Beatriz Milhazes’s paintings are seductive. They are like a rare Amazonian plant – at once both ravishing and deceptive, full of layers, unexpected tricks and treats. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1961, Milhazes has over the past two decades built up a rich and complex repertoire of images, forms and colours in her work. While she shows an adventurous fusion of influences, her canvases have an undeniably Brazilian flavour – filled with brightly coloured elements relating to a string of popular Brazilian motifs, from carnival-inspired imagery to tropical flora and fauna.

Many of these explosions of colour originate in her small, compact studio, where she has been based since 1987. It is situated right next door to Rio’s luscious botanical gardens, and, inevitably, the forms and patterns of the flowers – delicate swirls and leaf-like shapes – have found their way into her paintings. She has also ‘taken advantage of the atmosphere of the city’, with its rich urban mix incorporating chitão (the cheap, colourful Brazilian fabric), jewellery, embroidery and folk art. Other influences range from architectural – the work of Roberto Burle Marx, the landscape architect and garden designer who created the five-kilometre Copacabana beach promenade in Rio – to Pop symbols such as Emilio Pucci fabric patterns. Painterly inspiration comes from the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Albert Eckhout, who travelled through colonial Brazil, and the Brazilian Modernist Tarsila do Amaral, as well as Mondrian, Matisse and Bridget Riley. Evidence of her terms of reference can be found pinned to the walls of her studio – magazine fragments, postcards and pieces of clothing, as well as some of her own drawings.

Beatriz Milhazes

Avenida Brasil 2003–4

Acrylic on canvas

300 x 400 cm

© Courtesy Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo, and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Milhazes often works on several pictures at once. She begins with an idea of colours and images, but ‘nothing is clear until the end’. While this may suggest a lack of order, each painting seeming to be on the brink of collapse, threatening to engulf the viewer, the artist is in fact ‘very disciplined’ and sticks to a rigid routine. The end products are dense compositions that reveal a precise and delicate hand.

Milhazes emerged around the time of the Brazilian movement Geração Oitenta (the 1980s Generation), which, as in Europe and the US, proclaimed a return to painting after the rather austere art of the 1970s. The new spirit of hedonism, with pleasure as its liberating motto, was largely expressed in vivid brushstrokes and rich colours. During this period Milhazes studied at Rio de Janeiro’s Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage (from 1980 to 1982), the art school located in a beautiful belle époque mansion in one of the city’s parks. Whatever aspects she may share with this group, she also has something in common with the ideas of Oswald de Andrade (1890–1954), the Brazilian poet and novelist. His Manifesto Antropófago, or Cannibalistic Manifesto, published in 1928, was a key text of early Brazilian Modernism. ‘Tupy, or not tupy, that is the question,’ he wrote (Tupy is a language spoken by his country’s natives). It was a profound reflection on the dilemma of the Modernist intellectual caught between high European literary and artistic references and his/her own native sources.

Beatriz Milhazes

Palmolive 2004

Acrylic on canvas

199 x 249.5 cm

© Courtesy Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo, and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Beatriz Milhazes

Panamerican 2004

Acrylic on canvas

198 x 179 cm

© Courtesy Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo, and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

The artistic landscape of Brazil has changed much since then, and Milhazes’s work now has a global audience. In the past year, for example, she has been involved in collaborative projects with other disciplines, including the design of a covered façade for the new Selfridges store in Birmingham. She was recently interviewed by fashion designer Christian Lacroix (currently head of Pucci) – and it is easy to see why. They share a passion for colour, combined with an intuitive yet finely crafted working process.

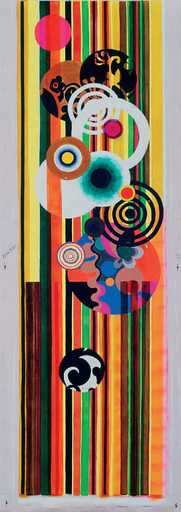

Beatriz Milhazes

O Caipira 2004

Acrylic on canvas

250 x 73.5 cm

© Courtesy Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo, and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Closer to home, at the São Paulo carnival, the Nênê de Vila Matilde samba school featured a whole section of sambistas in Milhazes-inspired costumes. It is clear that her ideas and images have a life far beyond the dimensions of her canvases.