Cedar Lewisohn

Peter Ustinov said comedy is simply a funny way of being serious, but what exactly is satire and how has it changed over the centuries?

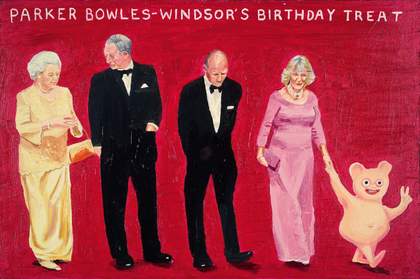

Brian Griffiths

Satire is a very particular type of humour. It is a form of intellectual wit is it not?

Paul Gravett

Humour might be there, but some satire can be pretty bleak. It’s intended to be an attacking weapon. I think Viz is one of the best examples of current satire. You are looking at what’s happening in culture right now, and skewering it.

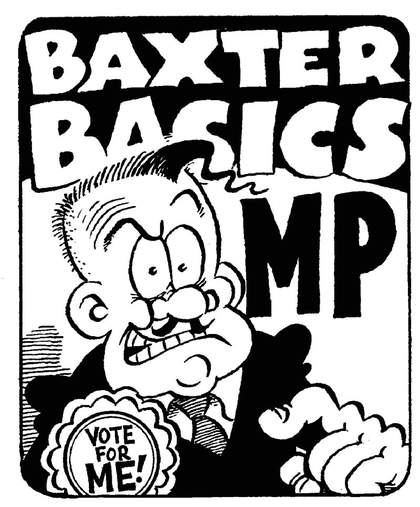

Drawing by Simon Thorp, co-editor of Viz, of Viz character Baxter Basics (1993)

© Viz

Simon Thorp

But that’s what any sort of comedy does. As far as Viz is concerned, I tend to think we don’t really skewer people so much as hit them with a sledgehammer. It is brutal and coarse. We’re not very focused, we just sort of lash out in all directions.

Paul Gravett

In theory, yes, but some comedy can be much milder. It isn’t always so honed in on a particular topic or target in the way that traditional satire is.

Brian Griffiths

There’s also a great tradition of satire that comes from literature, such as Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels or A Modest Proposal. In the case of James Gillray, his target was quite wide, from royalty to aristocrats to celebrities of that period. Or even down to the affectation of fashion.

Paul Gravett

It’s true some satire comes from literary tradition, but there are many other aspects to it – for example, caricature has a long history. It was described as an aristocrat’s hobby, which is one thing that Hogarth was so against. It’s taken on a particular power when it’s been used for political purposes, as it was with Gillray. We know caricature can be really effective. I certainly can’t think of Margaret Thatcher or John Major without thinking of Steve Bell’s portrayals of them.

Simon Thorp

Or the Fat Slags in Viz, for example. They are a sort of shorthand.

Brian Griffiths

In terms of satire, what I find interesting is what it actually does. How effective is it?

Gerald Scarfe

Cartoon Smith for Sale of Ian Smith, Prime Minister of Rhodesia, published in the Sunday Times, 8 December 1974

Courtesy the artist © Gerald Scarfe

Cedar Lewisohn

If you think of the satirising of Sarah Palin in the last American election, that certainly had an effect on her public image.

Simon Thorp

I wonder if a reasonably restrained way of caricaturing people is more effective than the blood-dripping fangs variety. When I was at university I went to see some Gerald Scarfe drawings of Ian Smith [the then Prime Minister of Rhodesia], who seemed like a proper target. But if you draw somebody less malevolent using the same sort of language of monstrousness, your vocabulary is being used up and there’s nothing left.

Brian Griffiths

From an artist’s perspective, what I find really curious is the fundamental question of why we use humour as a way of attack. In part, I think it’s because humour has social reach: it’s something we all have in common and is what makes us different from other animals. We can laugh at power, politicians, institutions – at everyone.

