Hornsey College of Art uprising, by David Page

In May 1968 students and a few staff occupied Hornsey College of Art, London.The sit-in led to six weeks of intense debate, extended confrontation with the local authorities and even questions in Parliament. One of the teachers at the time recounts the story

On 28 May 1968, at Hornsey College of Art, what was to have been a one-day teach-in turned into a six-week occupation. There was a parallel occupation at Guildford School of Art, and the action spread rapidly round most of the art and design colleges in England in various forms. It produced two books,* a film, an exhibition at the ICA, newspaper and magazine articles, demonstrations and street events, television interviews, a large number of educational documents containing analysis and proposals for reform, as well as posters, an articulate constituency and (indirectly) the only serious piece of government research into the sector (see The Employment of Art College Leavers: Ritchie, Frost and Dight, HMSO, 1972).

That’s one way of summarising it. In strict dictionary terms it was a revolution – the overthrow of the established government by those who were previously subject to it.

The authorities fled from the main college, which was then run for the duration by students and staff, 24 hours, seven days a week, demanding total commitment. There was a building to run and keep clean, a canteen to staff, food to be purchased, cooked and served, visitors to be monitored and controlled, alongside a system of seminars producing reports to be typed up, reproduced and fed back into the general meetings (and also to the outside audience), where hundreds of students and staff managed to debate and take decisions in an orderly fashion. Because the graphics department was in the hands of the authorities, printed matter had to be produced by available means – mainly linocut – but the rougher images produced seemed to meet the mood of the time, and were consonant with what was being produced via silk-screen in Paris. Some more sophisticated work found its way to printers, such as George Snow’s Snakes & Ladders, and a typographic poster of John Donne’s “No Man is an Iland, entire of it selfe” quotation, which was felt to embody the spirit of the sit-in, featured in a number of London bookshops.

There was much interest from notable people in other cultural areas – indeed, the establishment. William Coldstream, John Summerson and Shirley Williams (at that time Education Minister) treated it with respect, and even some admiration. None of that from the local councillors and aldermen, who had little idea what the institution in their control might be about, but were clear that authority, their authority, was being challenged, and they weren’t having it. Their stance culminated in “The Day of the Dogs”, when a team of security men with Alsatians were sent to surround and seal off the main college building. In the event, students tamed the dogs with biscuits, and the whole episode collapsed into farce. The people who did understand the educational arguments pulled back, saying that, regrettably, there was nothing they could do, thereby leaving the field to Haringey Council, which did not understand, and furthermore did not wish to understand, thank you very much. While this local political battle went on wasting a lot of time and energy, a social and spiritual development occurred alongside. What we aimed to do was simple: as William Blake put it, to build Jerusalem. William Morris, another artist-rebel who started with a concern about furniture and ended up grappling with the whole structure of society, followed a similar path. In 1964, surveying the new DipAD (Diploma in Art and Design), Quentin Bell wrote: “Henceforth it should be possible for a college to develop entirely on its own lines, to follow no matter what eccentric course it pleases, and it does not matter how eccentric that course may be if only the teachers are sufficiently enthusiastic.” (Crisis in the Humanities, edited by JH Plumb, Penguin, 1964.)

We would have said amen to that: what happened was nearly the opposite. The politics of Hornsey emerged from the conflict between Bell’s aspiration and the structures and practices we actually encountered. When eventually an unsatisfactory agreement was brokered between the authorities and the occupiers, the main college was briefly reopened. The authorities’ first act was to tear down everything which pertained to the sit-in: Hornsey posters, French student posters, etc. There’s no vandal like an official vandal. Within a week or two they had also broken all the terms of the agreement. Staff and student sackings and other repressions began. (“No way to run a whelk-stall, let alone an art school” – Lord Longford.) I managed to salvage at least some of the poster lino-blocks before they were destroyed. It was easier to gather documents (which had been sources for The Hornsey Affair): they remained in cardboard boxes through several house moves, and were sorted, years later, by two successive and devoted researchers (the first of whom had to sift out the mouse turds).

