Although Picasso is known as a remarkable twentieth-century painter and sculptor of things and of people, there is little doubt that his ambitions as an artist reflected his art education in late nineteenth-century Spain. Throughout his career, he sought ways to be both a modernist artist and to match the grandeur, scale and public address of academic history paintings, works illustrating great events in history, scenes from the bible, or classical myths.

Working long after the great era of such painting in European art during the preceding three or four centuries, Picasso had to reinvent history painting, and to draw upon what had always been a counter-tradition, depictions of human situations conceived in poetic terms. So in 1903 he produced Life, a vaguely allegorical image of the cycle of life, and in 1905 The Family of Saltimbanques, a lyrical scene of circus folk whose anomie could stand for all kinds of contemporary experience. But his project of a modern kind of history painting only became crystallised long after these works, in 1937, with the advent of the Spanish Civil War and the highly unusual situation of a state commission from the struggling government of Republican Spain. The result, Guernica 1937, not only represented a remarkable negotiation of the competing demands of public-scale painting, an established personal practice and iconography and the politicisation of an horrific act of fascist aggression, it also transformed Picasso’s reputation.

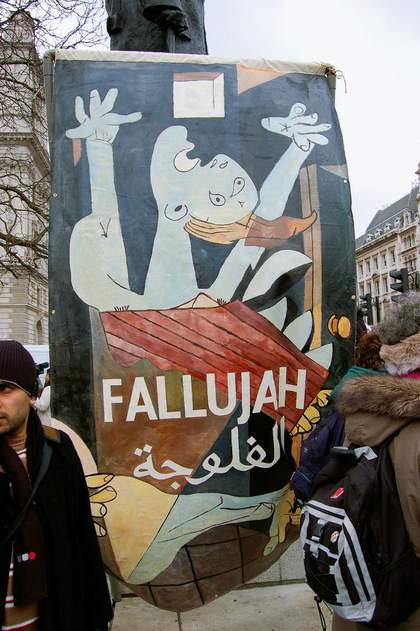

Sitting out the Franco regime in the Museum of Modern Art in New York from 1939 to 1981 (when it finally returned to Spain in accordance with the artist’s wishes), the painting became a symbol of resistance, a site of protest, a politicised image. In 1970 the Art Workers’ Coalition co-opted it for a demonstration against the US involvement in Vietnam, holding up posters showing photographs of My Lai in the museum space where Guernica hung. Since Picasso’s death the painting’s meaning has been reactivated by Spanish politics, its location in Madrid contested by Basque nationalists and its meaning for contemporary Spain tested by the activities of ETA. And the tapestry of Guernica that normally hangs outside the UN Security Council chamber acquired a charged political meaning in January 2003, masked as it was by a blue sheet for Colin Powell’s press conference on the need for regime change in Iraq. Anti-war protestors insisted on the imagery, parading cut-out figures of the painting’s screaming women through the streets of New York the following month.

But if Guernica is one of the most potent essays in history painting of the modern age, and one whose ambiguities of meaning have only enhanced its political value, the period in Picasso’s art after its creation up until his relationship with Jacqueline Roque commenced in the mid-1950s has been a problematic one for art history to accommodate, a symptom in turn of the awkwardness and over determination of his activity, both artistic and political. As an artist now made in the image of Guernica, he had to live up to the ideal of the modern political painter, something that he marked publicly when he joined the Communist Party in 1944. He might, as he told American GI Jerome Seckler in 1945, have wanted “to use a revolutionary manner of painting and not paint like before”, but he also insisted that the political dimension of his art could not be forced or consciously produced: it would simply be self-evident as a function of his intense openness to the sheer intensity and particularity of human actions.

Protesters demonstrating in London against the American air strikes in Fallujah, Iraq (2004)

© Patrick John Quinn

Gregory Sholette

Anti-Iraq war protest in New York City 2003

Courtesy Gregory Sholette

The art that Picasso made during the Nazi occupation and the pernicious collaboration that was the Vichy regime had its meaning guaranteed as a sign of “resistance” and of the idea of freedom in a series of major exhibitions staged immediately after the liberation. But once he had to function as a Communist painter, and not just as a Communist, the production of an adequate modern history painting became an urgent but impossible task.

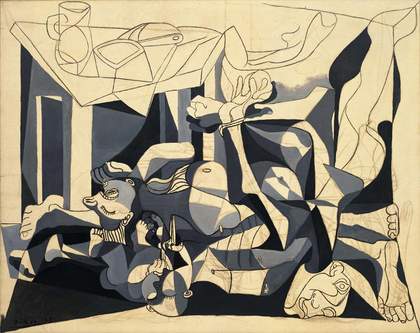

The struggle is perhaps most evident in the comparison of two highly ambitious works, one made in the complex moral moment of post-liberation utopianism, purging and reparation, and the other when international conflict was inscribed in Cold War Manichaeism, when Picasso felt the need to answer the call of a Communist history painting and to find the emotional resources adequate to an essentially remote, mediatised war. Thus, the austerity and confidently “unfinished” nature of a large canvas, The Charnel House 1945, a grisaille tribute inspired by a filmic representation of a massacre of a Spanish family but generalised to represent every pogrom and concentration camp, confronts the gaucheness of the smaller Massacre in Korea 1951. The awkwardness of the latter stems from its leaden composition, meant to recall Goya’s The Third of May 1808, and its peculiar robot soldiers executing timelessly naked women and children.

The echo of Goya signals Picasso’s strategy, developed over the next decade or so, of modelling his grander artistic statements on famous history paintings of the past, ones that could be carefully chosen to have a subtle political subtext. No one mistook Massacre in Korea for a great painting in 1951; the lack of specificity in its meaning (for which side in the Korean War do these soldiers act?) was tellingly revealed when it could be deployed against the Soviet invasion of Hungary, the Communist painting re-inscribed as anti-Communist, albeit in a manner in tune with the artist’s own reaction to the invasion. Is there something tragic, lamentable, about Picasso’s failure to produce a viable political history painting for Communism and the Communist Party’s disastrous treatment of such a prodigiously talented and celebrated party member? No doubt his many successes as a propagandist for peace, and his financial support for numerous causes and protest groups, constitute a part of the artist’s historical importance that has been largely neglected, a lack that the upcoming Tate Liverpool exhibition will redress.

Yet the problem of Picasso’s journey from Guernica to the other side of his ostentatious political involvement, a journey that arrived at the strangely expressive work now branded “late Picasso”, remains. If, from the perspective of an assessment of Picasso’s artistic achievements, his history paintings of the late 1940s and 1950s can only be judged among his weakest, it is at least arguable that the wilful resistances to the determination of the painter’s role that they expressed, and indeed the painful public humiliation that they provoked, led Picasso to find remarkable resources and means in painting and printmaking in the last decade or so of his life.