Paul Gravett

I don’t know how effective it really is. We can laugh at our leaders, but that doesn’t stop them being our leaders, and we don’t do anything more than get our chuckle from Steve Bell every day. In fact, I feel there’s a kind of collusion, certainly since maybe the 1940s and 1950s, whereby politicians actually want to be caricatured because it’s a sign they’ve arrived on the news stage. They collect their cartoons; they are the biggest market for them. At the same time, you might argue there’s an increased anxiety today, with the whole Danish Muhammad cartoon fury and the Obama New Yorker cover storm. There’s a whole offenserati that’s primed and ready to be offended, so suddenly cartoons have become dangerous.

John Cleese in Monty Python's Ministry of Silly Walks sketch (1970)

Courtesy Python Films

Cedar Lewisohn

You don’t sit at your desk drawing, surely Simon, thinking: I’m going to overthrow the government with this next one?

Simon Thorp

No, drawing people with piles or having sex with gingerbread dolls would be a very feeble way of overthrowing the government.

Cedar Lewisohn

Do you actually go directly for any political satire in the traditional sense?

Simon Thorp

Not really, not party political. We have a cartoon character that’s an MP, but he’s been in both parties. He started off as a Conservative in John Major’s day. He was called Baxter Basics. He was sort of a Victorian values, sleazy Conservative. Then he moved over to New Labour during the 1997 elections. When Major was about to lose, we moved him to the winning party. I actually think he’s probably more of a Conservative these days. We’ve probably forgotten what party he’s for now, he’s just generally a politician.

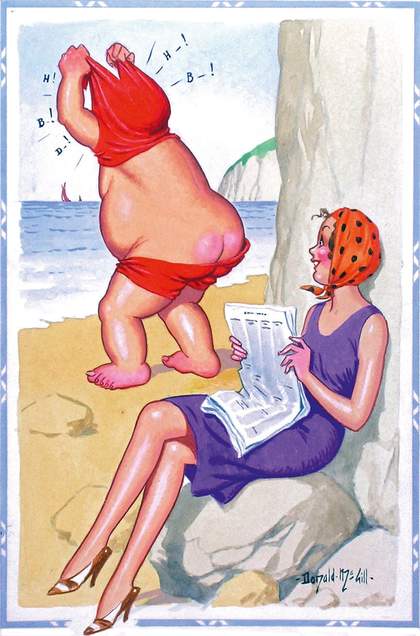

Donald McGill There's no news in the paper so I'm looking at the comic strip! undated

Watercolour on paper

22.2 x 16.5 cm

Courtesy Chris Beetles Gallery, London.

Michael Winner Collection

Cedar Lewisohn

Maybe people’s expectations are too high. Why should caricature or art generally, have a political effect? Is that its job?

Brian Griffiths

I think this kind of healthy disrespect is important within a democracy. There’s also an argument that to see an image of Margaret Thatcher repeatedly, on some level reaffirms her power or authority, even if it is an attempt to deflate that power.

Cedar Lewisohn

The effectiveness of humour is not just about the political, but about how it works within social groups or for the individual. It can be liberating. It’s a way of taking up a critical position. It’s a way of distancing yourself. In a TV sitcom such as Porridge, you see how the humour is used by the main characters to keep themselves above water. It’s a kind of comic relief.

Paul Gravett

So much of humour is about turning received ideas upside down. Of course a lot of comic art, and certainly Viz as well, is not trying to do anything other than just be fantastically surreal and nutty. It’s designed to make you see the world in a different, topsy-turvy way. Satire, and comic art generally, often takes something and twists it around. For example, Hogarth based some of his prints, especially the famous A Rake’s Progress and A Harlot’s Progress, on an earlier craze for edifying moral prints from Venice that were cheap and cheerful and very popular. Hogarth was deliberately playing with that low-brow mass medium by making these grandiose paintings and prints. So you had that extra level of knowledge of what he was satirising. You get so much more out of Viz if you know it’s come out of The Beano and The Dandy. It’s based on subverting and playing around with pre-existing forms.

