katerina Šedá

There is Nothing There 2003

Shot in Ponetovice, Czech Republic

Film stills

Courtesy Franco Soffiantino Gallery, Turin

© The artist

In New York in the 1960s, the idea of using rules or games as a way of making a kind of choreography known as ‘ordinary dance’ was initiated by artists Yvonne Rainer and Simone Forti, performing at the Judson Theater. In Germany in the same period, Joseph Beuys conceived of society as a whole as one big work of art to which each person could contribute creatively. According to his vision, ‘social sculpture’ was an ephemeral kind of art that could be made from language, thought, action and objects. Šedá’s project – which has also included actions that encouraged meetings between 100 pairs of neighbours in a large anonymous housing estate (For Every Dog a Different Master 2007), and a piece in which the artist asked each household in her village to build steps going over their garden fence so that she could run in an uninterrupted circle through the neighbourhood (Over and Over 2008) – is characteristic of a contemporary approach to art-making that reinvents these mid-twentieth-century ideas for the present. She brings to life what Andrew Hewitt has defined as ‘social choreography’: an aesthetic practice that can actively intervene in the ways that people relate and interact. Choreography or dance, as Hewitt observes, is an artform that is neither simply mimetic nor just decorative, but one that is most intricately woven into the ideology of society itself. Dance, he says, represents forms, and enacts them at the same time. In other words, its doubling up as representation and participation has played a key part in bringing new social patterns into being, rather than merely displaying them.

Performance 2: re-enactment of Simone Forti’s Huddle 1961 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2009

Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2009 Yi-Chun Wu

Katrin Levin

Participants in a Michael Jackson Zombie Flashmob at the Brandenburg Gate, Berlin 2009

© Katrin Levin

Choreography seems to appeal to the current generation of artists as the medium that occupies the thinnest boundary between art and life. It requires no material other than the bodies of its participants, and in this sense it can easily – and powerfully – challenge assumptions about who is performing, who is taking part and who is spectating. Its non-verbal language makes it distinct from cinema or theatre, and it can quickly appear as a form, or disappear. Many artists recognise that even subtle disruptions to norms of behaviour, or elaborations of gesture, can have psychological or mythical as well as aesthetic impact.

Francis Alÿs

When Faith Moves Mountains, documentation of an action near Lima, Peru 2002

Video still

Courtesy David Zwirner Gallery

© Francis Alÿs

Alongside Šedá, there are many examples of this approach to making art out of mass actions that have come to prominence in the past decade. Francis Alÿs’s When Faith Moves Mountains 2002, for instance, created a spectacular choreography as several hundred participants, dressed in matching white shirts, took shovels and – literally – moved the peak of a half-kilometre sand dune in Lima by several feet. For Zhang Huan’s To Raise the Water Level in a Fish Pond 1997, a group of about 40 migrant workers stood still, spread out across the diameter of a large pond, in order to raise its surface level. The LIGNA collective created mass choreographies via the antagonistic insertion of atypical, or even forbidden, kinds of behaviour into surveillance-heavy public spaces – for example, Radio Ballet had several hundred people carrying out instructions transmitted on the radio at Hamburg railway station in 2002. Other notable work in this vein examines the effect that inserting highly controlled or controlling movement into a public space might have. One of the balletic tableaux staged in Pablo Bronstein’s Plaza Minuet pieces (from 2006) was performed in the bland postmodern lobbies of corporate New York, while Tania Bruguera’s Tatlin’s Whisper #5 2008 featured mounted police shepherding crowds of visitors around a space, exerting power but to no apparent end.

Tania Bruguera

Tatlin’s Whisper #5

Performance in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern 2008

Photo: Tate Photography

© Tania Bruguera

The pared-down gestures in many of these recent works might seem, at first, entirely disconnected from early twentieth-century collaborations between art and dance, their interventionist approach a long way from the opulent theatre set and costume designs of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, created by the likes of Picasso, Matisse and de Chirico, or the ‘mechanical ballets’ of Oskar Schlemmer. In those historic projects, the most famous of which was Picasso, Satie and Cocteau’s Parade 1917 – a piece that combined Cubist forms with elements of music hall and circus and an avant-garde jazz and ragtime score featuring sampled sounds (a typewriter, a ship’s siren) – artists and choreographers came together to conjure extraordinary worlds on stage. But that period was vitally important in shaping how we understand the relevance of both art and dance today.

