John Latham

Film Star (1960)

Tate

Kenneth Stephens, Steve James, Rachel Hedley & John Purkis on William Blake’s etchings

Four members of the public say why they donated money towards the purchase of eight hand-coloured drawings by William Blake.

Kenneth Stephens: I nursed my mother through the last years of her life. We were both drawn to art through visits to Tate. I donated to the Blake acquisition because it will be an enduring memory for me, of my mother and her love for me and Blake’s art.

Steve James: I feel a special connection with Blake’s work as I sing in a choir, the Crouch End Festival Chorus, who recently made an album with the former Kinks frontman Ray Davies, a great fan of Blake’s art. The album sported a Blake painting on its cover, so it seemed particularly relevant for me to support the acquisition.

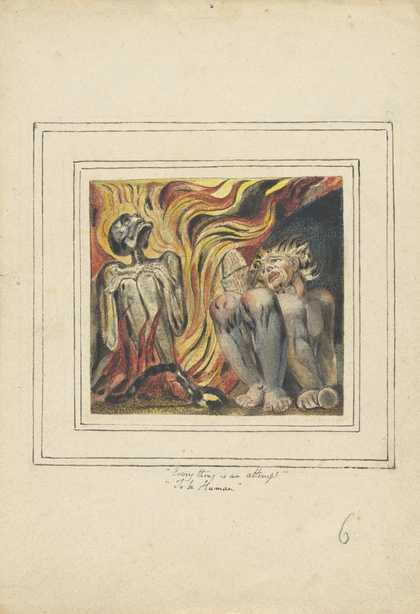

William Blake

First Book of Urizen pl. 10 (1796, c.1818)

Tate

Rachel Hedley: I’ve always loved Blake’s poetry since studying Songs of Innocence and Experience at school. I now live near Peckham Rye, where he was reputed to have seen his visions of angels, so when I heard about requests for donations to buy his etching for the nation it struck a chord. I’m really glad the campaign was successful.

John Purkis: I first visited Tate in the 1940s when I was at school, and I always went to look at the Blakes and the Palmers. There always seemed something more to be seen than appeared at first glance. Blake is an artist whose work remains full of interest for me, and though we now know far more about the background to his work in Lambeth and elsewhere, nothing can ever take away the amazing otherness and mystery in the pictures. Good old Blake: I hope I shall die singing like you.

William Blake’s eight etchings were purchased with funds provided by The Art Fund, Tate Members, Tate Patrons, Tate Fund and individual donors. They will be on display at Tate Britain in July.

John Simpson

Head of a Man (detail) c.1827

Oil on canvas

73.3 x 56.2 x 1.8 cm

Photo: Tate

Petina Gappah on John Simpson’s Head of a Man c. 1827

I don’t know whether John Simpson had a model for this portrait, whether he met a real black man who sat for him, or whether he glimpsed someone on the street whose eyes he could not forget, or whether the picture simply came straight out of his imagination. When I look at the painting, I like to imagine what its first viewers saw. Those eyes pull you in without looking at you; you cannot turn away. Did they recognise a common humanity shining from those eyes, those first viewers in the age of slavery? Did they recognise that beauty can come in this form? There is beauty in those eyes, yes, and there is a look of nobility and suffering borne with defiance.

I cannot help but think of the first two verses of H.W. Longfellow’s poem The Slave’s Dream:

Beside the ungathered rice he lay,

His sickle in his hand;

His breast was bare, his matted hair

Was buried in the sand.Again, in the mist and shadow of sleep,

He saw his Native Land.Wide through the landscape of his

dreams

The lordly Niger flowed;

Beneath the palm-trees on the plain

Once more a king he strode;

And heard the tinkling caravans

Descend the mountain-road.

The poem about a dying slave’s remembered past life of contented nobility, complete with a dark-eyed queen, kissing children, a powerful stallion and bright flamingos, was written on the other side of the Atlantic, and long after Simpson’s painting, so it cannot have influenced this portrait. There is no possibility of a direct connection, other than in the idea of the enslaved nobleman, a romantic notion that has a strong pull on the imagination. Perhaps it was necessary that those first viewers saw this man as a king in chains in order for them to understand that black slaves were people too. This is ultimately what those eyes demand; a recognition of a shared humanity.

