Lynne Cooke

What is particularly interesting about the exhibition Art & the 60s: This Was Tomorrow is that, for the first time, it brings architecture and photography together with the fine arts at Tate Britain. Normally, as you probably know, architecture and photography fall under the aegis of the Victoria and Albert Museum, which was founded to concentrate on the applied arts considered from a pedagogical perspective. Unlike MoMA in New York or the Pompidou in Paris, Tate’s mandate does not include these disciplines.

Rem Koolhaas

Was this a formal arrangement?

Lynne Cooke

I think it was formalised early in the twentieth century. In recent years, however, it has broken down with regard to photography because so many artists today, such as Thomas Struth, practise as photographers. But with architecture, as far as I know, there has been no integration as yet.

Rem Koolhaas

Was that due to the narrowness of the times?

Lynne Cooke

Well, it was also something to do with the status of architecture and photography at that moment. Even in the 1960s, when there was so much talk of crossovers between the various art forms, architects seemed to stand somewhat apart. For example, the openings of the two key galleries of the time – Kasmin and Robert Fraser – were attended by a very diverse crowd that included Marlon Brando, Stanley Kubrick and the Rolling Stones, but as far as I know, no major architects. When you went to study in London in the late 1960s did you have a sense that architects were part of a larger scene?

Patrick Hodgkinson

The Brunswick Centre 1968–72

Rem Koolhaas

Yes, very much so. I think it was a really interesting moment – a time when any communication was questioned, when it was far from self-evident. It’s infinitely more parochial now.

Lynne Cooke

In the sense that there is less engagement with artists from other fields?

Rem Koolhaas

On the surface there is more engagement – you have only to look at the architecture magazines to see it. But in practice there isn’t, and that’s mutual. For example, if you read the art magazine Frieze, particularly in the past five years, you find that it’s really withdrawing into its own territory, art… it’s amazing. The great thing about 1960s architecture in the UK is that it was realised in sites that are so accessible. All these buildings are still around, and in the normal course of things you see many of them, some once a week.

Lynne Cooke

Yes, but you see Richard Seifert’s Centrepoint or any of those other key 1960s buildings in the middle of what is still today essentially a Victorian or Edwardian city. For all the discussion of a radically changing streetscape, of the re-urbanisation of London, these Modernist buildings seem like nodes inserted into something that wasn’t fundamentally changed.

Rem Koolhaas

That is an interesting point. In Europe, change is either resisted or wholesale – in London, you wonder whether cumulative change is not a very smart way of changing? Maybe the latter makes a little more sense. I’ve always felt that because the British don’t have strong theoretical ambitions – because they are sentimental – they have an interesting inability to implement things on a theoretical level. If you look at Denys Lasdun’s Keeling House, it’s sensational precisely for that reason. Never claiming that the whole context should be erased, the British actually got away with this kind of intervention. Meanwhile, everyone else in Europe was trying to erase everything and so never got to the point of creating this eloquent interface between old and new.

Lynne Cooke

But how good do you think most of the buildings were? Was compromise inevitable with this kind of intervention?

Rem Koolhaas

Ironically, because so much of it was built for the public good, we now tend to think that it was compromised – simply because it was not ‘unique’ and had no signature. What was generated in a spirit of benevolence looks impoverished to us, because we need the iconic to begin to pay attention.

Lynne Cooke

And we’re now talking of Patrick Hodgkinson’s Brunswick Centre housing project, which was not the worst by any means.

Rem Koolhaas

No. We can, of course, raise the issue of quality, but at the same time we can only regret the way our own expectations have become inflated, burdened with aesthetic and material demands that those people quite heroically decided to forego. In some ways we are very spoiled. If you look at Neave Brown’s Alexandra Road Estate, you can see that we now demand luxuries, such as certain textures, that they were confident enough to have purged.

Lynne Cooke

Does this imply that the aesthetic aspect is something of an overlay that can be added or subtracted; that it isn’t integral from the beginning?

Rem Koolhaas

Basically, there used to be an absolutely immediate and direct connection between architecture and an ideology of equality. Today, we find this hard to take, aesthetically. In a way that was largely unconscious we abandoned that connection: even if our heart is in the right place, we are excited by the exceptional and enjoy masterpieces. For me this situation raises a question not only here in England, but when I go from West Berlin to East Berlin, or when I travel to Moscow: the levels of luxury and surfeit in which we indulge now become very apparent in those zones of former equality.

Cedric Price

Cover design for Generator, to accompany his exhibition at the Waddington Gallery, 1981

© Hillingdon Press (Westminster Press)

Lynne Cooke

Is that a product of the type of architecture that dominated the 1990s – buildings that were generated by the private as opposed to the public sector?