In commissioning artists of his time to design sets and costumes to accompany the experimental choreography of Fokine, Massine, Nijinsky and Nijinska, along with the scores of Stravinsky and Satie, Diaghilev championed the idea that a viewer might not simply look at a painting on a wall in a gallery, but may imaginatively project themselves into the world of that painting, and inhabit it. In classical oil on canvas, this idea of imaginative projection into painted space was much simpler, because the painter deliberately conjured a sense of depth and perspective. Modernist painting, characterised by a concern with flatness and surface, required a radically different way of entering it. In a sense, those theatre pieces argued the case for a new kind of art’s relevance. Dance was the perfect aesthetic complement for many of the artists working in this period: the ideal way to summon an image of modernity, a vision for a new world stripped of nineteenth-century ornament, that fused the colours, forms and lines of their painting practices with similarly stripped-back stylised movements and gestures.

Giorgio de Chirico, who designed 26 performances throughout Europe, including The Jar 1924 and The Puritans 1933, perhaps signifies the transition from an older idea of a painted space into modernism. He transposed the metaphysical space of his paintings into the world of the theatre, stating: ‘Performance must free us from reality and give us a way to immerse ourselves, if not in a different world, at least in a different life.’ Overridingly, though, it was the languages of abstraction that gained the most ground via these collaborations, which returned a role for the human body to a form of image-making that had emptied out figuration. A work such as Les Noces, with choreography by Nijinska and set and costume designs by the Russian painter Natalia Goncharova, represents a key moment. Goncharova’s costumes connoted the simple, austere dress of Russian farm workers, in brown and cream tunics, and – like the choreography, and her own style which blended Futurism and Constructivism – fused ideas of industry and primitivism, mechanism and folk tradition. Likewise, the Belgian dancer Akarova realised her ideas on the kinaesthetic, in relation to the Belgian art movement Plastique Pure, in collaboration with painter (and husband) Marcel-Louis Baugniet, on the stage. Influenced by Constructivism and Suprematism, the set designs they made together for works such as Allegro Barbaro 1929 and La Danse D’Amour 1929 included rhythmic structuring and the use of bold primary colours, contrasting with black and white. Her stage works effected a total synthesis of the concerns of painting and a habitable, theatrical environment to create a ‘living geometry’. Famously, too, the director of the Bauhaus in the 1920s, Oskar Schlemmer, created gesamtkunstwerk, combining sculpture, dance and pattern in astonishing works such as his Triadic Ballet 1922. He sought to stage a language of movement that both reflected the nascent technological age of his time and, at a symbolic level, proposed a total vision of his utopian design for modern living. Evolving from early works such as Slat Dance 1916, in which wooden slats were affixed to a dancer’s limbs and torso as angular extensions of his ‘line’, Schlemmer developed complex pieces in which his dancers performed in extraordinary painted ovoid and hooped armour and stuffed costumes fitted to their bodies, combined with metallic masks and head pieces. They danced mechanically, as ‘living sculptures’ that resembled marionettes.

The Belgian dancer and choreographer Akarova in Allegro Barbaro, wearing a costume of her own design 1929