What Hornsey meant depended on where you stood, whether you were a teacher or a student, where you were in your life, and so on. This article expresses a partial view by a member of staff, so I asked two friends who were students then to sum up what it meant to them:

As a student on the industrial design course at Hornsey in 1968, I became very strongly aware of the powerful and pragmatic role design could have as an agent for social change and development. The sit-in burst into this environment, and its activities were a natural forum to explore these issues, both through debate and practical projects. Design for learning as a radical process has driven my work since that time.

Prue Bramwell-DaviesThe Hornsey thing was a startling illustration of the potential for a disparate group of people with insignificant initial common cause to develop the ability to discuss and act together in such a way that cohesive and pragmatic philosophical and political expression emerges. That this phenomenon is extraordinary and deeply threatening to institutional establishments is a profound comment on our social organisation and the way in which it continues. It is significant that these were art and design students, doers and makers rather than talkers

David Poston

The Hornsey documents, collected together, now live in the Tate archive, where anyone can read them and may judge whether the schools of art and design are now fulfilling their promise.

* The Hornsey Affair, Students and Staff of Hornsey College of Art, Penguin Education Special, 1969. Hornsey 1968: The Art School Revolution, Lisa Tickner, Frances Lincoln, 2008

The Hornsey files were presented to Tate by David Page in 2008.

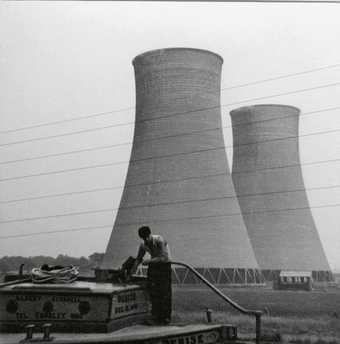

Photograph taken by Prunella Clough of cooling towers, used as source material for her paintings c.1950

© The Estate of Prunella Clough. Prunella Clough Collection, Tate Archive

Prunella Clough, by Margaret Drabble

Prunella Clough’s paintings of slag heaps, industrial buildings and waste ground were based on many black-and-white and colour photographs (one of which is published here for the first time) that she took from the 1950s onwards. She captured a particular post-war sensibility that most ignored, as one admirer of her work explains

The Prunella Clough archive at Tate Britain comprises 22 boxes of very varied contents, including personal and professional correspondence, diaries, notebooks, drafts of poems and folders of artists’ materials – Dutch metal, gold leaf, Dryad paper and a packet labelled REDS, containing pieces of paper and card cut from magazines and packaging, all in different shades of red. It also has boxes of photographs. From very early in her career, Clough took photographs which she used as a record and as source material for her paintings, and was particularly attracted by views of wasteland, by post-industrial scenes, by signal boxes, wires, ropes, fences, walkways, traffic lights, poles and pylons. She was drawn to rubbish and rejects, and to the haunting sadness of the scrapyard. What other eyes do not register she snapped up with her very simple camera, and if you spend a while browsing through her work, it is impossible not to see all around you the neglected corners of our landscape, both rural and urban. She made this territory her own, and opened our eyes to it.

Human figures sometimes appear in her photographs, as they did in much of her early work, where they are always treated with respect, but over them hangs a sense of impending doom. In the 1950s and 1960s the death of large-scale manufacturing in Britain was on its way, as post-war dereliction began to merge with industrial decline. Yet the paintings that arose from these records and reflections often have a transcending light and hope that moves beyond elegy into celebration. It is a mysterious process.

Some of her early black-and-white photographs of harbours, pitheads and slag heaps are tiny, no bigger than a small matchbox or a large postage stamp, but she worked from these to create large oils, such as Tate’s Cooling Tower of 1958, which is confident, luminous and permanent. In later years she took hundreds of Kodacolor shots of highly coloured cheap contemporary objects in street markets and crematoria – piles of plastic buckets, flowers in cellophane, plastic bags, bubblegum dispensers – which found their way into her floating abstracts like airy balloons. Comparing the source photographs (which include an image of a hot air balloon over Wiltshire) with the paintings is a wonderfully illuminating experience, which allows you to be in her company and to follow her journeys, as she transforms the accidental into the enduring.

