Michael Rakowitz on William Coldstream’s OrangeTree 1 1974–5

Orange. I am in Lisbon in 2007, sitting next to the water at the port. My friend Suhail, a Syrian dentist in New York City and an excellent writer, sends me a text message, asking me to have an orange for him. In Arabic, the word for sweet orange is burtuqal, he explains, because they were commonly imported from Portugal. A thing that is a country that is a colour.

Sir William Coldstream

Orange Tree I detail 1974–5

Oil on canvas

91 x 71 cm

Photo: Tate © The Estate of Sir William Coldstream

Orange. I find myself compelled by moments that occur in everyday life and are not intended to exist as poetry or art, but accidentally become such. As with Natalia Dmytruk, the former sign-language interpreter for UT1, Ukraine’s state television channel. In November 2004, during the Orange Revolution – named for the colour of the popular opposition – she was told to interpret the false announcement that Viktor Yanukovych was the winner of the widely contested presidential election. Instead, she showed up to work, tied an orange scarf to the middle of her sleeve which was revealed every time she gestured with her hands, and deviated from the script of the live televised broadcast. A flash of orange. “I am addressing everybody who is deaf in the Ukraine. Our president is Viktor Yushchenko.” Another flash of orange. “I am very ashamed to translate such lies to you. Goodbye, you will probably never see me again.”

The ones to hear the truth first were those who could not hear.

Orange Tree I was purchased in 1991.

Mark Haddon on Jean Dubuffet’s The Busy Life 1953

Jean Dubuffet

The Busy Life (1953)

Tate

It was David Hockney who pointed out that paintings, unlike photographs, always contain time. They’re records of how the painter’s hand moved over days, weeks, months. There’s a sheen to most paintings before the nineteenth century which renders this work invisible. Abstract Expressionist paintings, on the other hand, take it as their main subject. Dubuffet’s The Busy Life sits midway between the two: a joyous, dancing street scene that’s also the story of how it was painted. And he is incredibly generous about sharing that process with us.

Dubuffet often mixed his paints with grit and sand and oil repellents to make a near-sculptural surface. But here it’s pure oil, a jumbled rainbow ground covered with a thick white paste gouged with a palette knife to make the figures so that there’s no distinction between line and colour. It’s painted in the naïve style of all his mature work, which grew out of his fascination with the Outsider Art he collected (he coined the tern Art Brut). There is a cavalier disregard for anatomy, for perspective, for up and down, and it looks superficially like a child’s work, though anyone who’s picked up a paint brush knows how it is difficult to access and organise this seeming simplicity.

You can stand back and look through this painting. Or you can move in close and follow the adventure of Dubuffet’s hand. Listen carefully and you can almost hear his ghost telling you that this is the secret to cheating death. This is how you move people after you’re dead.

The Busy Life was presented by the artist in 1966 and is on display at Tate Modern.

Andy Holden on Stanley Spencer’s The Resurrection, Cookham 1924–7

Sir Stanley Spencer

The Resurrection, Cookham (1924–7)

Tate

My mother’s uncle John grew up and spent much of his life in Cookham. He used to tell stories about Stanley Spencer: a funny man in a floppy hat, who would push his paints around in a pram and sit drawing apparitions in the churchyard. He and his friends would pass the artist on the way home from school each day. They used to call him names, shouting at him over the wall of the churchyard. Sometimes, while Spencer was sitting painting, they would throw stones at him.

Many years later my mother stayed with uncle John in Cookham, and one afternoon he took her to the churchyard to see where his mother was buried. When he died he left my mother some money, which she used to send me to art school.

Stanley Spencer

The Resurrection, Cookham (detail) 1924–7

Oil on canvas

274 x 548 cm

Photo: Tate © The Estate of Stanley Spencer/ DACS, London 2010

The solid, cold grey gravestones in The Resurrection, Cookham remind me of clambering around on tombs in the churchyard near where I grew up. As a teenager I took

painting lessons each Saturday with the vicar. He mostly just left me to sit and paint, listening to the radio, while he worked on a very large copy of Manet’s Olympia in the other room. I was not sure I could choose just one detail from The Resurrection. I searched the foreground for a stone that uncle John might have thrown. In the end I settled on the woman emerging from a tomb on the right, who looks like she is receiving a letter.

The Resurrection, Cookham, was presented by Lord Duveen in 1927.

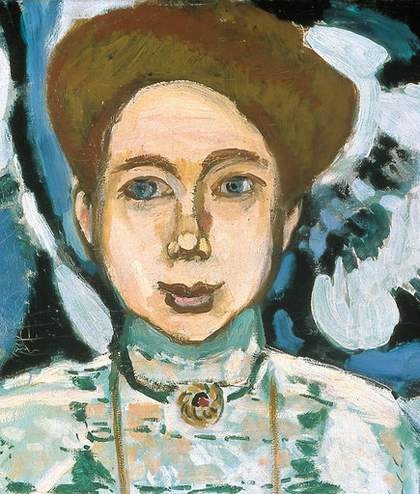

Richard Aldrich on Henri Matisse’s Portrait of Greta Moll 1908

Henri Matisse

Portrait of Greta Moll (detail) 1908

Oil on canvas

93 x 73 cm

© Sucession Henri Matisse and DACS, London 2010. Photo: Tate

I remember I was at a friend’s house, flipping through a book on Matisse portraits. I came to the page that had the image of Greta Moll, which I always liked. Such a funny, cute face with delicate features, and then such a big brutish arm. There was a page or two of text concerning how it came to be, about how she and her brother were patrons, but also took lessons from Matisse. Their exact role was hazy, as they would sit for him, but also he’d teach them about painting. Since they were collectors too, he always gave them rights of first refusal. It was nice to read all this background information. Then a bit later in the evening, my friend wanted to look at the book. She opened the Greta Moll page: “I like this one…” “I do too,” I winked, “I was just looking at it!” So we looked at it again and read the stories. It was more fun to do it this second time.

The first time I really liked Matisse was when I saw the Matisse Picasso show at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. I went with my bandmates, and we saw Matisse’s painting Bathers with a Turtle 1908. It blew me away; it blew us all away. “Where’d that turtle come from?” I hadn’t remembered it with those figures, and I hadn’t really studied Matisse before, so didn’t know there were a few of those figure/dancer on blue and green background paintings.

Years later our band, still obsessed with the turtle, wanted to incorporate one in a sculpture we were working on. For a second we thought about painting it orange, but that obviously would have been a bad idea. As it turns out, the pet turtle industry is a terrible one. They are shipped around over-packed into boxes. Most die and many get sick. So no turtle in our sculpture. Instead, we used dreaming men, which are little clay figurines that we made of a guy doing a back bend.

Portrait of Greta Moll has been on loan from the National Gallery since 1997 and is on display at Tate Modern.