Shizuka Yokomizo

Untitled (from the series Stranger)1998–2000

C-type prints

127 x 108 cm

Courtesy the artist © Shizuka Yokomizo

Sophie Howarth on the increasing risks of taking photographs in public

‘Stare. It’s the way to educate your eye. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop,’ Walker Evans advised his fellow photographers in the early 1970s. How times have changed. Today, tightening privacy laws and international fears about terrorism have combined to create an environment in which to follow Evans’s advice is brazenly to invite suspicion. Although Google Street View casts its omnipotent eye on more and more of our comings and goings, old-fashioned street photography seems an increasingly risky profession. It has become much more common for photographers to be informally reprimanded or officially stopped and searched. A campaign run by London’s Metropolitan Police in 2008 summed up the change in attitude: ‘Thousands of people take photos every day. What if one of them seems odd?’ it read, inviting the public to report anyone with a camera that seemed to display unusual levels of curiosity.

On 23 January this year, hundreds of photographers gathered in Trafalgar Square to protest against escalating restrictions on their freedom to take pictures in public. They mobilised under banners that read: ‘I’m a Photographer, Not a Terrorist!’ Supporters of the campaign included one of Britain’s best-known photographers, Martin Parr, who has said he would never do any work if he had to use model releases every time he wanted to take a picture in public.

American photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia only narrowly escaped a hefty fine when he bypassed model releases for his series of candid portraits Heads 2001–3. He set up his tripod along city pavements across the US and Europe, rigged up a complex flash mechanism using lamp posts and street signs and then simply waited for the passers-by to come along and trigger the illumination device. His subjects were unaware they were being photographed, but when one of them, Ermo Nussenzweig, discovered his portrait had been exhibited on the walls of a commercial gallery and published in a book, he took diCorcia to court. He argued that his privacy and religious rights (he is an Orthodox Jew) had been violated by both the taking and publishing of the image. The extensive legal battle that ensued went to the highest state court in New York, where the judge ruled in the photographer’s favour. Street photography is art not commerce, he pronounced, and therefore falls under the First Amendment, which safeguards freedom of expression.

However, photographers do not exist in a moral bubble, and those who have assumed that an unfettered right to point a camera at a stranger somehow flows from the Magna Carta or the Bill of Rights do not help the delicate contemporary situation. It may be understandable to a certain sensibility that freedoms for photographers should be derived from more general public liberties, but the truth is that photography has always had to negotiate its place alongside complex social mores. Such was the concern in Victorian England, for instance, that women’s modesty could be at risk from a surreptitious lens that photographers required official permits to shoot in parks. Today, photographing children without parental consent is widely considered unacceptable in the West.

The photographs in ‘Exposed’ remind us just how tortured the relationship between photography and privacy has always been. The beautiful, the damned, the blind and even the dead are all shown as unconsenting subjects of intrusive cameras. We see Edgar Degas emerging from a public toilet in Paris, Jackie Kennedy jogging in Central Park and Paris Hilton crying in the back of a car as she returns to jail on a drink-drive charge. Some might argue that the relationship between celebrities and paparazzi is mutually reinforcing, but what of an anonymous blind beggar unaware of being photographed as she appears to stare directly into photographer Paul Strand’s lens, or the unknown victim of a hotel fire documented by Marcello Geppetti as she falls to her death from a fourth-floor window? Do they deserve more protection?

Photographers will always face threats from those who expressly do not want their pictures taken, or hostility from those who feel they have overstepped unspoken moral guidelines. And in an increasingly litigious era we can expect further battles over the right to take photographs in public. But if photographers have to rely on model release contracts and posed portraits to document the world we live in, they will be contributing only to the manufacture of a stage-managed, air-brushed future. We depend on them to immerse themselves in the confusion and alienation of public life and hold up a mirror to the kind of societies we are making for ourselves. To do so they must retain the right to photograph in public places, even if the results are not always pretty.