Rem Koolhaas

They were connected to profit: they changed the city, yet they were not connected to urban change.

Lynne Cooke

Do you mean they were isolated – autonomous – rather than integrated?

Rem Koolhaas

Yes. A self-evident consequence of the profit motive is the fact that most of the changes to the city were not made according to any established programme or ambition. Many of the buildings of the 1960s are really clumsy and awkward, but even if they have few aesthetic virtues or qualities, they do have a sense of being deliberate, of being part of a plan or blueprint.

Lynne Cooke

As with Manchester’s Piccadilly Plaza or the Bull Ring in Birmingham, many UK cities had their centres – their hearts – redesigned. Are they identifiable or distinguishable from each other? Do you think that was important?

Rem Koolhaas

The beauty of, for example, Covell & Matthews’s Piccadilly Plaza is that people were so convinced, so secure in their sense of what London or Manchester was that they could even see the programmatic aspects [of the design] – their deliberate neutrality – as a contribution to their status. I’m always really astonished at the simplicity of what architects could get away with then. By contrast, it’s almost obscene what we’re forced to produce now. Ironically, ‘identity’ has become one of those obligations. We are in a very invidious moment in the sense that although we may not explicitly condone capitalist virtues, we contribute to the cult of identity, often at the expense of the authenticity that easily coexisted with the more naïve architecture of our immediate predecessors.

Lynne Cooke

Does that mean public housing projects are no longer possible?

Rem Koolhaas

They’re no longer possible, or at least nobody does them.

Lynne Cooke

You’ve spoken a lot about Cedric Price and how important he was. You have also argued that ideologues or theorists haven’t really played a very strong role in Britain. Since he built almost nothing, how do you reconcile this apparent contradiction?

Rem Koolhaas

I think Cedric Price did unbelievable things. He was an ideologue but not a theorist. In general, I am very sceptical that you can be theoretical in architecture, because there is really no theory. There are precedents, directions and movements which generate forms: it’s very important to separate that from theory. The most interesting part of Price for me is that while he was, in a certain way, an arch nostalgic and conservative, ultimately, his most radical and innovative contribution was his relentless and endless questioning of the claims and pretensions of architecture and architects. He was a sceptic torturing a conservative discipline. So, the 1960s are very compelling in two ways. On the one hand there’s the scale and the sincerity and earnestness of the effort, and, on the other, the ruthlessness of the questioning of that very effort by people such as Price. Presumably, there is an internal connection between the two: he could only be ruthless because the period produced strong and compelling forms.

Lynne Cooke

Yet there are curious anomalies in this situation. For example, not only the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner but also Peter and Alison Smithson tried to preserve the eighteenth-century streetscapes of Bath and the Euston Arch in London. That is, both the conservative and the more vanguard positions encompassed a strong sense of history and accorded it a role or place in the present, even while they did not share a belief in what should be built in relation to what remained of the past. Almost nobody advocated a tabula rasa – the idea of starting again with a clean slate – as the way forward.

Rem Koolhaas

The whole issue of the tabula rasa is really interesting. I believe that a sense of history is ingrained in architecture probably more solidly than in any other profession. For instance, the average architecture student knows more of history than the average painter does. Our fundamental genetic material is so ancient. I am not surprised – and I wouldn’t call it a form of conservatism either – that such elements as the Euston Arch would be an issue for preservation. I can’t imagine a single architect at that moment proposing to get rid of it – except, maybe, in the interests of commercial development. The myth of the tabula rasa has had a very interesting life in architecture. It was proposed in the 1920s more as a poetic than as a literal notion. Then in the post-war world it flipped over, becoming the most serious crime that an architect could ever commit. It was at first a form of propaganda used by architects to make their case more vividly and, presumably, also to advance their careers, but then it became the propaganda of the non-architects against architects.

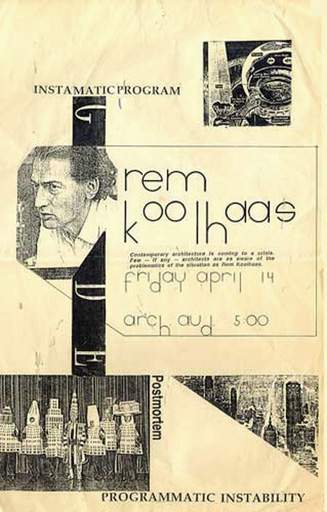

Flyer for the Koolhaas talk ‘Programmatic Instability’, 14 April 1989 at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s College of Architecture

© Andrew Seward Duncan Collection

Lynne Cooke

The most extreme case would be Le Corbusier.

