Like an elongated Alfred Hitchcock, Francis Alÿs likes to grant himself a walk-on part in his own compositions. We normally see him from behind, and often from a distance – he is the tall, slender man trailing a ribbon of green paint behind him as he walks one of the most contested boundaries in the world, or the professorial figure in green trousers and a brown jacket receding down the gravel paths of the Casa Serralves in Porto, in a “photographic documentation of an action” that “resulted in two pebbles in my left shoe” (Untitled 2001).

His presence is unobtrusive, but it always leaves a trace: in The Swap 1995, Alÿs traded objects with commuters in the Metro in Mexico City, where he has lived since 1986. He began with a pair of sunglasses, and ended up with a small wooden dog. Yet the documented trades were not the end of the process: “The protagonist leaves the last object,” Alÿs wrote in his documentation of the event – and who knows what other swaps were triggered by its presence in the eco-system of the Metro?

Once, Alÿs stood in a city square, staring at the sky, until a crowd began to form around him. It is a truism that most people traverse the modern city in a state of concerted disengagement, preoccupied by their own concerns, and both the passivity and the intent curiosity of the static figure must have been intriguing: people wanted to see what had engaged his attention – and once he had engaged theirs, he walked away.

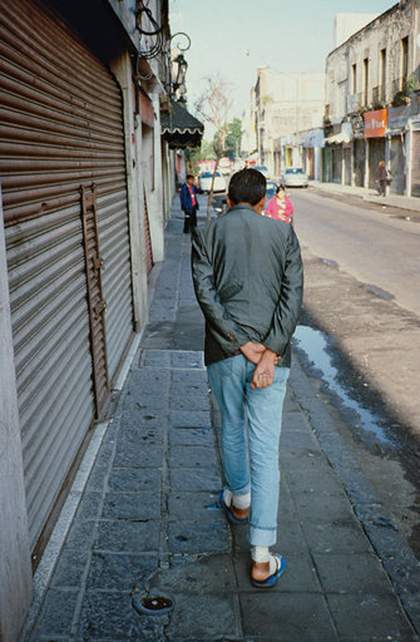

Francis Alÿs

Detail, The Doppelganger (Mexico City) 1999–present

Thirteen framed photographs and text

© Francis Alÿs

Francis Alÿs

Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing) 1997

Photograph of an action

© Francis Alÿs

On other occasions, he reverses the process – instead of standing still and letting a crowd form around him, he picks out a passer-by who looks like him, and follows him through the city. The piece is called The Doppelganger 1999–the present, and the accompanying notes provide a template for those who might choose to imitate his example: “When arriving in a new city, wander, looking for someone who could be you. If the meeting happens, walk beside your doppelgänger until your pace adjusts to his/ hers. If not, repeat the quest in the next city.”

The strength of the idea is its simplicity: Alÿs is a kind of story-teller, and his stories have a fabular quality that makes you want to tell other people about them. “If the story is right, if it hits a nerve, it can propagate like a rumour,” he has said. “Stories can pass through a place without the need to settle. They have a life of their own.” According to the art critic Lynne Cooke, Alÿs is contemplating creating a work “which takes the form of a rumour”.

Francis Alÿs

Detail, Amulantes II (Pushing and Pulling)1992–2003

Slide projection

© Francis Alÿs

Francis Alÿs

The Green Line (Sometimes doing something poetic can become political and sometimes doing something political can become poetic) 2005

Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Francis Alÿs

The essay in which she mentioned it was part of the work; so is this article, and so is anyone who decides to pass the story on. Given his apparent desire to involve the public in the production of his work, it is not surprising that he has a tendency to recede into the background. On 23 June 2002, nine months after the events of 9/11 which sent New York into a state of collective mourning, he created a work that imitated the religious processions he had often witnessed in his adopted home of Mexico. The Museum of Modern Art was moving from its Manhattan base to a temporary home on Long Island City in Queens, and Alÿs organised a group of porters, accompanied by a Peruvian band, to transport replicas of iconic works of art in its collection through the streets of the city. In keeping with its quasi-religious spirit, The Modern Procession was staged on a Sunday morning. It was a sociable, celebratory event, and yet Alÿs played little part in it: “Really, when it comes to the reality of the battlefield, my long-time friend and collaborator Rafael Ortega takes over… He is the eye and the voice to people. I withdraw, I follow the ‘cortege’ and watch,” he said in a conversation recorded in a book published to document the event. As the procession crossed the Queensboro Bridge, Alÿs felt that the participants had lost their self-consciousness: “The path became narrower, people got closer, touching shoulders, it got windy, you nearly felt vertigo, and there was the forever-now tragic beauty of the New York skyline. Then maybe that little magic touch happened, the one you can’t plan… The procession had taken its own course and life, and I became just another participant. And that is when I started looking at it. And enjoying it.”

The Public Art Fund’s book supplies further evidence of his tendency for self-effacement: its inside front and back covers contain 144 passport-sized photographs of people involved in the procession, and it takes some time to spot the image of the man who set the project in motion. Even when he is physically present, he has ways of making himself absent: Alÿs once spent a week walking through the streets of Copenhagen under the influence of a different drug every day. “The journey was followed by a period of depression,” he wrote, wryly, in his notes to Narcotourism 1996. “I understood it, but could not help sinking into it.”