Shizuka Yokomizo on her Stranger series 1998–2000

My motivation for Stranger came from running around London in a car with a ridiculously huge telephoto lens, trying to glimpse unsuspecting people through the windows of their flats. I felt absurd and increasingly frustrated by the one-sidedness of the activity. Aside from the ethics of what I was doing, it was important for me that the subject, a stranger, made eye contact with me while I was photographing. I realised that I needed these people to look back and recognise me equally as a stranger. So I decided to use the format of a simple anonymous letter, which contained the possibility of agreement and time to contemplate taking part (as compared with the speed of a more opportunistic photography), but also maintained the distance (perhaps suspicion) that is part of being strangers.

The division between public and private has changed massively over this time period for many reasons. And taken as a whole, this is much more significant, I think, than cultural differences. Having said that, when I started making this work (in 1998) I don’t think I somehow really could have had a sense of the private. I was rather exposed, and not settled culturally. More recently, I almost feel that I have only a private life, as I live slightly reclusively. I was not particularly interested in an ethnographic aspect. But of course there were noticeable characteristics in each city and a different sense of living. Psychological differences that were materialised in the architecture of security, for example. In spite of these details, what I looked for was localised experience, in terms of a basic human encounter as I had set it out, which I consistently found to be rather surreal and I felt was a unique frame between two people. I suppose I go through a kind of agonising conceptual process when creating work. I often seem to find myself starting with types of ‘what if?’ questions, which I try to settle myself around to begin to investigate.

I do emphasise the moment of exchange with the subject in my work, and not everything that happens is under my control. There are always unexpected elements in the nature of how I work, and these are very important. What is seen and what is image is also important, but so too is understanding the image as composed out of a situation and embedded with these other aspects that inform it. So the visual construction of a tableau is something that is altogether too controlling for me to identify with. The latest series features photographs of female prostitutes, focusing on their bodies. The format has been quite straightforward where I propose my idea and agree a fee, similar to that of a usual client. We take care to keep identities hidden and I photograph them in their working environment. We meet again so that they can see and agree the outcome, and in some cases I ask them to kiss the surface, leaving the mark of their lips.

I suppose that it is the proposed closeness to another individual in sex work, often a complete stranger, that interests me to begin with. As people who trade in actual sexual intimacy, yet are relatively hidden from view, they also contrast with the vast amount of commercial imagery generated around sexual desire. Along with this is the general view that such images (and indeed the image of attraction) constitute a powerful medium of this desire, yet the photograph that documents the human exchange, no matter how explicit, is somehow impossible. So the body of a sex worker seems to me to be a kind of interface or surface where the image disappears. Living in a world where images greatly affect my perspective, value judgments and emotions, the bodies of sex workers suggest a way to work out the anatomy of images and to understand what the image actually does.

Chris Verene on Camera Club 1995–8

In the mid-1990s I sought out photography clubs that advertise (mainly in newspaper classified columns) for aspiring models, offering them the chance of a career breakthrough. Usually called ‘camera clubs’, they have been in the US since the 1940s and are often seen as groups of male photographers huddled around swimsuit models in studios and on beach locations – eventually earning them a somewhat negative reputation.

My project sought to document the photographers who join a club to gain access to women willing to pose in lingerie, swimwear and the nude. I joined these clubs in a number of American cities and surreptitiously made pictures of the men and their equipment while the models distracted them. I also conspired with a female friend who applied as an aspiring model. Together, we found that they were never a real route to becoming a fashion model, and such promises were often offered in lieu of payment.

These clubs, and my project as a whole, pre-date the internet and the advent of digital photography. Today, the camera club mentality has become web-based. The digital age has created a much larger group of amateur photographers who masquerade as serious professionals via layers of internet appearances and identities. Additionally, technology is such that images made by unskilled photographers appear quite slick, using instant digital cameras and auto-retouching tools.

The Camera Club project is unstaged, and is a real document of how the clubs truly function. It stands as a caution to young women, suggesting that they be careful who they trust when taking off their clothes for pictures, and that they should not always believe the stories such clubs tell.

