John Coplans

Detail of Self-Portrait (Torso, Front) 1984

Photograph on paper

115.6 x 81.7 cm

Photo: Tate © The Estate of John Coplans

Tim Etchells on John Coplans’s Self-Portrait (Torso, Front) 1984

It’s the texture of the skin that summons a number of things. Memory of my grandfather, hooked up to an oxygen cylinder in the front room of the prefab bungalow, Alvaston, near Derby, 1980-something. His hands. Neck. Face. My brother’s hands too, which I always think look older than mine, even though he’s younger. But he’s worked outdoors most of this past twenty years and his hands have lived a different life from mine. Marked. Weathered, where mine stayed pretty much soft – computer keyboard fingers. Despite that, looking at this detail it’s also my own skin that I think of. The realisation I had at age 21 that this skin is not invulnerable – that it can be damaged, changed, altered forever. That was a hospital experience – the skin cut deep then sewn, resulting in a neat scar at the shoulder, albeit some not so neat marks in my mind. And since then, flooding in by association, come a lot of other hospital times, hospital thoughts and surgery scars. That’s not what’s there in the Coplans, of course, but what I get from his looking at his own skin like this, is that confrontation with your own decay, with the body doomed as well as beautiful, with the fact of my own body as a time-marked, changing one. I was at the pool some weeks ago, swimming. Two kids swam by as I stood in the shallow water, and I watched one of them clock the scar down the centre of my chest. I’m thinking of the things that happen to the body, things that can’t be undone.

Self-Portrait (Torso, Front) was presented by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery, courtesy of Marsha Plotnitsky, in 2000 and is on display as part of ‘Performing Sculpture’ at Tate Liverpool.

John Coplans

Detail of Self-Portrait (Torso, Front) 1984

Photograph on paper

115.6 x 81.7 cm

Photo: Tate © The Estate of John Coplans

Sally O’Reilly on John Coplans’s Self-Portrait (Torso, Front), 1984

There is a curious transitional part of the male anatomy that fascinated me as a child. No, it’s not the perineum, which I liken to the week between Christmas and New Year. Neither is it the hairy swatch between the knuckle and first finger hinge. It is the gully where the leg meets the belly, just above the hipbone, which looks for all the world as if it facilitates an oblique twist that brings the leg sticking out at a sick angle with the foot way up above the head. I had forgotten about this fascination until recent research led me to John Coplans’s photograph, where this gully becomes the jowls of a softly mobile, distinctly irritable face. I had forgotten because I had, until recently, maintained an appreciation of bodies that was, while not unsensual, less visually orientated than it might be. Practising amateur psychology on myself, I would say this was to suppress the fact that I was raised by naturists. My stepfather could regularly be found of an evening, stainless steel pint pot full of home brew in hand, displaying his ruddy undercarriage against the dark green living room carpet, like a painter’s exercise in complementary colours. As a consequence of many hours hot and cross in saunas, or bored and confused on nudist beaches, I had put the adult male body to the bottom of the must-see list. On reflection, though, I think this is a real shame and I fully intend to readdress it.

Eduardo Paolozzi

History of Nothing 1963

Film still

Courtesy British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection © The Estate of Eduardo Paolozzi and DACS, London 2009

Mark Leckey on Eduardo Paolozzi’s History of Nothing 1963

In Eduardo Paolozzi’s collaged film History of Nothing, industrial machinery intrudes into Victorian parlours, manifesting itself

amid the chintz and well-turned table legs of the drawing room. The Victorian man has brought his steam engine home to play with, his “mechanical bride” and his “bachelor machine”. Now he has the device to enact his most cherished classical myth – of Pygmalion and his Galatea – where the alluring cold perfection of the sculptor’s statue is brought to life to animate the gentleman’s desires. I believe that we – here and now – inhabit a fantasy that was dreamt up by that most inventive and productive era. The Victorians imagined a world of “pictures-on-air” transmitted instantly through the ether; of machines that would allow us to make visible the apparitions of our imagination, a fevered dream induced by the dual forces of technology and spiritualism.

Paolozzi’s History of Nothing was made in 1962, so sits roughly equidistant between that age and our time. (It’s also about when I was made.) He understands that the technology that was set in perpetual motion is in a process of transforming us into beings disincorporated from our bodies. The film produces in me a similar anxiety, that if, like in a J G Ballard short story, a young Paolozzi from 1963 encountered us today, he would recoil at how far our mechanomorphism has progressed.

History of Nothing is on view at Tate Modern.

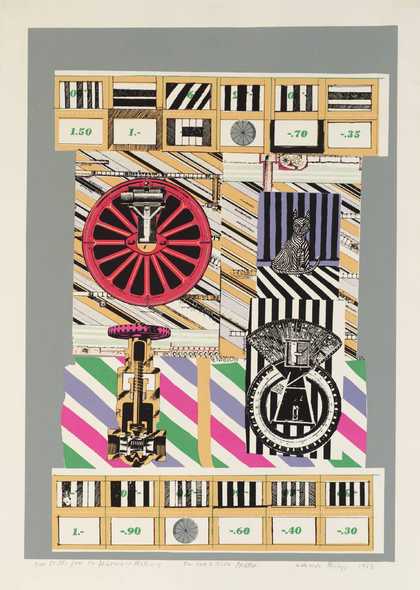

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi

Four Stills from the History of Nothing (1962)

Tate

Martin Bax on Eduardo Paolozzi’s Four Stills from the History of Nothing 1962

Weird things appear in Eduardo Paolozzi’s collages, prints and film. Where, you might ask, did the cogs come from? Paolozzi contributed to twenty numbers of Ambit magazine over a more than 30-year period. Images by him first appeared in Ambit 33 in 1967. Some early ones came from the boxes of silkscreens he was generating at the time. These are extraordinary objects.

After a time I would ring him and suggest we have more of his work for the magazine. He would offer me a bunch of images to select from. When I brought the batch back after publication, he would sign one or two of them and throw them back at me as a gift. A visit to Eduardo’s studio was always fascinating. He was producing artefacts that were to “go out”, but at the same time he was always collecting new material which he saw himself using. He stood above a bin and tore pictures out of what he was studying. These became part of his image bank, stored and filed around his studio. He would open a drawer and pull out what he wanted. On one occasion he opened a drawer full of playing cards – passing me the most obscene pack to look at, while he considered the images on one he had bought in Iceland of Nordic heroes. But no, he didn’t want that today, and he was on to something else from his store, continuously observing and re-creating our visual world.

Four Stills from the History of Nothing was presented by Rose and Chris Prater through the Institute of Contemporary Prints in 1975.