Francis Alÿs

The Nightwatch (still) 2004

Single-channel or twenty-monitor video installation

© Francis Alÿs

Francis Alÿs

The Ambassador 2001

Photograph of an action, Venice

© Francis Alÿs

On occasion, he has co-opted animals to act as his familiars. He released a fox in the National Gallery (The Nightwatch 2004) and a mouse in the largest collection of contemporary art in Mexico (The Mouse 2001). In a work called The Ambassador, he sent a peacock to represent him at the Venice Biennale of 2001. Given Alÿs’s apparent desire to produce work which acquires its meaning through engaging other people, the gesture might be seen as a way of subverting the Romantic cult of the artist as sole begetter of the artistic enterprise. Yet it has more specific meaning, as well: Lynne Cooke says that “Alÿs’s witty lampoon” contains “sly echoes of Aubrey Beardsley and other late nineteenth-century aesthetes, dandies who not only prized this exotic animal, but cultivated a mode of public posturing as integral to a wilfully decadent lifestyle they considered an art form in its own right”.

Yet unlike the nineteenth-century flâneurs, who provide one model for his incessant walks and strolls around the city, Alÿs is not a passive spectator, and he does not encourage passivity in others: If you are a Typical Spectator, What you are Really Doing is Waiting for the Accident to Happen runs the title of a 1996 video work, in which he filmed himself kicking a bottle around a square in Mexico City, until he wandered into the road, and got hit by a passing car.The awareness of the impossibility of remaining disengaged seems to inform political works, such as Politics of Rehearsal 2005–7. The video begins with an excerpt from a speech by Harry S. Truman extolling the necessity of developing Latin American countries as a way of insulating them against the lure of Communism, and yet the rest of the film illustrates the futility of the aim. It is shot in a dark bar in New York, where a pianist, a singer and a stripper are rehearsing: the musicians keep stopping and repeating certain phrases, which means the conclusion of the stripper’s act is constantly delayed, while on the soundtrack, a man discusses the impossibility of Mexico achieving the desired state of development. As Alÿs’s introductory title explains, the video is a “metaphor of Mexico’s ambiguous affair with modernity, forever arousing, and yet always delaying the moment it will happen”. The artist himself appears in characteristically low-key mode, as the sound man with a boom, drifting in and out of shot.

Francis Alÿs

Politics of Rehearsal (still) 2005–7

© Francis Alÿs

Other works are less susceptible to interpretation. When Alÿs walked around Jerusalem, trailing a ribbon of green paint behind him, he was following the so-called Green Line, which was drawn on a map by the Israeli Minister of Defence Moshe Dayan at the end of the Arab-Israeli war of 1948–9. It marked the respective positions of Israeli and Arab forces in the final ceasefire, and it has served as a highly permeable boundary between Israel and the West Bank ever since. The piece was called The Green Line (2004), and it fell into a group of works with a longer title that summed up one aspect of Alÿs’s philosophy: Sometimes doing something poetic can become political, and sometimes doing something political can become poetic 2005. “Can an artistic intervention truly bring about an unforeseen way of thinking, or is it more a matter of creating a sensation of ‘meaninglessness’, one that shows the absurdity of the situation?” Alÿs has asked. “And can an absurd act provoke a transgression that makes you abandon the standard assumptions about the sources of conflict? Can an artistic intervention translate social tensions into narratives that in turn intervene in the imaginary landscape of a place?”

In 2005 he enlisted a group of 500 Peruvians to shovel sand along the crest of a dune near Ventanilla, a neighbourhood of shanty towns outside Lima. Their instruction was to shift the dune by several metres: in one sense, it was an exercise in futility – the change would be impossible to measure and, in any case, the chances are the wind would instantly reverse it – yet Alÿs has said that the exertion produced “some kind of social sublime”. The 2006 series of works called Bridge seems to occupy the same ambiguous territory: his attempts to create a line of boats across the Gibraltar Straits, between Tangier in Morocco and Tarifa in Spain, and another between Florida and Cuba, hardly qualify as “bridges”, since they were no more solid than the water on which they rest, and fail to connect one shore to the other, yet the communal effort in the face of inevitable failure, and the attempt to forge a link between areas separated by social and political divides no less bridgeable than the sea, is paradoxically uplifting.

In 2003 Alÿs went to Patagonia to film the ostrich-like birds called nandus. “The impetus for that project was a story that the Tehuelche people used to hunt nandus by walking after them for weeks, until the birds collapsed from exhaustion,” writes Russell Ferguson. In the end, the artist “felt that his film stayed too close to a conventional nature documentary”, and instead, he made a work called A Story of Deception 2003–6, which consisted of images of the shimmering heat haze that lay at the end of the dusty roads along which he was travelling. It was, he said, the “perfect image of fuite en avant, of fleeing forwards”, constantly in pursuit of something that lies out of reach.

Every year for the past ten years, Alÿs has set off in March, at the height of the dry season, into the fields south of Mexico City, “where smoky clouds rise from cornfields burning after harvest, and swirls of ash and sand loom against the horizon”. He parks his car, takes out his video camera and runs after the tornado, hoping to catch one “as a surfer catches a wave”. The event is documented from inside and out – video and still pictures show the angular figure of the artist running across the fields and disappearing into the leaning tower of dust, while his own footage preserves the perspective from the eye of the storm. It is a characteristic intervention – perplexingly counter-intuitive, and yet inexplicably resonant, a quixotic gesture that flowers briefly into life and then fades from view as rapidly as the tornadoes themselves. It changes nothing, and yet a record of the event is preserved in photographs and films, and a story that you might choose to pass on to your friends is added to the pool of collective memories.