Cosima Spender

How did you meet Arshile Gorky?

Mougouch Fielding

I had come to New York to study painting, from China, where I’d left my family. I had taken a boat across the Pacific and landed in Iowa city in the middle of August to study with Grant Wood, but he wasn’t there. I painted a bit in the university studios. Soon I went to New York as I was advised to go and look up Hans Hoffman, but before I got around to that I met Bill de Kooning, who wanted me to meet Gorky. He asked us both to a party, but I was a bit late and Bill forgot to introduce us. I was shy and sat down eventually next to a man who seemed to be a stranger too, just watching the others in total silence. I’d been told Gorky was a tremendous show-off by Elaine de Kooning, so I was waiting for the dancing and the singing, but nothing happened. After a bit I said my goodbyes, and at the door I was joined by the silent man I’d been sitting beside, and he said: ‘Excuse me Miss, are you Miss Magwider’. I said: ‘No, it’s Magruder, but that’s pretty close.’ He said: ‘Well Ms, would you come and have a cup of coffee with me?’ We left together laughing and sat in the nearest café.

Cosima Spender

What was your first impression of him?

Mougouch Fielding

He was tall and had marvellous dark eyes – there was something fatherly and familiar about him. I don’t know why, perhaps it was his pork pie hat that was the same as my father’s. And he was tall like my father. He asked where I’d come from, and I told him my father was in the navy on duty in China. I was twenty, and didn’t feel I had a biography. He walked me home and asked me whether I wanted to see his painting. The following night he took me to dinner, and afterwards we walked the whole length and breadth of Central Park. The next day he came to fetch me and took me to his studio on 16th Street and Union Square, all the way downtown, where I had never been.

Cosima Spender

Do you remember the first picture that he showed you?

Mougouch Fielding

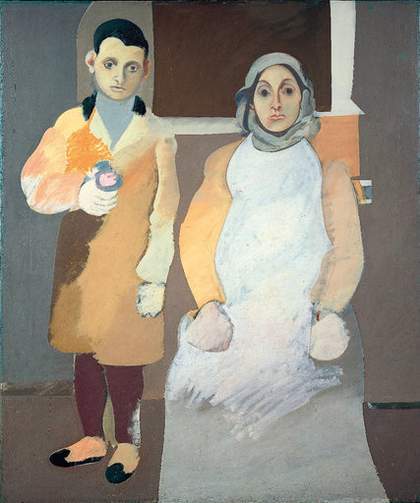

He kept all his paintings out of sight in a room and brought them out one by one. I had never seen anything like them. The first one was The Artist and His Mother 1926–36, which is now in the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the yellow version of Garden in Sochi, painted with the same very polished surface (not in the Tate exhibition).

Cosima Spender

What did he say about The Artist and His Mother?

Mougouch Fielding

I never asked him to explain exactly. Instead, he told me of this country far away where he was born, and about his early youth climbing trees and swimming and his father’s little farm by a great lake. He showed me the photograph of him and his mother that was pinned on his easel. The whole evening was magical. He asked if I’d been to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and I told him, above all, I liked the small Frick Collection. So we went to the Metropolitan and the Frick, and looked at one of his favourite paintings – the Ingres, La Comtesse D’Haussonville 1845. From that moment we were always together. We walked all over and took endless buses to Harlem and visited Staten Island and looked at museums. Gradually, I met his friends, including Isamu Noguchi and John Graham. I was overwhelmed by all he showed me – like Alice in Wonderland. I had been lost in New York and extremely lonely before I met him. New York was his city, but he was lonely too. He had a fried egg for breakfast at the ‘quick and dirty’ on the corner of Union Square, so I started to make him porridge and take care of him. I knew nothing about cooking, but he taught me. Gradually, I moved in and told my mother about him.

