Andy Warhol illustration for The Little Red Hen (1958) made for Best in Children's Books, published in 1958

Courtesy Knopf Doubleday Publishers

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2010

In his book The Elements of Drawing (1857), John Ruskin encouraged artists to try to recover what he called the “innocence of the eye”, to represent nature with the freshness and vitality of a child, or of a blind person suddenly restored to sight. “A child sees everything in a state of newness,” reiterated Baudelaire in The Painter of Modern Life (1863), “genius is nothing more nor less than childhood regained at will.” Subsequently, many artists tried to scramble academic convention by embarking on experimental regressions to an imagined childhood state of visual grace. Monet and Cézanne, for instance, sought to re-create the Damascus moment, conveying a structured idea in paint of the sensory explosion of first sight. In 1904 Cézanne told Émile Bernard: “I would like to be a child.”

An interest in children’s art would seem a logical outgrowth of this empiricism, but it was only in the craze for primitive art in the first decades of the twentieth century that artists began to look at children’s art seriously. In an attempt to purify art of its fin-de-siècle decadence, they looked to primitive cultures, considered in the condescending language of the time to be cultural throwbacks to the “childhood of man”; primitive art was often compared with the crude artwork done by children, who were praised as homegrown noble savages. Many of the century’s greatest artists – Kandinsky, Klee, Matisse, Picasso, Miró and Dubuffet – had sizeable collections of artwork by children. They studied and imitated the spontaneous and wilful distortions of children’s pictures as though, like dreams, they offered a royal road to the unconscious.

Consequently, modern art was often – and still is – dismissed with the cliché, “a child could have done it”. As Jonathan Fineberg shows in The Innocent Eye (1997), far from being offended by such comparisons, Expressionists, Cubists, Futurists and members of the Russian avant-garde often played up the parallel and frequently exhibited their work alongside the art of children: in 1908 Kokoschka’s work was first shown next to children’s doodles; between 1912 and 1916 Alfred Stieglitz put on four exhibitions devoted to children’s art at his legendary 291 gallery in New York; in 1917 and 1919 Roger Fry showed artwork by children at the Omega workshops; and the 1919 Dada exhibition in Cologne included infantile scribbles displayed next to artworks by Max Ernst and his colleagues.

Artists were not just influenced by the “primitive” nature of children’s art, as if childhood were itself a dark continent that was completely other to them, but by the progressive educational techniques that some of them had experienced as children. The idea of childhood as a domain of innocence and freedom was an eighteenth century invention, stemming from Rousseau and Locke, who both wrote treatises on education (before then children were considered mini-adults). In Inventing Kindergarten (1997), Norman Brosterman argues that the pedagogical tools that were used for teaching creativity in the second half of the nineteenth century, which built on these romantic ideas, might be interpreted as laying the ground for geometric abstraction in art. He convincingly shows that the twenty beautiful “gifts”, or art toys, used by the German educator Friedrich Froebel to teach children an appreciation of patterns and forms were the building blocks of modernism. Braque, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Klee, Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright all went to kindergarten schools and many of them explicitly acknowledged this debt.

As well as feeding creatively off children’s art, aspiring to children’s conspicuous lack of technique and supposedly easy access to the unconscious (so as to try to appeal to the inner child in all of us), many artists made artworks especially for children. In so doing they often sought to reflect back some of the ocular innocence and primitivism that they admired in child art. These creations – designed to be touched and played with, much as African fetishes were made to be used as well as looked at – are perhaps best considered as philosophical toys, like Froebel’s gifts, rather than artworks: they taught an idea of art that valued spontaneous expression and play above everything else. Those toys that survived their owner’s childhood games are poignant relics that embody the utopian expectations the avant-garde projected on to children.