Rem Koolhaas

I never believed that there was a serious effort to be anti-historical, even with iconoclasts such as Le Corbusier – it is mostly a myth that has turned against architecture as an inescapable form of original sin.

Lynne Cooke

You mean he didn’t intend to execute his programme; he didn’t intend to raze a large part of Paris?

Rem Koolhaas

No. I’m sure that he chose the most beautiful part of Paris simply to make his point. You should also not forget that after the Second World War there were actually many tabula rasa situations that existed for other reasons, independent from architecture. I think somebody should write a really serious history of the tabula rasa; I’m sure you would discover some incredible discrepancies compared with the official story. For example, I’m totally convinced that a project such as Peter and Alison Smithson’s one for Robin Hood Gardens was in every sense conceptualised to coexist with all its then neighbours and the norms of that kind of context.

Lynne Cooke

In different ways Richard Hamilton and Peter Reyner Banham, who seem to me to be the other key figures of this era, embrace these poles, forging a new alliance between the overtly modern and the historic. Banham’s seminal book Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (1960) basically rewrites the history of early twentieth-century architecture to accord futurism a formative role. At the same time, he was writing paeans to innovative automobile design and new industrial objects. He’s very typical of a key strand in British culture of the 1960s.

Rem Koolhaas

I think the so-called purism which architects are often accused of is a projection, almost a hope – the rest of the world hopes that we, at least, have remained pure. Architecture is a strange trope because it is so associated with elimination, with purism and intolerance, that both within its own domain and outside any sort of ambiguity is immediately considered an inconsistency. To the outside world the consistency of architecture is a given, from which you deviate at your own peril – which is ironic since it would be much better, and much more interesting, for the world at large if there were more deviations.

Lynne Cooke

By the 1960s there was a big contrast between Britain and the United States, where the notion of the tabula rasa was polemically invoked by artists ranging from Barnett Newman to Tony Smith and Donald Judd, variations on a well-rehearsed desire to leave the past behind. When you were writing Delirious New York in New York in the early 1970s, did you feel you were writing from within a milieu in which this was still a current notion?

Rem Koolhaas

This may seem a subtle difference, but it’s not unimportant. Although 1972 seems, in several fundamental ways, part of the 1960s, I would say that Delirious New York was written more as a polemic against the first signs of Post-modernism in architecture, rather than as an argument against modernity. This is definitely a book about Europe and America – it was dissatisfaction with the mentality in Europe that drove me to write it – but, at the same time, I was using a former America against the Post-modern America. So in that sense it had a double agenda. My ambition with Delirious New York was to identify and put on the map another Modernism. We Europeans are reasonably conversant with the ideas of Suprematism, Dadaism and Surrealism, but we know little about the world of experimentation that occurred in parallel in the United States: America’s inter-war Modernism. It seemed important to identify that particular form of Modernism, because in the US historicism and post-modernity were being glorified. If you look at the 1970s, there were moments when our office and a few others really seemed deeply isolated in maintaining any interest in the issue of modernity.

Lynne Cooke

Why did you leave Britain for the United States? Were you dissatisfied with what was happening in architecture in the UK?

Rem Koolhaas

Now, when I look back with you at pictures of 1960s Britain, I can respond more positively to the puritanism than I could when I was a student. Then the puritanical aspect of architecture upset me. The reason I left Europe was a frustration with the limitations imposed on architecture, with the limited way in which the growing interest in the historical city launched by people such as Aldo Rossi was used to discredit architecture.

Lynne Cooke

You left Britain in 1972. Later Banham left, along with a lot of other people who had been looking closely at the States during the 1960s. Cedric Price didn’t, and he built almost nothing. Do you think his contribution would have been different if he had worked in the US, or did he depend on this state of confrontation?

Rem Koolhaas

That’s a really interesting question. He did participate in competitions abroad, for example for La Villette in Paris. If my memory is correct, I think he also proposed projects for an estate somewhere in Florida. He journeyed regularly to America and also to countries that considered themselves as outposts of the London discourses. It is fascinating that he is making such an incredible comeback. I’m not sure anyone really knows why. Maybe in some way he represents our guilty conscience.

Lynne Cooke

And unexplored directions?

Rem Koolhaas

Yes. If I look at the new library in Seattle, maybe in a pathetic way we are trying to be Cedric Price The folding and the facets of this building are actually quite close – in terms of their diagrammatic machine-like quality – to Price’s aviary for London Zoo. There are many features of that moment.