Wifredo Lam

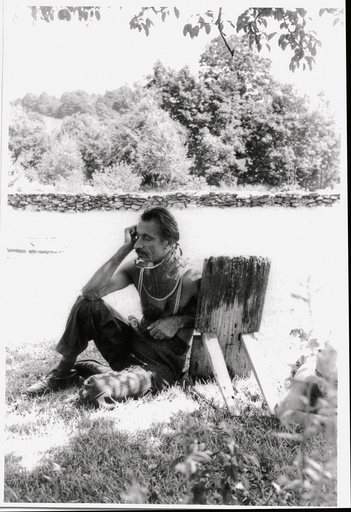

Arshile Gorky wearing an immobilisation collar in Sherman, Connecticut, July 1948

Courtesy SDO Wifredo Lam © Wifredo Lam

Cosima Spender

Did you watch him work?

Mougouch Fielding

Inevitably, since he was constantly at it; he even drew on the paper napkin in the café. He was very pleased I could speak French as it meant I could translate things from his books while he painted. He had never been to France and I had. He wanted me to paint, so one day he put a bare canvas on his huge easel and told me to help myself to his paints and brushes – he had hundreds of beautifully washed brushes standing in pots, and other little pots full of paints, straight out of the tube, so they had a little skin on the top. Then he left me to myself, and I was suddenly so awestruck and felt so totally inadequate that I couldn’t bear to dirty a brush. I was crushed. I had nothing to say and just sat and waited for him to come back. He showed me endless drawings inspired by Matisse. He had taught himself to throw his line in that wonderful way that both Picasso and Matisse did. He learned from everybody, including his friends John Graham and Stuart Davis. He absorbed many artists’ styles and made them his own. And he visited all the museums and saw everything. He did sometimes use his hands, fingers or palette knife, but on the whole he used brushes. He loved his brushes. After a day’s work he always washed them very carefully three or four times. I became part of his world and totally absorbed in him.

Cosima Spender

When did you meet Jeanne Reynal?

Mougouch Fielding

In the spring of 1941 Noguchi took us to dinner at Margaret Osborne’s house. She had a painting of Gorky’s, and there we met a wonderful woman who was to become a fairy godmother in our lives, Jeanne Reynal. Born into a very rich and socially prominent New York family, as a young woman she had met Boris Anrep, the Russian mosaicist (who did mosaics for Westminster Cathedral and in the National Gallery). She fell in love and ran away to Paris with him. Her father disinherited her and she worked for Boris in Paris until the war. Her father had just died and to her surprise she had inherited a large sum of money. She came to the studio to look at Gorky’s paintings and bought two immediately. She returned to San Francisco where she was now living and arranged for him to have a show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He hadn’t had a show for many years. The exhibition was to take place in the summer of that same year, and Isamu offered to drive us across the United States as he had some work to do on the West Coast. We all three sat in the front seat of his station wagon, with Isamu’s portfolios and sculptures in the back. The further from New York we were, the more discombobulated Gorky became. He hated the food and the monotonous big roads. Once we got to the Mississippi he felt it was a Rubicon he couldn’t cross, and he stopped the car in the middle of the bridge and wanted to walk home. I had to plead with him and he got so angry with me that he wanted to throw me into the river, but eventually I convinced him we had to go on – we had somehow to get to San Francisco.

We went to see the Grand Canyon and Isamu and Gorky both turned their backs unimpressed, saying it looked like a postcard. In Santa Fe we met a Navajo Indians expert, Oliver La Farge (Peggy Osborne’s brother), and visited the Navajo on their reservations. Here, Gorky felt some warmth and humanity: the round breast-like ovens where they cooked their bread reminded him of home. But he was horrified by their isolation. We went to see the Hoover Dam, and he felt this great river, like the Navajo, had been imprisoned. We stopped at diners and motels. He was appalled by the food – the heated-up French fries; the only real thing was corn on the cob. We stayed in Los Angeles, where Isamu had a lot of friends among the actors and directors, and swam in Malibu – and I discovered that Gorky didn’t really swim. We drove up to Big Sur. It was all so beautiful, but he wasn’t stunned – he only liked things he could get close to; he liked hills he could walk over. The mountains were not as big as those in the Caucasus and the people and their houses had no relationship with the landscape. The villages seemed heartless and all looked alike.

