Whether Theo van Doesburg would have become the international pioneer of the De Stijl movement without his personal confrontation with the First World War remains unknown. Although the effect of the war on the visual arts in the neutral Netherlands still remains underexamined, it had a particular influence on van Doesburg. Before the conflict he was married and lived and worked as a self-taught artist without any international experience in Amsterdam, where he made paintings in an accepted ‘brown’ realistic style: labourers and self-portraits and drawings of people in the city. In his artistic examinations he aimed for a humanistic, utopian and socialist edification of artist and spectator. But during the war he began an extramarital relationship and started to experiment in an abstract style. Afterwards, he occupied himself as an avant-gardist roaming around Europe, totally devoting himself to promoting modern art.

In August 1914 he was stationed, as a conscripted sergeant, in the region of Tilburg in the south of the Netherlands, not far from the Belgian border. Even though his home country remained neutral, the war was very close by, and each day a procession of Belgian refugees passed through. Such confrontations rocked the foundations of van Doesburg’s Tolstoyan belief in a spiritual evolution of humanity, and he realised that he had been unbelievably naïve. He believed that to realise truly modern art, the artist needed to assume a radical position. First and foremost, he or she had a duty to serve art and only then the public. After his demobilisation in February 1916, he reorganised his artistic practice along the lines of his new-found progressive ideas, orientating his painting to the abstract art of Kandinsky. He also saw the Cubism of Picasso and Severini as contributing to the new art. However, the war made it impossible to have a direct exchange with these artists, so he was forced to find colleagues within the borders of his own country.

He discovered the first of these in 1916: Piet Mondrian and Vilmos Huszàr. In both he recognised not only kindred spirits, but also artists who were well-informed on international developments. Later that year he met Bart van der Leck, the idiosyncratic painter who strove for the fusion of painting and architecture, and the young architect J.J.P. Oud, who pursued the same goal, but from the position of architecture. During the war years, these artists not only strengthened van Doesburg’s ideas, but also influenced them considerably.

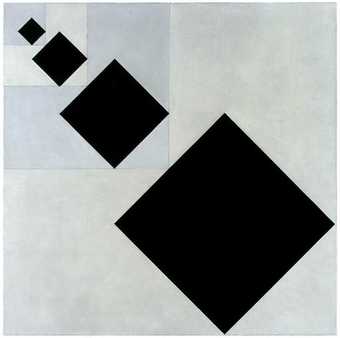

Theo van Doesburg

Arithmetic Composition 1929–30

Oil on canvas

101 x 101 cm

Courtesy Kunstmuseum Winterthur

In 1916 van Doesburg set up various art societies in order to propagate his ideal of realising a new abstract art in a modern environment. Even the first exhibitions, however, demonstrated the underlying differences between the members, so he decided to give priority to the establishing of a magazine. This would provide a platform for a loose-knit group of artists with a common vision. It was a great success. With the help of Mondrian, Huszàr, Van der Leck and Oud, his friend Antony Kok and his second wife Lena Milius, van Doesburg worked hard to produce the first issue of De Stijl, which appeared in October 1917. Alongside contributions from his Dutch collaborators, the first volume included images by international artists: Severini, Archipenko, Kandinsky and Picasso. The magazine was rapidly distributed abroad and appeared until van Doesburg’s death in 1931. Oud involved van Doesburg in his architectural projects as quickly as possible. One of their first collaborations resulted in the Vakantiehuis De Vonk, the holiday house for factory girls completed in 1918. For the façade, the artist created glazed mosaics and chose the colours for the windows, doors and shutters: yellow, green and blue in combination with black and white. In the interior, they made something entirely new. Oud placed a free-standing staircase with open sides in the middle of the hall, around which van Doesburg painted the doors in contrasting colours and laid a tile floor with an ingenious pattern that turned the space into a dynamic art experience. In these early years, he also worked with Jan Wils, another architect who made several contributions to De Stijl. He designed furniture and colour schemes for a café-restaurant by Wils and van Doesburg’s stained glass windows were incorporated into a house designed by the architect, the interior of which the painter decorated from top to bottom in the colours purple, green, orange, blue, black and white.

