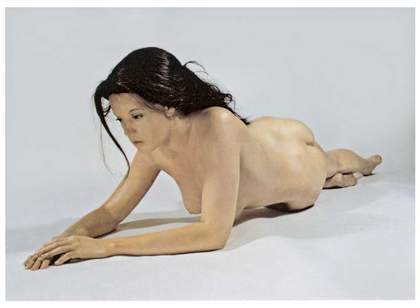

John De Andrea

Reclining Woman #1

Oil and resin

Dimensions variable

Collection Mr & Mrs David W. Bermant

Courtesy Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art © John De Andrea

In 2000 the Grand Palais in Paris put on the exhibition Vision du futur with secular and religious visions of the future from Babylon to now. This foray into cultural history was richly illustrated with fine objects and magnificantly presented. However, when visitors stepped through curtains into the final room, they found themselves in a dimly-lit space filled with plastic buckets, tin tubs and plastic sheeting, like a giant broom cupboard. Water was dripping from the ceiling into numerous judiciously placed containers. Taken aback and disorientated, they picked their way through the room, its walls adorned with large-format oil paintings in the Soviet Realist style, lit by cheap spotlights – a shabby-looking, dust-ridden display that had nothing in common with the aesthetic of the splendid rooms they had just passed through. It is, of course, sometimes the case that an exhibition proceeds from initial pomp and ceremony to a more sobering close. But there was something amiss here, and gradually it came to this particular visitor, still all alone in the room, but now starting to smile – “It’s art, it’s an installation, it’s a piece by Ilya Kabakov!” With some relief, much happier and even a little proud of himself, he now walked round taking in every detail, much impressed by the perfection of this imitative scenario, with its paintings specially made by Kabakov and a sophisticated sound-collage by Vladimir Tarasov.

Maurizio Cattelan

Andreas and Mattia outside Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea 1996

Installation view

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © Maurizio Cattelan

Ilya Kabakov

Incident at the Museum or Water Music 1992

Installation view at Ronald Feldman Gallery

Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, New York © Ilya Kabakov

Kabakov’s installation, Incident at the Museum or Water Music, was first shown at Ronald Feldman Fine Art in New York in 1992. It describes the misery of the art business in provincial Russia and the related remised of a political utopia. The Paris show could hardly have come to a more fitting close. On his perusal of the room this visitor registered something of the failure of a vision, something of the precarious situation of the museum as an institution and of the capacity of art to give form to intellectual insights.

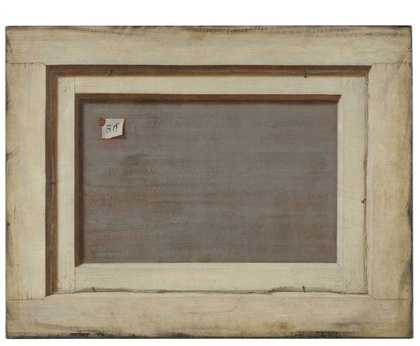

Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts

Trompe l’œil. The Reverse of a Framed Painting 1670

Oil on canvas

66.4 x 87 cm

Courtesy Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

The central music ploy was to create an all-embracing, immersive deception. Kabakov has himself described this as “total installation”. For the exhibition-goer, finding himself in the completely convincing illusion of the gallery space was like stepping into the wrong film, and he was forced to re-orientate himself. In that brief moment of uncertainty, as the brain was urgently casting around for some explanation, it bounded in seven-league boots through the history of art and the various station of trompe l’œil since antiquity - and was astonished to find that the Parrhasius effect still works today. It was in 5BC that Parrhasius won the competition with his fellow painter Zeuxis to see who could create the most naturalistic illusion: like his rival, Parrhasius was able to deceive the birds into pecking at the grapes in one of his paintings, but he also fooled Zeuxis about the very existence of a painting. He succeeded in portraying a curtain so realistically that Zeuxis tried to push it to one side. Even the connoisseur had been duped, and had to admit defeat.

It may seem remarkable that mimetic deception and illusionism still feature in the repertoire of artists today. One might be forgiven for imagining that trompe l’œil lingers on on in in advertising, wax figures or popular cinema (Woody Allen, The Purple Rose of Cairo, 1985). Far from it. Visual artists still continue to use it in an age after Duchamp (and his strategy of disillusionment), even if no longer predominantly in painting, with its classical roots, but rather in sculpture, installations and – interestingly – in sculpture-based photography.

Celebrated as the art of illusion in antiquity, trompe l’œil painting was at its height in the early modern era. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries artists such as Juan Sánchez Cotán in Spain, Samuel Hoogstraten in Holland and Cornelius Gijsbrechts in Denmark created virtu-osically naturalistic still lifes with fruits or sundry items. The objects in their paintings were usually life size and the intention was that the high level of realism should outwit the eye as a critical organ. Things seemed entirely within reach, yet any attempt to grasp hold of them was in vain. Gijsbrechts’s acclaimed painting of the back of a painting references the theoretical aspects of this strategy of mimetic reproduction. Like the Beligian Surrealist René Magritte – albeit 300 years earlier – he used painting to address the iconic status of the picture as such by showing that, to the viewer’s surprise and delight, paintings can reflect both on themselves and on their relationship to the viewer.