Chris Verene

Untitled (Red Back) 1997

C-type print

50.8 x 61 cm

Courtesy the artist © Chris Verene

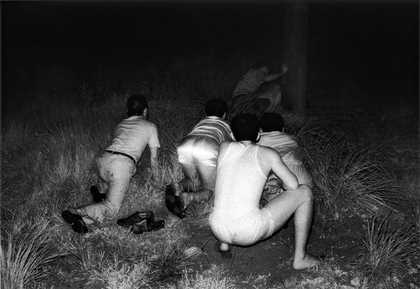

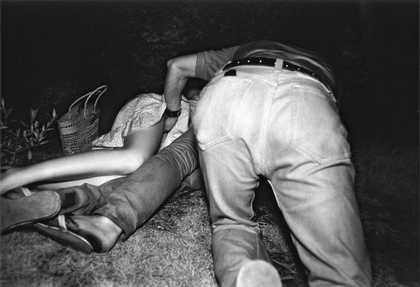

Kohei Yoshiyuki

Untitled 1971–9

All from the series The Park

Gelatin silver prints

40.6 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York © Kohei Yoskiyuki

Kohei Yoshiyuki

Untitled 1971–9

All from the series The Park

Gelatin silver prints

40.6 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York © Kohei Yoskiyuki

Kohei Yoshiyuki

Untitled 1971–9

All from the series The Park

Gelatin silver prints

40.6 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York © Kohei Yoskiyuki

Kohei Yoshiyuki

Untitled 1971–9

All from the series The Park

Gelatin silver prints

40.6 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York © Kohei Yoskiyuki

Anton Corbijn on Kohei Yoshiyuki’s The Park series 1971–9

I had not been aware of Kohei Yoshiyuki’s work until I saw a review of his series The Park about two years ago, which was accompanied by a photograph that caught my eye immediately. The infrared grittiness appealed to me, but also the image of people’s backs in a leafy environment in darkness. It seemed that the picture was that of a documentary photographer, but I couldn’t tell straightaway what was being documented. It was an odd image; what did it show? A frozen tension perhaps. I even felt that it had something forbidden about it, something I understood only after reading the review. This revealed that in the 1970s the photographer discovered that couples used parks in Tokyo to make out and that this was known to some men who loved to observe the intimate situations from close range – sometimes close enough to touch the couple. Kohei had used infrared flashbulbs so as not to disturb the scenes in front of him, making the photographs incredibly realistic and thus quite unsettling to view.

For starters, the images are far more erotic than most porno photographs, feeding through an (unfulfilled) desire to discover details about other people’s sex lives. There is something left to discover, something not shown, which is rare these days where everything is being documented and mystery has all but disappeared. But that is not the real essence of Kohei’s pictures. They deal more with voyeurism than with sex, and that topic makes them so incredibly interesting for us viewers, as we are voyeurs too. Though we are not in the photographs, we are right behind these people, trying to watch over their shoulders. The voyeurs are captured, but in a way so are we. Perhaps that is the eternal position of a photographer?

Jules Spinatsch

Temporary Discomfort Chapter IV, Pulver gut World Economic Forum WEF, Davos-CH 24 January 2003.

Network-Camera A: Promenade, Congress Center North and Middle Entry, Kurpark 2,176 still shots from 06.35 to 09.30

Courtesy the artist © Jules Spinatsch

Christian Frei on war photography

All war photography is the cynical exploitation of horror – or is there anyone who doubts this? Twelve years ago, when I first started to research my documentary feature War Photographer, numerous friends and colleagues were openly astonished. Although hardly anyone had any real idea of the daily routine and work of a war correspondent, almost everyone I told about my project had a clear, fixed, fairly poor opinion of their job. I soon realised that war photographers have a worse image than mercenaries. In the face of such horror, how can anyone care about exposure times?