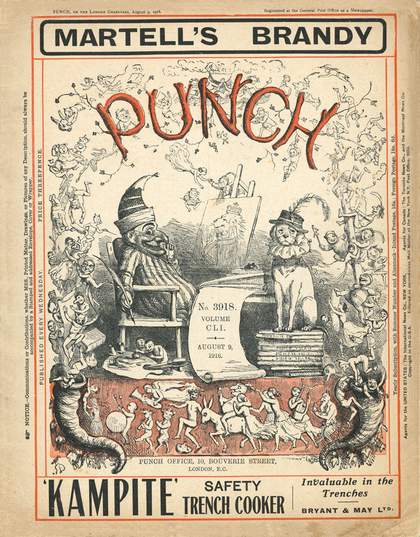

Punch magazine, 12 April 1912

Front cover

Courtesy The Punch Library, London

Private Eye, 26 August 1994

Front cover

Reproduced by kind permission of Private Eye magazine

Brian Griffiths

Often, maybe unsurprisingly, I don’t find early satire funny – because I don’t understand the context. If you do understand the social ticks and conventions, then you can play with the incongruity of it. You have to be an historian or have an investment within that particular form to get the joke fully. It will be the same for something such as The Mighty Boosh in 300 years time, where the idea of the location, Shoreditch, the idea of haircuts, the idea of music, even the idea of the double act, will possibly be lost. So this notion of the universality of humour isn’t necessarily true – time comes into play.

Cedar Lewisohn

How about fart jokes? There’s a long tradition of them. Why do you think this is?

Paul Gravett

The comic artist Eddie Campbell said: ‘The foundation of all humour is that just as we all have a head, so do we also have an arse.’ That’s the point. The Queen, the Pope, anyone will shit in the woods. You can imagine the very first joke was probably some caveman laughing at somebody’s bottom.

Brian Griffiths

Yes. What’s important about scatalogical humour is the fact that it says we are animals. We like to overlook it, but through farting, pissing, shitting, vomiting, we get reminded. Being human is quite a lonely position. We’re not like other animals. We have a reflective attitude, in that we can have a distance from our own experience in the world, and ourselves. So scatalogical humour reminds us of the gap between nature and culture – it rubs our face in it.

Cedar Lewisohn

There’s a lot of caricature and comics which deal with this type of humour: Monty Python films, Bottom, The Young Ones, Derek and Clive, even The League of Gentlemen. Is the tradition as strong in galleries?

Brian Griffiths

There is a strong tradition in art, which uses the scatological often for comedic purposes. This is most clearly evident in performance or video art. It is present in British artists’ work such as Paul Noble’s drawings, or the Chapmans’ diverse practice, or Beagles and Ramsay’s installations. The scatological humour in contemporary art nudges into the profane, the anti-establishment posturing and the juvenile.

Cedar Lewisohn

What do you think, Simon, about your magazine, and comic books generally, in relationship to scatological humour? Is it a particularly British hang-up?

Simon Thorp

I don’t know whether it’s a British thing. The humour comes out of stuff you’re not supposed to talk about. It’s not really scatological. Donald McGill had drawn 8,000 of these saucy postcards without realising, he claimed, there was a double meaning on each one. In a Carry On film or a Don McGill postcard you’d always have two meanings; we’ve done away with the second meaning and just gone for the first one.

Cedar Lewisohn

Do you think there’s something about high-brow culture being so cerebral that it doesn’t seem to want to accept this low-brow material?

Paul Gravett

Duchamp’s urinal is obviously the ultimate joke of bringing toilet humour into the gallery to subvert art.

Brian Griffiths

Many artists or particular movements have explored or used humour, or have been incredibly funny – from Hieronymus Bosch to John Baldessari and Dada to Fluxus. I think humour is there in art, but it isn’t necessarily designed to produce great belly laughter. It’s like Samuel Beckett’s idea of the ‘mirthless laugh’, the laugh that laughs at that which is unhappy. Art is often a re-staging of humour, or uses the mechanics of humour. But firstly, it’s art. You don’t go into a gallery and look for a joke. It’s not your expectation. You may find things funny; I have found things hilarious in galleries, sometimes unintentionally.