After the war ended Mondrian moved back to his studio in Paris. In the early months of 1920, van Doesburg stayed with him for two weeks and got to know Léger, Archipenko and other Cubists. He also encountered work and literature by the Dadaists, whom he admired, but for the moment he kept his interest in these two contradicting movements separate and focused on the work of the Cubists and Neo-Cubists. Their art complemented that of the proponents of De Stijl and, furthermore, they were well organised with their Section d’Or, the society for which he arranged an exhibition in the Netherlands in 1920. Reciprocal efforts followed. Thus, in the winter of 1920–1 he was invited to participate with his De Stijl group in an international exhibition of modern art in Geneva. The influence of Dada was noticeable in the group manifesto and in his poem X-beeleden (X-images), which he published in De Stijl in 1920 under the pseudonym I.K. Bonset. Personal contact with the Parisian Dadaists came later.

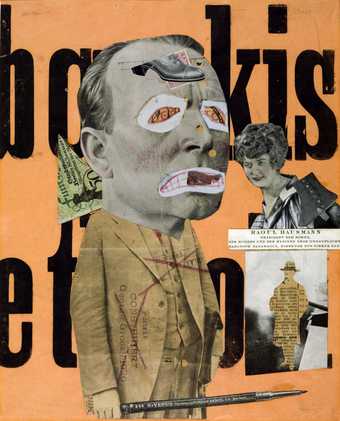

In early 1921 van Doesburg began a European trip with Nelly van Moorsel, who became his third wife. He established himself in Weimar, near the Bauhaus, until the end of 1922, anticipating that this most modern of academies would be the ideal place to develop his De Stijl aspirations. But the training bitterly disappointed him. It was old-fashioned and unprogressive. He made no attempt to hide his criticism, so an appointment as a lecturer – where his true ambitions lay – was simply not possible. So he set up his De Stijl course at home, with many students and lecturers from the Bauhaus taking part. He travelled regularly from Weimar to Berlin. The lively atmosphere of the city inspired him. In his poetry this led to his Letterklankbeelden (Letter Sound Images) in 1922. In Berlin he sought out the international community of Cubists, Constructivists and Dadaists and befriended the Russian Constructivist El Lissitzky. At the end of May 1922 he, Lissitzky, the like-minded Berlin Constructivist Hans Richter and Dadaist Raoul Hausmann attended a congress in Düsseldorf that was intended to establish a sort of internationale of the avant-garde. They rejected the set-up, which they found too bureaucratic, and left the gathering under loud protest. Van Doesburg proceeded to devote an issue of De Stijl to their views. That summer he and Lissitzky worked together on the latter’s original Russian story About Two Squares so that it could appear as a special issue of De Stijl. Afterwards, he contributed to Lissitzky’s magazine Veshch, just as he did to the journal set up by Hans Richter. Two years later he designed a layout for a book with Kurt Schwitters and Käthe Steinitz: Die Scheuche (The Scarecrow). He was also closely associated with the Hungarian Constructivists László Moholy-Nagy and Lajos Kassàk, who were connected with the magazine MA (Today) that was published from Vienna and Berlin, and exchanged articles and photos with them. In fact, Kassàk had already been influenced by De Stijl – in 1920 his production of the cover of MA was inspired by the new look of De Stijl, which van Doesburg and Mondrian had designed shortly before.

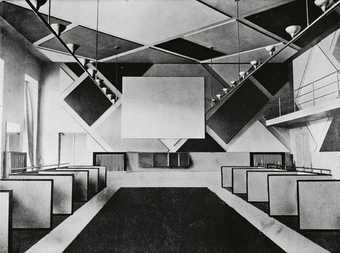

The cinema and ballroom of the Cafe Aubette designed by Theo van Doesburg, photographed in 1928

Courtesy Musées de Strasbourg

Van Doesburg resumed his contact with the Paris-based Dadaists Tristan Tzara and Francis Picabia in Weimar. With their collaboration he realised his plan to publish the Dadaist Mécano in addition to De Stijl. For this he approached Hans Arp. Four issues of Mécano appeared between 1922 and 1924. In this ‘entirely foldable magazine’, drawings were placed beside French and German poetry and prose, something that was particularly sensitive because of the political conflicts over the Ruhr region – and exactly why van Doesburg found it a wonderful challenge.