The Prunella Clough archives were presented to Tate by Anne Robin Banks in 2005.

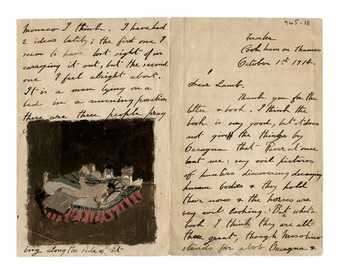

Letter from Stanley Spencer to Henry Lamb, October 1914, including a preparatory sketch of The Centurion's Servant

© The Estate of Stanley Spencer/DACS London 2010. Henry Lamb collection, Tate Archive

;

Stanley Spencer, by Shirin Spencer

The artist’s daughter provides an insight into the background of a letter he sent to Henry Lamb regarding The Centurion’s Servant

“Before the 1914 war I had to be very convinced about a picture before I drew it or painted it. The drawing or painting of the thing was an experiencing of Heaven: it would have been unthinkable that I should or might find hitches or snags.” Stanley wrote this in his introduction to the 1955 retrospective at Tate, where I first saw The Centurion’s Servant or The Bed Picture.

As a small child I often saw the work he was doing in the Sandham Memorial Chapel, Burghclere, but I knew little of his early pictures. In 1935 my Aunty Florence (Stanley’s sister) gave me the book Contemporary British Artists: Stanley Spencer (with an introduction by RH Wilenski) for Christmas. The reproductions were in black and white. I remember being entranced by The Sword of the Lord and of Gideon, though I didn’t understand it. The Bed Picture seemed to me more straightforward – I was happy to think that Christ was going to heal the boy on the bed and that his friends were praying for him. Then I read what Wilenski had written about it, and thought reluctantly the picture was to do with the war. Later, I remember my father saying it was nothing to do with the war and was quite angry that Wilenski should think so. The picture is and isn’t about war – it’s about healing and redemption; but without the war, would it have been painted?

Three of Stanley’s older brothers had joined up at or near the beginning of the war, but Stanley and his younger brother Gil (Gilbert) did not enlist until 1915. In the meantime, they tried to concentrate on their painting and did first aid and drilling in Maidenhead. They were not dare-devils, but they were as ready to go as most of the young men in that village or elsewhere: it was not the pull of Cookham – Stanley would even write “Cookham is sickly” – it was the reluctance of the parents to let their two youngest go. It was not until July 1915 that Stanley wrote in a letter to his friend Henry Lamb: “Now that Mar’s attitude has altered, and has proved that she can do without us without dying as she thought she would, and also Cookham having been completely stripped of its youth, I feel I can no longer stick living here, but must exist somewhere else, suspend myself till after the war…”

The months between the outset of war and July 1915 were probably the most frustrating and distressing of his young life. “The more beastly the stories become, the more I feel I ought to go and do something… Gil walks around like a lump of lead.” His brother Will played Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata. “The slow movement makes me think the world’s nearly coming to an end.” For me, the most poignant of the statements is: “When I feel the horror of war most is when I go to bed.”

When brother Sydney was on leave they would share a bed. He wrote in his diary how Stanley tossed and turned, and it was during those months that Stanley painted The Centurion’s Servant. In a letter to his friends Jacques and Gwen Raverat sent as early as September 1914, he writes as if he had already painted the picture and would like to do another the same size (square) of Christ and the Centurion and let the two pictures appear beside each other with a little space between. He was justifiably proud of his painting. In July 1915, when he was about to join the RAMC, he wrote to his friends again: “My bed picture is an example of how a picture ought to be painted. Everything in that picture, the colour particularly, was perfectly clear, and the way to get the colour decided in my mind before I put the brush to canvas.”

