Since the early 1960s, when the American version of Pop Art seemed to extinguish the spiritual and existential ambitions of Abstract Expressionism, an assumption was quickly made that this new art was the triumph of a fully ascendant materialist America. Indeed, the British art of the Independent Group that preceded American Pop was far more equivocal, if not occasionally caustic, about this materialist sublime. That made perfect sense. This British art fixed its gaze on a society that had suffered greater material deprivation than America knew during and after the Second World War. In that fantastic time capsule of London’s art scene of the 1960s, Bryan Robertson, John Russell and Lord Snowdon’s brilliant Private View, published in 1965, there is the threadbare milieu of thin wool jumpers in chilly rooms, of art schools in which all the strategies of making do and getting by were played out against a sense of hope rising through the meagerness of life (and particularly art life) in the metropolis.

Gerhard Richter

Party 1963

Oil on canvas

150 x 182 cm

Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © Gerhard Richter

But the immense swell of economic change in the half century since has inevitably altered our understanding of what Pop signifies – not simply in the history of material culture, but in the broader, deeper sense of a symbolic, socio-economic representation of what it was to be a social subject of commerce; to be objectified as an instrument of a present uprooted from the obligations of tradition and compelled by new laws of a dazzling material subjugation.

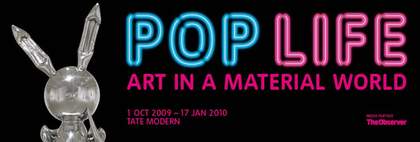

Of course, Tate Modern’s Pop Life: Art in the Material World propels itself from capitalism’s post-war euphoric rise and its impact on the formation of artists in the wake of Andy Warhol’s continual spinning of flesh, money, celebrity and death in the centrifuge of his obsessively entrepreneurial imagination. The idea of the artist as a self-determined subject whose identity distributes itself across all forms of media and capitalist production is a potent, sometimes celebratory and sometimes cautionary tale. Each and all of these characteristics shine luridly in the work of those post-Warholian artists that populate the show at hand. But theirs is only one narrative of the impact of Pop, whether American, British, or – just as riveting – the case of Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke’s phase of Capitalist Realism in Germany.

There is another narrative that lies like a genetic tributary off the mainland of Pop, and that is the art of the social. I mean the art of the 1990s and after that replaces the art object and the artist as a brand (a separate but related object) with social interaction as the work itself and the artist as its facilitator. I’m talking about such artists as Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Liam Gillick, Philippe Parreno, Rirkrit Tiravanija, but also a far less acknowledged group including Lee Mingwei and Robin Winters to Christine Hill, and younger artists such as Ana Prvacki, Bert Rodriguez and Eduardo Sarabia. Each of them defines their art in relation to the notion of a society of individuals joined together in some practice of communal order.

And each of them asks two fundamental questions. First: what is the nature of this communal order? And second: how can we coincide as subjects in a state of consensual, productive life? Or simply: how do we live together? The way from Warhol to our contemporary art of the social passes through the democratic field of Joseph Beuys, whose spiritual ambitions and vision of a global creative commune would seem at odds with Pop, but redounds to a similar morphology of communal belonging. Both the Pop artists and Beuys held up a mirror to the new idea of a mass society, whose consequences of life were founded in a consumerist culture that left behind the memory of its past like the faded tail of a comet. It left the past behind eagerly, enthusiastically, relentlessly. The Pop artists endorsed this capitalist-induced oblivion cheerfully on the whole, while Beuys’s messianic mission was to incur a remembrance of Germany’s terrible history at the same time that he brought a compensatory healing through the forward-looking emancipation of creative citizens and their union in a new creative state.

Rirkrit Riravanija

Untitled (the future will be chrome) 2008

Mirror polished stainless steel and glass ping pong table

22.9 x 12.7 x 76.2 cm

Photo: Douglas Ljungkvist © Rirkrit Tiravanija.

Whichever life-sphere attracts you, the fact of a large communal life is central – this embracing mirror of the mass is the triumph of the Pop artists and Beuys alike. But there is a crucial difference, which separates Pop and post-Pop from Beuys and the artists of the social. I think of this difference first in terms of the fetishised nature of the Pop object: the thing itself and the accumulation of things that have an almost erotic charge, while the art of the social is focused on the environment of interaction in which the subaltern of commerce becomes implicitly a liberator through the assertion of communal agency. At the base of this difference is Pop’s intrinsic endorsement of bureaucratic culture, a culture driven by the machinery of a monolithic post-war industrial complex. Warhol indulged in a dizzying enchainment to hierarchy from the beau monde to the demi-monde. In fact, all of the Pop artists, even Claes Oldenburg, assumed a capitalist plutocracy that, whether celebrated or criticised, remained a given of social order. You can say the same of the post-Pop trio Koons-Hirst-Murakami. This is directly antithetical to the art of the social, which invokes in its notion of a Beuysian creative democracy the inquisition, disruption and levelling of the bureaucratic, of the rigidifying formations of capital.

And so I offer to you an imagined exhibition down another corridor in the museum. Not to say that I deny the power of these luxe objects or the cool indulgences of materialist, self-packaged identity on view in Pop Art: Life in the Material World. But this other path presents a different view of the triumph of Pop, one that is less emptying in its construction of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century self; one that offers other models of formation not only of the self, but of the network of selves we call society.