When we got to San Francisco, Jeanne’s life had changed – she was no longer living on a ranch in the country, but in the middle of the bustling city in the artists’ quarter, where she had a pretty little studio flat with curtains and armchairs that certainly wasn’t suitable for Gorky to paint in. We were stricken. He was totally dislocated: too far, too alien and he felt so insecure that he couldn’t even make an effort. However, the show did open, the paintings looked beautiful and people were excited and responsive, but Gorky was deeply unhappy in San Francisco and wanted to go home.

In Virginia City, Nevada, we were married by the Justice of the Peace, then went into an old bar with marvellous pictures of the founders of the city with their shovels and proud whiskers from the Gold Rush era. We drank champagne. I realised I could never leave Gorky as I was too much part of his life, and Jeanne was a great influence; she really believed in him: ‘What could you do with your life which would be better than marrying Gorky?’ When we got home to the studio it was heaven, and there was a letter from the director of the Whitney, Lloyd Goodrich, saying he must have a big Gorky painting for his biannual exhibition which was due in a few days. Gorky stayed up all that night in a tremendous excitement and worked on the dark green Garden in Sochi 1941 (now in MoMA, New York). Goodrich came the next day and loved it.

Cosima Spender

Tell me about the trip to the countryside in Virginia in 1943.

Mougouch Fielding

Once we had a baby, the enormous studio seemed far too small. My mother had just bought a farmhouse in Virginia because my father was at sea in the Pacific and my brother was a marine there too. I had to give up my job, so we decided to spend the summer with her. Gorky immediately liked Virginia. It was hilly and had a little brook. He arrived with no paints and no easel, as we couldn’t fit much into the car. All he took were wax crayons and watercolours and buckets of paper. And that’s what he feverishly worked on all summer. He cleaned up the barn and decorated it with old horse bones that he found in the fields. It was the first time that he saw the seasons in America come and go. We got there in the spring and stayed throughout the summer. He was fascinated by the change of the vegetation and was happy drawing all day in the fields. He couldn’t get over the beauty of the milkweed with its pods with curious feathers. It took him a long time to get into his drawing. He would sit for quite a while. Then he would get up, move around, take a stick and beat the grass, to be certain there weren’t any snakes in it, and then make himself comfortable. He would have long conversations with the cows too. He said they were very attentive. They used to come to the edge of the fence and he would give them the ‘ladies’ art lectures’ – the same ones that he used to give to the ladies in New York. What was so exciting about it was that he didn’t know what he was doing. He would come back into the house and say: ‘Can you see this?’ I’d say: ‘It’s wonderful, it’s extraordinary.’ ‘Does it look like anything you have seen before?’ He needed constant reassurance that he was communicating, and I would wholeheartedly say: ‘Yes! Yes!’

Cosima Spender

Were the paintings such as One Year The Milkweed and Painting 1944 based on pure observation, or were they also about the memory of his childhood growing up on his father’s farm at Lake Van?

Mougouch Fielding

Gorky’s sight was inventive. His eyes seemed attached to memory – feelings, fear, solid shapes recognised and rediscovered in reality. No observation was “pure”, it was transformed. You know he was not an early talker. His family worried. He called a painting Argula (1938) because he remembered it as the first word he said out loud; it meant nothing. He was too busy seeing, I like to think. Words, explanations and titles did not interest him unless they aroused some remembered feeling.

Cosima Spender

There were some terrible and tough times in his early childhood, and traumatic events that would have made a great impact on him…

Mougouch Fielding

He had been brought up on all these tales about members of his family being slaughtered throughout the generations. It was part of his country’s terrible history. He told me that during the Hamidian Massacres of the Armenian people in 1896, his grandfather had been crucified on the door of his church. His father left the family in 1908 for America and had never sent them any money, so they struggled. He told me the stories about how, as a child, there were times when he would forage for food. In 1918 a second wave of massacres by the Turks started, which forced Gorky to flee Lake Van with his mother and sister Vartoosh. They had to walk all the way to the capital Erevan [Yerevan]. They stayed there for a while and he worked in a carpentry shop making combs. Gorky and Vartoosh were taken to Tiflis [Tblisi], but their mother became so ill from malnutrition that she died.

Cosima Spender

However, there were also good memories of his childhood?

