The default take on Fiona Banner’s work is that it’s “about” language. Given that she has made punctuation marks into glowing neons and weighty bronzes, has handwritten start-to-finish running commentaries on Hollywood blockbusters, sexually explicit films and the bodies of life models, and fashioned an ersatz alphabet from fragmented images of fighter planes, that’s not an entirely unwarranted assessment. It is, however, a partial one, obscuring the poetics and acuity of the Merseyside-born artist’s practice, whose insights arise between laterally connected points of reference. Words and how they fail us, yes, but also war, pornography and the vulnerable human body.

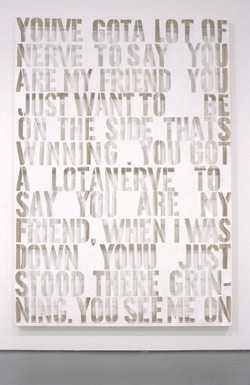

Banner has suggested that she began making art from war films because she loved them; because she wanted to figure out why they gripped her – how they could be at once seductive and repulsive; how we could hate war, but relish these movies. The result was works such as Apocalypse Now 1997, a grey haze on a vast sheet of paper which, up close, reveals itself as a blow-by-blow written description of the 1979 Coppola epic, and THE NAM 1997, a 1,000-page book offering subjective transcripts of six well-known Vietnam films. Such projects saw Banner working through her confliction, as if seeking to overmaster cinema’s dangerous power. (Indeed, all her work can be seen as a form of response to a pre-existing image or schema, an attempt to deal with its authority and ambiguities.) But a point about language arcs through these emphatically subjective, imperfect linguistic responses to a filmic experience. War itself, which begins where diplomacy and negotiation fail, is intimately tied to language and its shortfalls.

The earliest war film she found fascinating was Top Gun; in 2004 she made a word-portrait of Black Hawk Down. She maintains a glass-cased collection of newspaper images of every fighter in service (All the World’s Fighter Planes 1999–2009); she has suspended hand-made unpainted kit models of every kind of plane in service from the ceilings of galleries (Parade 2006) and, in 2007, the Tate Christmas tree; she has exhibited mirror-polished tailfins as streamlined sculpture, leaving audiences to assess their mixed feelings. If planes are an emblem in her work, it’s partly because, penetrating space and phallic in form, they reflect the subsumed masculine eroticism of battle. Given her awareness of the crossover between war and sex, it was logical when in the early 2000s she began making word-portraits of adult films (eg Arsewoman in Wonderland 2001), furthering her inquiry into how a visual experience can both titillate and repel, and what that says about us. Both war and porn, too, advertise power – which is why Banner’s consequent move into creating variations on the academic nude portrait wasn’t a complete left turn: it followed on associatively from the porn works. She chose to make word-portraits of models, often live in the gallery (eg MoMA Nude 2006), and pointedly did so while unseating the traditional male artist/female sitter dynamic.

If this seems like a diverse array of approaches, they nevertheless link together powerfully – and open on to spacious conceptual territory. Consider Bird 2006, a tailfin with a subjective description of a bird written upon it. The title suggests how the accoutrements of war are naturalised by language: the planes get called “birds” in films, and receive nature-related names such as Harrier (for the hawk). An inference arises here: that, on some unconscious level, war is an extension of nature. In some ways, one might consider it a test flight for the larger project which Banner plans for Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries, which – even taking some big tailfin pieces into account, and her sculptural full stops on London’s Southbank – will be her largest and most dramatic sculptural work to date, one in which her long-standing concerns with attraction, repulsion and the evidence of our cultural traits will be writ large.

The darkest elucidation of this work, and of Banner’s art in general, is that it is a portrait in absentia of a species where Eros and Thanatos are entwined – evidence for which is available not only in geopolitics, but in popular cinema and its clandestine cousin, porn; the history of the nude; and, in the case of Banner’s sharp, sidewinding, synoptic work, the most sensitised art of today. If this art is about language, then, it’s about what we never quite articulate to ourselves, and perhaps cannot, but really should.