In 1923 he also gave the Netherlands an opportunity to see his Dada side. Following on from the Dada soirées in Germany, he had a troupe of six artists in mind, including Hausmann and Tzara. Ultimately, the co-operation was limited to Schwitters, Huszàr and Nelly. In variable configurations they undertook twenty appearances in three months that ensured the necessary upheaval in the Netherlands. Van Doesburg read seriously from his pamphlet What is Dada?, Schwitters recited poems and made strange noises, Nelly played the piano and Huszàr intermittently let his mechanical moving figures cast shadows on a white backdrop. The Dada campaign more or less concluded van Doesburg’s German period. Paris replaced Weimar as the epicentre. There, in the summer of 1923, he began preparations with the young Dutch architect Cornelis van Eesteren for the exhibition promised to him by the gallerist Léonce Rosenberg, who was particularly keen on the collaboration between the De Stijl architects and painters. However, Oud had broken with the movement at the end of 1921 and Wils remained excommunicated as a result, all of which left an architectural void. Fortunately, in the meantime van Doesburg had recognised the qualities of the furniture designer Gerrit Rietveld, who had designed his chairs on De Stijl principles since 1919. He had also started to value van Eesteren, but neither yet had their name to any (completed) De Stijl architecture by 1923. None the less, van Doesburg succeeded in involving them in the exhibition preparations. Most specifically through an intensive collaboration with van Eesteren, he realised different maquettes for astoundingly progressive architectural designs, such as those for their Maison particulière and Maison d’artiste. He also succeded in showing the work of Oud and other De Stijl architects in the exhibition, if only in the form of drawings and photographs. Although the show was a highpoint in the history of the De Stijl movement, it failed to attract any commissions. So in the following years van Doesburg once again concentrated on his painting. His Contra-compositions are particularly good examples of how he was able to incorporate the achievements of his architectural models into this new transverse painting style.

When he was invited by Hans and Sophie Arp in 1926 to work with them on the creation of a large entertainment complex in the famous l’Aubette building in Strasbourg, van Doesburg grabbed the opportunity with enthusiasm. In this project he saw the possibilities of realising an even greater synthesis between painting and architecture. For almost two years he worked on the diagonal colour designs for the large hall where dances could be alternated with film screenings. He experimented with new materials such as rubber and aluminium in the banqueting hall and determined the design of everything from the ashtrays and crockery to the signage. But when it was completed in February 1928, the public did not take to it – to the point that the interior was modified within weeks.

Staircase at the Cafe de Aubette designed by Theo van Doesburg and Sophie and Hans Arp, photographed in 1928

Courtesy Musées de Strasbourg

That the ideals of De Stijl in the modern context and on this scale were not appreciated deeply affected van Doesburg. He reacted as he always did: with a radicalisation of his ideas. His art would need to become more rational, colder and harder. Moreover, he devised a systematic approach that was founded on a spiritual basis. In his paintings he deployed a mathematical model that dictated the size and proportions of the colour fields. He also designed a house incorporating a studio for himself in Meudon, near Paris. But he never saw the project realised. He was increasingly debilitated by asthma and bronchitis which prevented him from working much after 1930. Van Doesburg did not personally participate in the last collaborative project of De Stijl. After a year of illness, he died on 7 March 1931 in a health clinic in Davos. Nelly and Lena subsequently decided, together with Arp, to produce one more issue of De Stijl, devoted entirely to him. Nearly everyone co-operated and thus, one year after his death, the last issue of De Stijl, the van Doesburg issue, appeared.