Of course it is only natural that the ethos of people chasing pictures in war zones is the topic of critical reflection and discussion. But I was taken aback at how the image of war photography is met with almost automatic prejudice, rather than curiosity. I found myself wondering where it came from. Most of us have never been to war. Hardly any of us knows the stultifying nature of daily life in conflict zones. The boredom. The waiting. No. The picture we have of war is all about action. War on the big screen and on television? It’s filled with excitement, adventure, heroic deeds. And Hollywood is only too happy to promote the cliché of ‘adrenalin junkies’ who can’t live without the thrill of dicing with death. And then there are the cynical correspondents, chasing the best angle, drinking the same whisky as the troops, going to the same brothels… and heartlessly shooting pictures. For centuries visual artists reduced war to adventure and heroic exploits. War paintings were pathos and propaganda, until Francisco de Goya struck out on his own with his etchings that laid bare the awfulness and horror of war. And as I embarked on my documentary, my aim, too, was to get below the surface. How do you go about presenting a meaningful, visual account of the ever more complex, ambiguous reality of war-like conflicts? Who are these people who make a living from images of suffering, death, violence and chaos?

Sophie Ristelhueber

Eleven Blowups #1 2006

Digital colour print

Courtesy the artist © Sophie Risetelhueber

James Nachtwey once bemoaned the fact – in conversation with me – that war photographs can show only what a picture can show. But real war, ‘my God’, that was another matter altogether. So what was real war, I asked. The noise, when a house is pulverised, the stink of dust, blood, rotting vegetables and corpses, he said. ‘The pictures I take become part of the eternal archive of our collective memory.’ He doesn’t just want to capture sensational moments on film, he wants to make pictures that will last. Studies of human behaviour in extreme situations. Nachtwey believes that strong, nuanced images can change our view of a war or the world. Some critical voices dismiss statements of that kind as naïve self-promotion. They prefer to take the view that the impact of war images on politics and public life is overestimated and that, if we are to be honest, the real motivation for taking pictures in war zones is ultimately no more than a fascination with war itself. There is nowhere else that people are so vile and evil, nowhere else that they are so magnificent. War brings out all that is most terrible and most wonderful in us human beings. Does that mean the people who take pictures of it are voyeurs? Or are they just witnesses? The stigma of voyeurism that taints the reputation of war photographers culminates in the accusation that they must feel some kind of pornographic lust as they shoot their close-ups of the suffering and death of other people, of complete strangers. And they have to do penance for this lust.

The South African photographer Kevin Carter won a Pulitzer Prize in 1994 for his picture of a half-starved girl in the Sudan with a vulture nearby, ready to strike. Two months later Carter took his own life. The vulture was hunting down the starving child. The picture hunted down the photographer. And his critics took smug satisfaction in the fact that he could no longer live with his guilt. He should have rescued the girl, instead of exploiting the situation for himself. This indictment stems from a lack of information. Photographers don’t roam around until they happen to stumble on a starving human being whom they refuse to help because they are too busy coldly releasing the shutter. As a rule photographers travel with teams from aid organisations. The team members provide the aid, not the reporters. The dilemma ‘help or take a picture’ doesn’t even arise. But there is a different dilemma. Not everyone who is starving necessarily looks as though they are starving. Undernourishment does not always come across in a photograph. So some photographers specifically set out to find ‘skelleties’, extremely emaciated people who are starving. But that has nothing to do with lust. The photographer trying to concentrate the complexity of a given situation in one ‘strong’ image is attempting to help to raise awareness. Which would ultimately bring change. And he does this in the knowledge that there is immense pressure to create an image that will stand out from all the rest. And if he carries out his work responsibly and with respect, then that moment of ‘dark triumph’, when the tragic reality in his viewfinder takes on visible meaning, is not amoral, it is essential.

In 1946, when the journal DU reported on the consequences of war in Europe, the cover picture was an image by the Swiss photographer Werner Bischof. It showed a close-up of the scarred face of a boy. Many readers were outraged and sent the issue back by return to the publishers; one wrote that it was a terrible picture, an aberration of good taste, and would the editors in future please go back to reproductions of beautiful works of art?