Cedar Lewisohn

Do you think there is any kind of crossover between sitcoms, TV sketch shows such as Ali G and Bo’ Selecta and cartoons and comics? Bo’ Selecta probably couldn’t have happened without that ruthless caricaturing in things such as Viz.

Paul Gravett

Certainly someone like Harvey Kurtzman, the creator of Mad in 1952, was a crucial figure. He was one of the first people to parody the whole American dream in a way that nobody had done. He is the father of that modern tradition of satire, from Lenny Bruce to Robert Crumb. You wouldn’t have had the all-important American underground comic scene, and for that matter Private Eye, without Kurtzman’s Mad. Of course Mad didn’t come from nothing. There’s been a long tradition of satirical magazines, going right back to Punch and even earlier, but he did take a very modern approach to it. He questioned the received messages of the media. That was important, because people had gone through the Second World War when you weren’t meant to challenge what you were being told – the cartoons during the war were all anti-Hitler, anti-Nazi. So you needed Kurtzman’s questioning, because the 1950s became a very conformist era.

Brian Griffiths

You could say the Carry On films were like that. They were about social cohesion post-war. They were incredibly conservative. It’s revealing to look at when the Carry On films started in the late 1950s, and when they declined in the late 1970s, as it shows something clearly, not knowingly or intended at the time, about the complex social landscape. The humour is all based on visual slapstick, double entendres and bawdy slapstick. It’s about not saying something directly or explicitly. The whole series of films is concerned with repression. I’m sure Freud, if he were around, would have had a field day with them.

Paul Gravett

How much do you think Viz actually does question and subvert the status quo? Or how much of it, rather like the Carry On films, is not telling you to do anything… not really extolling rebellion, outrage or anarchy?

Simon Thorp

Yeah, I wonder. When you have authority figures in Carry On films, they tend to be portrayed as being as foolish and ridiculous as everybody else. Does Sid James as Henry VIII imply that the royal family is particularly special? They are a little bit subversive in that way, aren’t they?

Paul Gravett

I suppose what you’re saying is more to do with the underlying values of conforming – marriage, family values and so on…

Brian Griffiths

They did reflect society at the time. Some were critical of bad policy or outmoded institutions. Carry On Nurse was a consumer critique on the Health Service. So there is some interesting critical questioning too. But even though it is hilarious at times, it is a humour based on stereotypes and maintaining the status quo.

Cedar Lewisohn

How important is class in all this? The Carry On films tend to be very class orientated. And if you look at some of the historic caricatures that we’re talking about, they seem to be more for the upper class than a populist audience.

Paul Gravett

Punch was an aspirational magazine. It was for your drawing room, and even if you didn’t have a drawing room, you could pretend you had one when you were reading it. Originally, the historic satirical prints by Gillray and company were relatively affordable, and they could also be seen for free on display in print shop windows or coffee houses, or you could hire them like a video, take them home with you for an evening and entertain your friends. They were not intended to be exclusively for the upper classes. But over the years, as they became more prized, they have appealed more to upper-class collectors, politicians and the like, those who get all their historical references which have been largely lost on younger generations.

Cedar Lewisohn

Do you think you’re harder on any particular class in Viz?

Simon Thorp

Well, now that you mention it, yeah, possibly. But we’ve done jokes about everyone.

Cedar Lewisohn

The perfect example on TV of a kind of mini-universe which encompasses a lot of these class aspiration and wider political issues of the time would be Rising Damp.