In 1902 Paul Klee, looking for frames in his parents’ storage, stumbled across a cache of drawings he’d done between the ages of three and ten. In a letter to his fiancée he described them as “the most significant [I have made] until now”. He had just returned from four years of art school in Rome, but all his academic training seemed futile when faced with the emotional rawness of these early efforts. He included eighteen of the drawings in a later catalogue of his work, skipping over almost all the art he did in the interim years before their rediscovery. Works such as Girl with a Doll 1905, in which we see Klee in nostalgic dialogue with his juvenilia, were self-consciously executed, he acknowledged, “in a children’s style”.

In 1907 Klee had a son, Felix, and as he grew up he kept and displayed many of his “primitive” works; when people compared Klee’s paintings dismissively with children’s (“mad, infantile scrawlings”, according to one reviewer), he would reply: “The pictures my little Felix paints are better than mine.” Klee described the work of the Blauer Reiter (Blue Rider) group as returning to the “primitive beginnings of art” and celebrated the way these painters looked for authenticity and inspiration “in ethnographic collections, or at home in the nursery”, just as he did. In Tent City with Blue River and Black Zig-Zag Clouds 1919, he copied almost exactly the bold outlines of one of his twelve-year-old son’s paintings.

This chain of influence turns full circle in the toys Klee made for his son. These include ships, a train station made out of cardboard and 50 hand puppets, of which 30 remain. His creation of this grotesque cast – Kasperl and Gretl (Punch and Judy), Death, the Devil, a policeman, a crocodile – coincided with his first experiments with sculpture and, as with artworks such as Head Formed From a Piece of Brick Smoothed by the River Leche 1919, the puppets incorporate found materials: a horseshoe, a nutshell, a matchbox, an electric plug. Self-Portrait, for example, which shows the artist with huge eyes, a goatee and fur hat, is fashioned from two beef bones covered in plaster and clothed in a worn piece of grey cloth cut from one of the artist’s old suits. The figure of the devil is made from a discarded pigskin glove, two fingers fashioned into horns, and has a brass hoop through its nose. In 1921, when the fourteen-year-old Felix became the youngest pupil at the Bauhaus, he performed satirical shows there with these puppets (he later became an opera director). His father made the backdrops, Felix recalled of the merging influences, from pictures “taken from the Blauer Reiter”.

The German-American painter Lyonel Feininger, who was associated with the Blauer Reiter group and designed the cover for the 1919 Bauhaus manifesto, was also a passionate toy maker. His masterpiece was Toy Town, made for his three sons and added to every Christmas: “The time,” he said, “for my periodic craze for making toys.” It’s composed of, in one of his sons’ descriptions, “gothic, broken-backed, cramped and colourful, gable-fronted [buildings], with overhanging upper storeys, huge chimneys and steep roofs”. This crudely carved Expressionist stage set, the houses of which are no more than a foot high, is populated by lumpen, legless wooden figures with knobbly faces and peg noses – a fisherman in a sou’wester with a huge pipe, two Jesuit priests with towering hats, a German policeman with spiked helmet, their expressions painted with the brutal economy of a skilled caricaturist.

“The toys an artist has fashioned may serve to gain an insight into the formal ideas of their creator,” wrote Feininger’s son. “The ‘real work’ of each one of them has a play-like grace and ease, and in the ‘toys’ we find enough seriousness to remind us of the gravity of children’s play.” Feininger’s “excursions into the gamesome world”, as his son called his toy making, not only offered his children tools for their imagination, but fed into the artist’s “real work”, serving as experiments in geometry, colour and space. Indeed, Toy Town is like a three-dimensional version of one of Feininger’s paintings.