Head of a Man was presented by Robert Vernon in 1847 and is currently not on display.

Ford Madox Brown

Carrying Corn (detail) 1854–5

Oil on mahogany

19.7 x 27.6 cm

Photo: Tate

Mary Bennett on Ford Madox Brown’s Carrying Corn 1854–5

It is the unexpectedly spontaneous quality of the brush-strokes which delights me in Carrying Corn, one of Madox Brown’s rare landscapes: the loose casualness of the paint laid on in the turnip field, half shadowy, half brilliant emerald tints; the

farm woman, a mere dash or two of paint among the rows of vegetables; the corn stacks easily brushed in with so few strokes; the mere blob of the harvester atop the cart, reflecting the intense afternoon sun of high summer.

It seems quite at variance with his usually highly finished paintings, but it perfectly conveys his excitement in surveying the brilliant summer colours when on an joy ride from cares at home with his wife Emma on a train and bus through the rural countryside to St Albans in August 1854, described so vividly in his diary. This made him aware of the simplicity and charm of his immediate surroundings. He looked for subjects about his home at the then still rural Finchley, and began three small pictures he hoped to sell quickly (The Brent at Hendon and The Hayfield are also at Tate).

Ford Madox Brown

Carrying Corn (1854–5)

Tate

This landscape looks at first sight the work of a day or two at most, but it entailed many visits to the site well into October and much work in the studio. His exhilaration gave way to despondency as the weather inevitably changed, the wheat was carted and the background trees proved troublesome. He regretted the time taken from his unfinished The Last of England, but while so dissimilar in technique, Carrying Corn has the same characteristic qualities of vitality and immediacy.

Carrying Corn, purchased in 1934, is currently not on display, but The Hayfield and The Brent at Hendon are on show at Tate Britain.

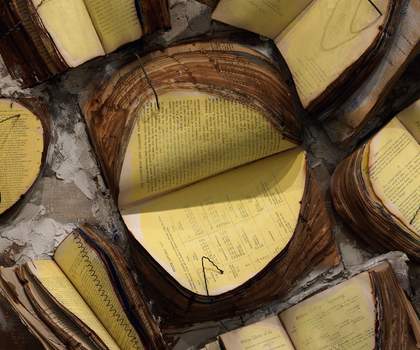

John Latham

Film Star (detail) 1960

Books, plaster and metal on canvas

160 x 198.1 x 22.8 cm

Courtesy of Lisson Gallery, London © Estate of John Latham (noit prof of flattime). Photo: Tate

Nathan Dunne on John Latham’s Film Star 1960

The book is wounded. Its yellow wings have been clipped and plastered down by a rogue librarian. I expect the pages to begin moving in an attempt at flight, but they remain still, urging me closer. Beneath the veil of yellow, words run together into spasmodic clumps. Black ant-like clumps. The sentences begin climbing over one another trying to escape the page, but get trapped in the textual traffic. I squint hard and can make out fragments of a sentence: “the”, “heavy”, “space”.

The wounded book is a butterfly. Pale and pallid. I begin to imagine that the butterfly can hear me when I speak and I say: “Butterfly. Are you sick?” and the butterfly says: “Yes. But I will soon be well.” It also makes me think of other books: Jonathan Swift’s The Battle of the Books, where a fierce contest breaks out between the Ancients and the Moderns, E.M. Forster’s Howards End, when Leonard Bast grabs on to the bookshelf and it falls on him.

The book is alive and sensual. Like a nymphet’s newly dirtied sock. It cries out to be touched or put in the mouth. It says: “Here I am, open me, crawl deep beneath my yellow wings and discover what lies beyond.” I imagine pulling the book away from its canvas and running headlong into the dark where I can rub its rough pages over my skin. Never before have I been moved to salivate over a book like Latham’s. It’s because he leaves something masked. He leaves me musing on hidden beauties. Words have been buried alive in this painting, and gazing in I can see their ghostly figures.

John Latham’s Film Star was purchased in 1966 and is on display at Tate Modern.