I think that this is a picture of hope. The servant will rise and greet his friends, and Stanley has found an oasis of peace and joy – and the strength to paint a miracle.

The letter to Henry Lamb forms part of the Henry Lamb archive which was purchased by Tate in 1994. The Centurion’s Servant is on display at Tate Modern.

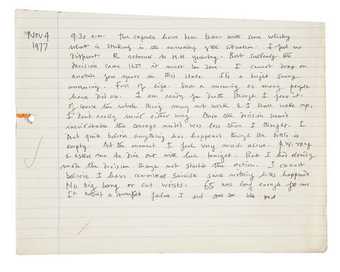

Keith Vaughan, by Veronica Gosling

Keith Vaughan was diagnosed with cancer in 1975 and two years later he committed suicide, recording the last moments of his life in his diary as the drugs overdose took effect. Here, one of his close friends remembers the final hours

For 25 years my husband Bob and I had this old wooden box under our bed. On the lid, in Keith Vaughan’s neat and spidery hand: “This is the only example I have of my father’s writing” followed by a chalked name. Inside were all of Keith’s journals written in foolscap notebooks, including his final entry, 4 November 1977. We had these notebooks because Prunella Clough and I were the ones who, after his death, cleared up his belongings. Bob, Patrick Woodcock and Prunella, long-time friends, were his executors.

Private, unedited journals are not usually read while their author is still alive. To read them, after our long friendship, was for me to understand how little I knew Keith; I just knew that part of him which responded to us, just a particle of the man, what happened to him when he was with us.

For Keith, his journal was as an intimate friend to whom everything had to be said – feelings, acts of all sorts, dreams, and finally these fifteen lines leading up to his oblivion, for which he was eager… though “the whole thing may not work and I shall wake up…” How like Keith! Hedging his bets, ready for the next entry, how it would be to wake up. Good? Bad?

On 5 November, fireworks day, he could have woken up. He didn’t. The day before his death, Keith comes to supper with us at our house in Downshire Hill, Hampstead, as he has so many times before. “Is it just us?” he asks, and from his tone I know he hopes it is. “No, we’ve asked…” But I can’t remember who. I felt his disappointment.

We had supper accompanied by good wine. Towards the end of the meal Keith and Bob talked about the wine, as they had done towards the end of the many meals we had had together over the years, at his studio, at our house, on family holidays in Wales and the Scilly Isles (where his shrimping skills were notorious) and at his cottage in Harrow Hill. After supper we decided to listen to our record of Gerard Hoffnung’s reading of a letter from a bricklayer to his company requesting sick leave – barrel and bricklayer colliding as they go up and down on pulleys. The timing of Hoffnung’s reading is brilliant. We laughed and laughed. Keith cried with laughter, his gesture I can see now, wiping his eyes with the back of his hand.

At the end of the evening I said to Keith: “You look tired, shall I drive you home?” “No, I’d rather walk,” he replied. The following day, his friend John McGuiness phones us early afternoon and asks us to come over to Belsize Park; he thinks Keith is dead. Keith is sitting slumped over his table in the studio, carefully dressed, and wearing a brown jacket, soft material. His pen is still in his hand. On this page, this last entry, you can see it here, as we did, Bob and I, and also on the table is an empty glass and an empty pill bottle.

Sometime before this we had had a conversation about how we might want to die. Keith said he would like to have a party with all his friends around and he would be lying on his sofa and he would die, and everybody would be having a good time and nobody would notice.

Keith Vaughan’s diary was acquired by Tate in 2008.