Courtesy Archives d'Architecture Moderne, Brussels

Despite the avowed aims of this historic work to reflect the speed and energy of urban modernity, it was presented in a manner that was clearly cut off from reality – on the theatre stage. In this sense, the contemporary artworks that I describe are quite different, being applied or inserted into the scenography of everyday life. But it is worthwhile to consider these two moments of activity – the 1920s and the 2000s – as points that are related. They pivot upon the boundary-breaking work of Rainer and Beuys, or Allan Kaprow’s happenings from the 1950s and 1960s: artists who broke the fourth wall of theatre performance to situate their work in a relationship with the world at large. It opens up a way of thinking about how many contemporary artists are still fascinated by the expressive qualities of bodies moving en masse, and why they turn to performance as an ephemeral, and deliberately public, way of making pictures. Where the modernist painters sought to invent worlds that brought their formal innovations to life onstage, proffering the building blocks for revolutionary new visions for modern living, recent art is often embedded, disruptively, in the social fabric itself. Arguably, it is through these kinds of exchange with the world of art that dance is being re-examined, and revitalised as a critical medium. The tendency towards large-scale choreographic actions is only one strand of a broader interest in the area that has given birth of late to a number of exhibitions examining the theme – from Hamburg Kunsthalle’s recent Nijinsky show, to Pierre Bal Blanc’s Living Currency (shown at Tate Modern in 2008), to While Bodies Get Mirrored: An Exhibition about Movement, Formalism and Space at the migrosmuseum in Zurich and Move: Choreographing You at the Hayward Gallery in London, that group contemporary artists on a dance theme. There was also a notable number of artists in this year’s Greater New York show and the Whitney Biennial who have an engagement with choreography: whether the salsa and striptease lessons taken by Ryan McNamara (Make Ryan a Dancer 2010), Kelly Nipper’s reinterpretation of Schlemmer, or Rashaad Newsome’s documentation of men doing the dance known as vogue.

Henri Gissey

Louis XIV as Apollo 1653

Pen, wash and gouache

16.7 x 26 cm

Courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

It might seem surprising that the evolution of choreography from the world of modernist theatre into an applied form injected into everyday life is a progression that runs in the opposite direction from the evolution of ballet itself. The ‘high’ aesthetic form of dance on stage developed from formalised versions of the social dances of its day. One of its earliest recorded choreographic spectacles was the Ballet Comique de la Reine, commissioned by Catherine de Medici in Paris in 1581. Six hours long and on a mythological theme, it was presented not on a stage, but on the floor where members of the court themselves would have danced. Indeed, ladies of the court participated in the performance, rather than professional dancers. And the behaviour developed through dance and ballet came to be accepted as a highly coded form of physical etiquette that informed one’s status. In this sense, the period of the nineteenth-century Romantic ballet, in many ways still the reference point for the medium, is perhaps the most fossilised moment in the history of dance. It’s that moment that we summon when we think that dance is not, or cannot be, a political medium. In fact, dance is fundamental to the cultural identity of most societies. As a combination of ritualised, rhythmic gesture and group and partner interaction, it deals with the very foundations of how we negotiate our relationships by proposing harmonious or disjunctive patterns that have an organic quality; ways of being alone, and being together.

Gillian Wearing

Dancing In Peckham 1994

Film still

Courtesy Maureen Paley, London

© Gillian Wearing

Participant in LIGNA’s Radio Ballet Leipzig at Leipzig station 2003

Photo: Eiko Grimberg © LIGNA

Through the past century, dance has been in and out of the spotlight, but its relevance to contemporary art grows ever stronger: from early twentieth-century mechanical ballets, to social sculpture, to ideas that emerged in the 1990s around ‘relational aesthetics’. Choreography is a tool for making images out of ordinary social relations. In our media-saturated lives now, there is also a fascination, I think, for the idea of dance as a primary activity. Across the range of possible gestures, from picking up a shovel to dig into a sand dune to performing a pirouette, it is a capacity that is latent in anybody. By framing certain activities as forms of dance by considering the roles of attitude and gesture in determining social life, artists rejuvenate its emblematic function and so create possibilities for imagining new kinds of community, or communality. Just as the economical forms of abstraction offered a visual language that rapidly gained ground internationally, performing bodies propose an increasingly powerful contemporary vocabulary. If popular consciousness in early twentieth-century politics and culture – whether the ‘mass ornament’ of Tiller Girl-style entertainment, or military images of fascist sameness – initiated suspiciousness of the mass gesture, the current generation of artists dares to return to this territory with a combination of utopian aspiration and critical awareness. Choreography – literally writing with people – links how one behaves to one’s conception of what a society, or a culture, looks like as a whole, and how one performs a part in that. ‘Everyone is a dancer’ is perhaps what Beuys should have said.