In 1913 one of the toy trains Feininger made for his sons so impressed a Munich manufacturer that he tried to put it into mass production (only the prototypes were built before the outbreak of war). A few other artists made toys for the mass market. The Uruguayan Joaquin Torres-Garcia, the founder of Constructive Universalism, designed a line of toys when he was a struggling artist in Paris after the First World War. In 1920, after he moved to New York, he set up the Aladdin Toy Company to manufacture his “juguetes transformable” – comic short-legged figures, candy-coloured houses, cartoonish steamships and a menagerie of animals that came as a jigsaw of pieces that could be stacked and mixed to create different modular forms. They were educational toys that echoed the abstractions in wood he was making at the time, rough-hewn versions of his friend Mondrian’s canvases. In the 1920s Alexander Calder also designed a colourful line of rocking elephants and zebras, and seals and frogs that would move about as you pulled them across the floor. While few artists considered their toys part of their “real work”, Calder was unashamed about the connections between art and play: he exhibited his circus in a suitcase, created in Paris between 1926 and 1931, alongside his wire sculptures and mobiles. There is a film of a 63-year-old Calder directing his kinetic sideshow, skilfully manipulating his 70-odd performers in a comic procession of toys: wire acrobats and tumblers, clowns, a crank-operated belly dancer, water-spurting elephant, lion tamer, sword swallower, lasso-wielding cowboy and knife thrower – each animated figure constructed with a witty, handmade charm. In Calder’s big top theatre, as in all philosophical toys, we see the boundary between art and play dissolve: homo sapiens becomes what the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga dubbed homo ludens, “man the player”.

According to Elizabeth Turner, in an essay on Calder’s drawing manual for children, Animal Sketching (1926), which provided studies for his wire circus constructs, the artist was deeply influenced by the psychologist James Sully’s Studies of Childhood (1896). In the field of revolutionary theory, Sully was one of the first to draw parallels between children’s art and the art of “primitive” cultures: “May we not say that the impulse of the artist has its roots in the happy semi-conscious activity of the child at play, the all-engrossing effort to ‘utter’, that is, give outer form and life to an inner idea, and that play-impulse becomes the art-impulse (supposing it is strong enough to survive the play-years) when it is illuminated by a growing participation in the social consciousness.”

In 1907, the year he first visited the Trocadéro ethnographic museum, Picasso made a fetish doll, with nail heads for eyes, for his cleaning lady’s daughter. The young girl was apparently frightened by his austere, totemic gift. That year Picasso also traded a picture with his rival Matisse. The latter’s highly schematised portrait, Marguerite 1906–7, was influenced by his observations of his six- and seven-year-old sons’ drawings, and Picasso was, his biographer John Richardson remembers him saying, “very curious to see how Matisse had exploited his children’s instinctive vision”. Picasso also acknowledged how Matisse’s portrait inspired the central figures in his primitivist masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907.

Picasso was fascinated by children’s art. He felt that his father, a professor of drawing, had prematurely pushed him into an academic style and he sought to regain the youthful exuberance that was sacrificed. In 1956, during a tour of an exhibition of children’s art, Picasso told Herbert Read: “When I was the age of these children, I could draw like Raphael. It took me many years to learn how to draw like these children.” There are several photographs of him observing his four children drawing, an expression of rapt attention on his face, and sometimes he indulged in collaborative doodles. “It’s surprising,” he said, “the things that come from their hands – they often teach me something.” Picasso made hand-painted dolls for his eldest daughter, Maya, who is depicted holding one in his 1938 portrait of her. He would also fashion for Maya and his son Paolo clever little paper cut-out figures – on one occasion he made them clowns and commedia dell’arte characters that they could play with in a miniature theatre he created out of an empty Gauloises packet. In 1946 Brassaï photographed a selection of Picasso’s whimsies for Cahiers d’Art: “Little birds made of tin capsules, of wood, or of bone; a thrush made of a piece of wood, a bone scoured smooth by the ocean, which Picasso had transformed into an eagle’s head… numerous silhouettes, cut or simply torn with the fingers out of paper or cardboard, are a sheer delight. Usually, he used paper napkins or cigarette packets. Among the countless things are many animals: fish, foxes, billy goats and vultures; and also satyr’s masks, children’s faces and skulls.”

In the late 1940s Picasso had two more children with Françoise Gilot, Paloma and Claude, and he made them similar toys. He whittled Paloma a series of wooden dolls from her building blocks. They stand to attention, like objects in an anthropology museum, their painted faces transforming them into chubby-faced skittles. Sometimes he used his children’s toys as found objects that he ingeniously incorporated into his own artworks, as he famously did the toy cars his dealer gave Claude in Baboon and Her Young 1951.