Mougouch Fielding

On the whole, his memories of his father’s family’s farm were happy ones. He always talked about the time before they had to move from the farm. It was the part of his life that he cherished. He told me about the cherry and apricot orchards, climbing trees, looking for birds’ nests and swimming in the salty lake. It was idyllic. He said that there was a storyteller who visited them, recounting tales that had been handed down from father to son. There was a lot of singing and dancing in the village too. Gorky saw himself as part of that tradition. In fact, he recounted how his mother had taken him to a big marble seat in the village and told him that he must be a poet. I think he felt that she had given him a mission.

Cosima Spender

How did he make it to America?

Arshile Gorky

The Artist and His Mother 1926–36

Oil on canvas

152.4 x 127 cm

Courtesy Witney Museum of American Art, New York. Gift of Julien Levy for Maro and Natasha Gorky in memory of their father © 2010 Estate of Arshile Gorky/ ARS, New York and DACS, London

Mougouch Fielding

With the help of devoted American missionaries, they stayed some months in camps in Istanbul before getting passage to the US, changing boats in Patras, Greece.

Cosima Spender

Did he tell you that his name originally wasn’t Gorky?

Mougouch Fielding

No, never. An Armenian grocer on 3rd Avenue and 28th Street told me that he came from this very old family and this place called Lake Van. I told Gorky about it and he was absolutely furious. He didn’t want me to know. I was rightened to death of him in a funny way, and I wanted to take him the way he wanted me to take him. I didn’t think he would keep anything from me. I only knew he didn’t want to talk about it. I knew he was a peasant and came from a place called Armenia, but he never went to the Armenian church and never left me alone for five minutes with another Armenian, including his brother-in-law or his sister. What he liked was a new life in me. I didn’t pry, I wasn’t trying to catch him out. I just took him as he was, so what did it matter if I didn’t know? I don’t know much about my own ancestors actually. He didn’t want me to feel sorry for him; he did not want to be called a refugee ever.

Cosima Spender

How did you meet the poet and founder of Surrealism, André Breton?

Mougouch Fielding

When we came back in the autumn of 1943 from Virginia and Gorky had made all these extraordinary drawings, Matta and David Hare came to see them. Jeanne came to New York and was determined that he meet Breton. She asked Noguchi to arrange a dinner with her, Gorky and me at the Hotel Lafayette (now alas gone). It was a great success. Then Breton came to the studio and was thrilled by the drawings and paintings made in the past two years, and the rest is well known. Breton got Julian Levy enthused. Levy had known Gorky for years but not seen any of his new work. Gorky was to have a show at his gallery in the spring of 1945 with a contract.

Cosima Spender

Did Gorky see himself as a Surrealist?

Mougouch Fielding

He had studied the Surrealists. He knew all about them from exhibitions, their books, poetry and paintings: Dalí, de Chirico, Duchamp, etc. You didn’t have to belong to a club. Surrealism was part of twentieth-century culture. Gorky wanted to be where he was, in America, and his painting to be recognised as American art.

Cosima Spender

How did others view his work at the time?

Mougouch Fielding

When we met, he was viewed as a good painter but unfortunately too much under the influence of Picasso, Léger, etc. But he always had a loyal few who believed in him, his devoted sister for one and later his nephew Karlen (named after Karl Marx and Lenin). I was told he was old hat by an editor of Time magazine. Ethel Schwabacher and Minna Metzger, his students, helped him; Dorothy Miller at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and her husband Holger Cahill were faithful friends who did all they could. But when Breton praised him he was suspected of selling out to fashionable society.

Cosima Spender

As well as Matta, de Kooning was a good friend. What was their relationship like?

Mougouch Fielding

Bill was Gorky’s closest friend and pupil for many years, but he was becoming independent, less under Gorky’s influence. Gorky must have felt this. Matta was a different story – he was Paris, Europe. Gorky listened to him. Matta encouraged him and admired his work; he wanted him to stop practising, to let himself go. Gorky was a master and had nothing more to learn. It took time, but a year or so later, in Virginia, far from New York, he was able at last to do just this!