Lynne Cooke

I wonder if you could trace another lineage that went from the idea of Price’s Fun Palace – as a kind of non-hierarchical cultural goods yard where people would constantly re-position elements in order to have different art forms come into play – and the Pompidou as it was originally conceived, or your project for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Rem Koolhaas

I don’t know a single person who doesn’t believe that the Pompidou was derived from or intimately connected with the Fun Palace in some way. But LACMA is not a free-for-all, nor even a non-hierarchical situation. It is more an attempt to deal with the encyclopedic museum in general. Whereas the Pompidou is basically a loft-building on several levels, with the LACMA proposal I attempted to exploit what is theoretically the greatest potential for an encyclopedic museum – that it enables the display of parallel developments, across time. It offers an overview of several time-lines running in parallel. In an historical museum, periods and categories are “put in their place”. They have their own section, wing or pavilion. The essence of LACMA is that it was set on a single plate, presented as an historical grid in which every kind of thing could be positioned so that you could see cultures develop in time, and make cross-references between them. You can never do that in a building with different levels or sections.

Lynne Cooke

But its whole is contained within a neutral frame?

Rem Koolhaas

But I think the form was not neutral. In the first proposal it was perhaps more neutral. We were to present it on 12 September 2001. After 11 September, the presentation was postponed and in the interval we modified it drastically.

Lynne Cooke

What were the paradigms that moved it away from neutrality?

Rem Koolhaas

Somehow, after 11 September neutrality felt too cold. It was nothing more concrete than that, but it helped us to move to a proposal that was less clinical. If you ask for reasons in architecture, it is always delicate, because things have to be presented as reasons or as reasonings, even if they are simply intuitive leaps or adjustments to contingencies.

Lynne Cooke

Do you think the Fun Palace idea is not viable at this moment?

Rem Koolhaas

I think that could be true. Maybe Tate shows the extent to which it is no longer possible, because the empty space at Tate Modern could be seen as the Fun Palace and it would be very exciting if it worked, but it has become a severely programmed museum space. There’s none of the blurring of those earlier times: we demand clarity and consistency from our artists today, so maybe that prohibits a leaking from one area to another. Although there is more multi-disciplinary activity now, it seems too programmed to lead to the sort of discoveries that were made then.

Front cover of Reyner Banham’s Theory and Design in the First Machine Age

© The Architectural Press, London, 1960

Lynne Cooke

The other idea of Cedric Price’s I wanted to ask you about is his notion of magnets as distinct from iconic statements – buildings which are integrated in a context, which imply a certain degree of cohesion rather than standing out as signature statements?

Rem Koolhaas

You have to consider that Price was lucky in a certain way: most of his work and most of his statements were made before the whole idea of a signature even emerged. It’s the most corrosive idea. At this moment it creates an incredible pressure because it is inescapable. There’s no way to outwit it. But maybe you can ignore it, with more or less effort. So while I sympathise with his notion on a fundamental level, in our culture it’s almost untenable, because so much has to ‘pay off’ somehow – literally.

Lynne Cooke

There is an implicit claim in the Art & the 60s show that both the 1960s and the 1990s were extraordinary moments in British culture.

Rem Koolhaas

The 1990s were exciting mostly because of the internationalism of the country, but they didn’t have any internal relationship with the 1960s. The special thing about the 1960s in the UK was that people were able to be simultaneously parochial, creative and innovative – and usually those three don’t go together. They were geniuses in cultivating that. There were totally bizarre fairytales, very myopic and intensely idiosyncratic engagements with certain contextual moments but still generating a surprisingly wide field of discovery. So I think the main difference between the 1960s and the 1990s was that the 1960s constituted maybe the last parochial moment, but one that was used almost as a tool. When I came to the Architectural Association in 1968, there was a dining room with waitresses and a fireplace. It was an incredible scene, because the most moribund elements of English culture were being used as props against which the avant-garde could perform its tricks. There was a mutual reassurance and interdependency for the avant-garde to know that there was this background, and for the background to know that it was the last spasm of a particular culture that couldn’t last. There was a great pleasure in it, I think. That kind of role-playing is almost absent now because, basically, you can no longer have the luxury of the foreground and background: everything has become the foreground.

Lynne Cooke

Yes, the Courtauld Institute, which was then located in a Robert Adam house, was like that too. The teaching faculty walked down the grand ceremonial staircase, while the students had to use the back staircase – the one designed for the servants. Yet everyone ate together in the small, tacky café which was valiantly run by a single woman. While full of contradictions, the Courtauld was actually very productive.

Rem Koolhaas

You can probably trace the flattening of a certain culture with the modernisation of bars and of interiors – with Minimalism raising its head everywhere. Taste.

Lynne Cooke

This brings us back to the idea you stated earlier: that today we require ever more luxurious settings. This completely undermines the makeshift.

Rem Koolhaas

Makeshift is a beautiful word. It connected with Banham and Price, but we cannot handle it any more.