Matisse titled his 1950s retrospective ‘Looking at Life with the Eyes of a Child’. “The artist,” he wrote, “has to look at everything as though he saw it for the first time: he has to look at life like he did when he was a child and if he loses that faculty, he cannot express himself in an original, that is, a personal way.” Picasso’s later work, informed by his study of his own children’s art, was increasingly expressionistic, and he reinterpreted art history – making versions of Velázquez’s Las Meninas 1957 and Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe 1960 – by imagining the canon as though through a child’s eyes. His efforts attracted predictable criticism: in the 1960s John Berger accused Picasso of being “reduced to playing like a child… condemned to paint with nothing to say”.

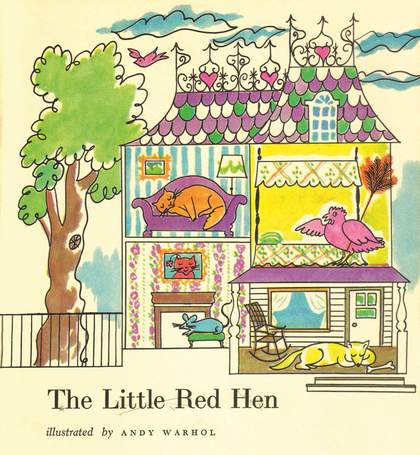

In 1983 Andy Warhol exhibited 128 paintings made especially for children at his European dealer Bruno Bischofberger’s gallery in Zurich. Though they aren’t toys in themselves, they are paintings of toys – their imagery taken from the boxes of vintage and wind-up toys he collected. Most of the silkscreen Toy Paintings – a drumming panda, an airplane, a parrot, a spaceship, a police car, a monkey and a helicopter – are composed of three bold colours, overlaid in such a way as to make it seem as though they should be looked at through 3-D glasses. They were also published as a Pop Art board book, and hark back to the artist’s earlier career in the late 1950s as a children’s book illustrator (he illustrated several volumes for the Doubleday Book Club).

Warhol’s mini-museum, one big toy, was as much a playscape as the sculptural playgrounds Isamu Noguchi designed for New York and elsewhere. The Toy Paintings were exhibited as a small version of Warhol’s 1971 Whitney retrospective, where electric chairs and Marilyns were shown against wallpaper depicting a field of cows that seemed to mock the viewer’s cud-chewing ruminations. In Zurich he substituted the cows for a shoal of fish, which sparkle against a blue background and all swim, mouths open like windsocks, in the same direction. Adults had to squat down to look at the canvases which were hung at eye level for three- to five-year-old children. (An entry fee was charged for adults not accompanied by a child under six, the money going to a children’s charity.) After he exhibited the toy series, Warhol began collaborating with Jean-Michel Basquiat on a series of canvases. Apparently Bischofberger had the idea for this partnership after his four-year-old daughter worked with Basquiat on a painting, Untitled 1984. When asked which artists he admired, Basquiat said: “What I really like and has influenced me are works by three- to four-year-old children.” (One of Warhol’s earliest self-portraits, The Lord Gave Me My Face, But I Can Pick My Own Nose 1948, is also deliberately childish: he sticks an Art Brut finger up at painterly expectations.) In one of the joint works Warhol did with Basquiat, as if in reference to this fact, Warhol included a spaceship from the toy series.

In 1983 Basquiat hired an eight-year-old, Jasper Lack, who he paid twenty dollars a day to paint motifs in his paintings: a rocket-like Empire State Building and a fishing rod with an oversized hook. Basquiat, like all the avant-garde artists who had been absorbed by children’s art, could only emulate the unselfconscious naiveté of children, which was no match for the real thing. In 1986, at his exhibition at the Mary Boone Gallery, Basquiat introduced Lack to Warhol as “the best painter in New York”.