Cosima Spender

Then came the disasters…

Mougouch Fielding

One upon another. First the studio in Sherman, a very temporary arrangement, caught fire in January 1946. Gorky was dangerously enthusiastic about building fires – he didn’t tell our hostess until it was too late. He just managed to take out a few paintings, his mother’s photograph and a precious book on Ingres. When the fire engines turned up, it was all ashes. I had gone to Washington with the new baby, Natasha, and Maro to see my father and brother, who were back from the wars. I had been there, in the house where I lived as a child, ten days when it happened. I had returned to New York to visit the dentist when Gorky’s voice came over the telephone with the dreadful news. He was coming immediately to 36 Union Square. He sounded dreadfully hollow. It was agony waiting, but when he came, he was as heroic as a phoenix – the paintings were in him. He would paint them again, but where? Our friends were wonderful. Levy postponed the February show to April, Ethel Schwabacher found a ballroom to use for a studio on the seventeenth floor near the Metropolitan Museum. I packed him off early in the morning, took Maro to a nursery school for three hours (she hated every minute she was away), cleaned and shopped and tried to get them to bed when Gorky came back all tired but happy with his work. His pain, however, was not going away, and in late February he went to a doctor he’d seen in earlier years. He never came home. That very day the doctor sent him straight to Mount Sinai Hospital. We had to wait two days for tests. Disaster number two: cancer of the colon. The first days of March. Poor friends: we were helped so much, and how would he, could he, have his show? Well, it did happen and Gorky had his first good reviews. Levy was pleased, Jeanne was not there but bought a painting anyhow, several sales, thank heaven.

We had to get him well enough to stand at his easel. I had to find ways for him to be alone, with the children away from the studio, and lots of fresh air for me. My mother was heroic. She took her grandchildren to the farm with a nanny and eventually Gorky and I followed. We had the farm to ourselves. My father loaned me his jeep and went off to fish in Canada. Slowly Gorky felt strong enough to start drawing again. The barn had burned down. We hunted for houses between Lincoln and New York City. Breton went back to Paris to some acclaim. Matta as well. Gorky made lots more drawings that were sent to Levy, and we stayed in Virginia until late November. Levy wanted more paintings and was complaining, while news from France was not brilliant. Calas was curating a show at the Hugo Gallery and wanted a Gorky. Somehow we got through the winter. I realised I had to get out of his way: he had to paint in his studio. I could take the children to spend the summer in Maine with my great aunt, a student of Dr Jung, a wise old lady and brave enough to have me and the children. We left at the end of May by train – a long trip.

Gorky could have the summer in New York to be free to paint all day and night. Jeanne had moved to New York at last. His friends would be there to look after him. He was happy to know we were taken care of and could lose himself in his work, his only happiness. I left a stack of penny postcards addressed to me in Maine. He filled them out religiously. The summer of 1947 was the most productive period of his life. He made his triumph and we came back in September. He had produced so many wonderful paintings I was dazed. I found a small studio across the street and we tried to work there, but he missed his studio. Where could we, me and the children, go? The Glass House in Connecticut was ready, so we moved there. He hated it and we were looking at other houses. I tried to get more money from Levy. But he just wanted more paintings and Gorky couldn’t have worked harder. It was a terrible life and especially difficult for the children, and it’s too painful to remember… [Gorky committed suicide on 21 July 1948.]

Cosima Spender

Which period of his painting do you think he was most satisfied with?

Mougouch Fielding

Well, it is difficult to say. I remember that when he was showing some of his work at MoMA, one piece was hung next to a Matisse, Gorky having claimed he made it in 1906. He was so pleased that we went back about five times to stand in front of his wonderful painting and look at the Matisse hanging beside it.

Cosima Spender

Why do you think he had to invent so many stories about himself?

Mougouch Fielding

He had built this edifice around himself and his identity. What was the point of telling people about a place they had no idea existed? But by the end the guard that he had erected to protect himself had been broken down, for various reasons, including the bad luck of his operation for cancer, a car accident and his father dying – something he couldn’t tell me about because he had always claimed his father had disappeared when he was a child.

Cosima Spender

And how do you remember him?

Mougouch Fielding

I remember this very proud, amazing person who brought a new dimension into my life that I yearned for. He made me feel alive. That’s what I loved. I know he loved me, just like I know I loved him.