The final entry in Keith Vaughan's diary, dated 4 November 1977

© Veronica Gosling. Keith Vaughan collection, Tate Archive

John Banting, by Louisa Buck

In 1930 John Banting produced a handmade bound volume which he filled with a witty, satirical portfolio of the art world. Titled For Social Service, it is as acerbic a portrait of a society as any you might find today. The original cataloguer of the Banting archive celebrates its enduring appeal

A page entitled Art Sharks from John Banting's acerbic social satire For Social Service

© John Banting, John Banting collection, Tate Archive

I first saw the paintings and prints of John Banting more than 25 years ago in a small gallery in the New Kings Road, and I was immediately struck by the inventive elegance with which they conjured up bizarre hybrids of organic forms and human body parts, all lashed together with a fluid Cocteau-esque line. Especially appealing was a portfolio of blueprints made during the 1930s (later published in 1946 as A Blue Book of Conversation), which ruthlessly satirised the pre-war social scene by creating a grotesquely surreal cast of semi-human confections fashioned out of bones, entrails and insect bodies, who spouted tirades of nonsensical small talk and answered to such deliciously absurd names as Mrs Fuschia Stingwing, Colonel Molars and the Dorsal Twins. More than 70 years later, Banting’s monstrosities are still wickedly recognisable: I rather fear I could easily be one of the cackling bone-headed crew depicted in Art Sharks sipping cooking sherry.

A cheekily handsome, gay working-class south Londoner, in his heyday Banting was a conspicuous presence at the plethora of pre-war parties and pranks where the Bright Young Things merged with Bloomsbury. He painted murals in Rosamond Lehmann’s hall, designed book jackets for Leonard Woolf ’s Hogarth Press and exhibited regularly with the British Surrealists. At the same time he was also mixing in avant-garde circles in Paris – Marcel Duchamp’s partner Mary Reynolds was a lifelong friend – and other boon companions included the doomed socialite Brian Howard, the nonconformist artist Edward Burra and the maverick publisher Nancy Cunard, with whom he visited Harlem and Spain during the civil war. Yet while Banting was frequently in the thick of things, he always felt he was an outsider, and – as this book confirms – was quite prepared to bite the hands that patronised him.

Sadly, this energetic maverick never fulfilled his early promise: as his drinking escalated, his work became increasingly uneven and repetitive, and he died in obscurity in Hastings in 1971. I never met John Banting, but I owe him a great debt, as it was while I was investigating his life and work that I met and befriended his executor George Melly, another nonconformist hedonist with a keenly subversive streak.

For Social Service was acquired by Tate in 1977.

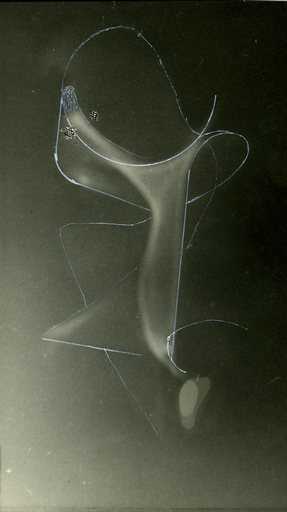

Experimental photograph by Naum Gabo, taken on 16 October 1941

© Nina Williams. Naum Gabo collection, Tate Archive

;

Naum Gabo, by Nina Williams

The Russian-born sculptor who became a leading exponent of Constructivism is well-known for his three-dimensional works, but, as his daughter reveals, he also took enigmatic and beautiful photographs, one of which is published here for the first time

Gabo wasn’t much of a photographer. He had a stereo camera that he couldn’t use very well, and his stepsons, who were good photographers, took the 3D slides that are in the Tate archive. He delighted in a little Minox camera, a “spy” camera. The moment he pressed the shutter he always said “Hopla!” and the whole camera twitched upwards. That makes these photographs even more special, because Gabo succeeded in taking them. He saw the changing reflections made by the sun on the toaster near the picture window in his house, and managed to capture them on film. He was always passionate about light and space.

One of these photographs is reminiscent of his work, but whether a sculpture grew out of this, or he saw a resemblance to his work in the reflection, I have no idea. On some photographs he has highlighted parts of the image, and this may be an indication of a sculptural idea.

The photographs, as well as models for works, writings and love letters, were presented to Tate by Nina and Graham Williams in 2007. Construction in Space with Crystalline Centre 1938 –40 and Head No. 2 1916, enlarged version 1964, are on view at Tate Liverpool.