Brian Griffiths

I grew up in the 1970s and there were a lot of fantastic sitcoms, including Rising Damp. You notice that in particular sitcoms such as Rising Damp, Porridge, Steptoe and Son, and in contemporary sitcoms – I’m Alan Partridge, The Office – there is a certain self-deprecating humour, combined with a palpable kind of melancholy and desperation. It is about a revolt against the claustrophobia of the everyday, the daily routine. That’s what I consider and at times attempt to fold into my art practice. This idea of taking something we know and trying to use that to make an escape to another place. There is also a lot about the aspirations of characters such as Leonard Rossiter’s Rigsby in Rising Damp or Ricky Gervais’s David Brent in The Office, who have dreams beyond their capabilities. I find this fascinating: the fallible, the failure, and how the viewer is positioned to recognise this in their constant anxiety. But also I find compelling the sense of isolation described by these characters. This type of lonely melancholic state runs through a lot of British culture, from Philip Larkin to The Smiths. I think that kind of sadness, the pathos in this context, is tragically funny. It forefronts us seeing our own ridiculousness, our own absurdity in the world.

Cedar Lewisohn

I sense there are those who have this idea about artists generally that they’re having a laugh and getting one over on the gallery, or the system. So there’s an interesting relationship there between how things are perceived by the artist, the maker, and how they’re received by the audience.

Paul Gravett

So was Carl Andre utterly unaware when he made ‘The Bricks’ [real title Equivalent VIII 1966] that it could be perceived as funny?

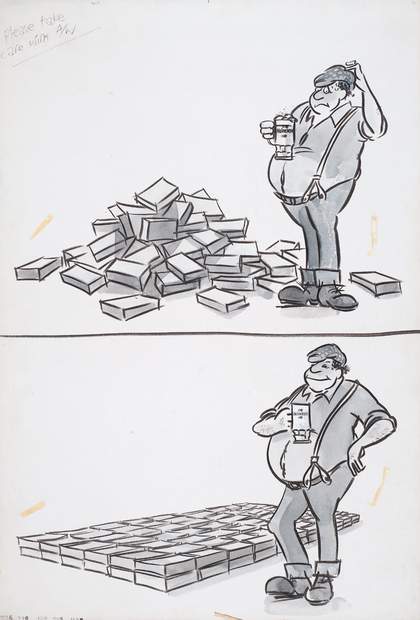

Original drawing for a beer advertisement (1976) inspired by Carl Andre’s Equivalent III in Tate collection

Tate Archive

Brian Griffiths

I imagine Carl Andre had quite serious intentions with the piece..

Paul Gravett

What about someone such as Claes Oldenburg, who made those giant soft sculptures of cream buns, plugs and so on?

Brian Griffiths

Those are probably meant to be funny. What I believe is important, though, is that the viewer may think that Andre’s ‘Bricks’ are funny – there is no wrong response; artists cannot fully control the interpretation of a work once it is out in the world. This comes back to how they often use humour, or how art becomes funny. Many artists are well aware of and investigate the gap between intention and interpretation. David Shrigley, for example, cleverly acknowledges and uses the fact that language is unspecific and often slippery. Language doesn’t always communicate effectively and humour often occurs through this.

David Shrigley

Leisure Centre 1992

C-type print 25.3 x 25.3 cm

Courtesy the artist © David Shrigley

Cedar Lewisohn

In terms of what a gallery is prepared to show, do you think there will always be a contradiction when institutions try to comment on humour, if so much of the content is out of bounds?

Paul Gravett

Well, would Tate have considered showing cartoons that have already caused offence? We know that cartoonists have always been clamped down upon, suppressed, even assassinated. There has been that long tradition of censorship or control, and we’re now in an era where it seems more prevalent. Some of the historical works by Gillray or Thomas Rowlandson would not have been perceived as acceptable in their time and still have the power to shock today.

Brian Griffiths

It’s a really interesting question – how do you shock now anyway?

Paul Gravett

When I was growing up, Viz was really shocking. It was like a top-shelf magazine. Now it’s not, because taste and culture have caught up with it. That kind of humour is standard, and things have moved on. Maybe someone needs to come along and do a satire of Viz. Someone’s going to do it – a spotty seventeen year-old who will print 100 copies.

Simon Thorp

I’ll pursue them through the High Court…