Juan Sánchez Cotán

Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber c.1602

Oil on canvas

69 x 84.5 cm

Courtesy San Diego Museum of Art, gift of Anne R. and Amy Putnam

Samuel van Hoogstraten

Trompe l'œil 1666–78

Oil on canvas

63 x 79 cm

Courtesy Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe

Ever since then, the practice of trompe l’œil as a special subset of the still life has mainly been used as a demonstration of artistic virtuosity. It found particular favour in the United States in the second half of the nineteenth century and lives on in a more modern guise in photorealist and hyperrealist painting. In the hands of Pop artists it served a critical-ironical purpose and shifted towards sculpture in works such as Jasper Johns’s Painted Bronze (Ale Cans) of 1960 (oil on bronze) and Warhol’s Brillo Boxes of 1964 (screenprint on wood). In the early 1970s “radical realists” such as Duane Hanson and John DeAndrea turned heads with their naturalistic human figures made from polyester resin and fibreglass. For a while, trompe l’œil seemed to fall somewhat into abeyance, until in the early 1990s there was a reawakening of interest in its techniques, aesthetic and philosophy. And although Kabakov was far from alone with his trompe l’œil constructs, he can be seen as one of the pioneers of the rediscovery of what has become a widely used strategy, where aesthetic confusion is born of heightened realism. Artists as diverse as Robert Gober, Peter Fischli and David Weiss, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Janet Cardiff, Guillaume Bijl, Christop Büchel, Maurizio Cattelan and Ron Mueck all have their own take in their own media – sculpture, installation, video, photography – on this tool, where the moment of bewilderment puts a strain on our perceptions and, in so doing, may deepen our appreciation of art and of the artistic image as a multi-layered tangle of multiple aspects of perception and knowledge.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss

Detail of Untitled (Tate) 1992–2000

Carved and painted polyurethane

Courtesy Eva Presenhuber/Tate © Peter Fischli and David Weiss

Mark Wallinger is another exponent of trompe l’œil. His State Britain 2006 was a memorable monument to Brian Haw’s peace camp in Parliament Square, which was largely removed by the police in May 2006. On a scale of 1:1, Wallinger’s installation was the outcome of months of meticulous reconstruction work based on photographs he himself had taken, more or less by chance, before the passing of the iconoclastic act. In effect he created a sculptural record of what would otherwise have survived only in documentary photographs and film footage. It would be fair to describe this artistic replica of a non-artistic installation, which had its first showing in the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain, as a political homage: an ephemeral peace protest that the State has felt the need to destroy some months previously was now – not only in the public eye once again, within the shortest possible space of time, but also ennobled by its new permanence.

As in the case of his painstaking reproduction of Haw’s peace camp, which was in effect transformed into a political still life or history painting, the heightened humanity of Wallinger’s sculpture Ecce Homo 1999, shown earlier in Trafalgar Square, had also highlighted the narrow aesthetic dividing line between art and reality. The use of all but identical materials for the reproduction of Haw’s posters and objects sets this trompe l’œil method apart from other modes of deceptive replication, as in Warhol’s Brillo Boxes or Fischli/Weiss’s coloured polyurethane sculptures. In the case of State Britain, Wallinger created a reproduction that was “authentically original” – to borrow a tautologous notion from the advertising industry – in order to induce a sense of critical doubt in the viewer, who can never be quite sure whether these are actual relics or a work of art that almost imperceptibly adjusts ordinary items (political or otherwise) by just one millimetre, and thus creates a whole new set of parameters.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Anne of Cleves 1999

Gelatin silver print

149.2 x 119.4 cm

Courtesy Gagosian Gallery © Hiroshi Sugimoto

Besides sculptors and installation artists, some contemporary artists working with photography have also joined the circle of optical illusionists. Notable instances are Hiroshi Sugimoto’s famous series of wax-figure portraits of the wives of Henry VIII, where the veristic medium of photography is used to bafflingly lifelike effect, and Thomas Demand’s way of making pictures based on photographs of three-dimensional models.

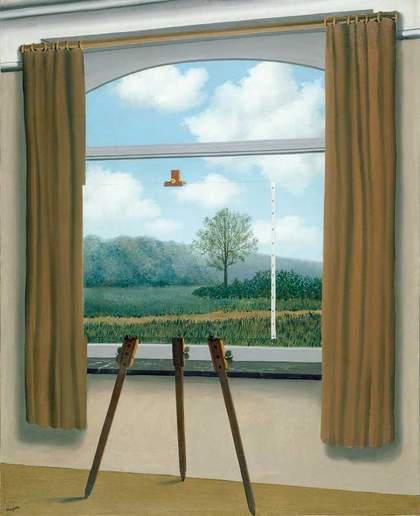

In summer 2003, for instance, anyone strolling through the frounds of the Venice Biennale and passing by the garden cafe in the centre might well have come across a poster-like photo-installation of a colourful woodland scene. Although this picture-wall was strikingly large (192 x 495 cm), it was perfectly possible to overlook it, because it was presented without any frame. From a distance one already had the impression that the image was of the trees in the immediate surroundings – in fact, of the very trees that it was obscuring. Games of this kind, toying with reality, are already familiar from the paintings of Magritte. One of the most famous, La Condition Humaine (1933), is a depiction of the view from a window, partly hidden by a painting on an easel. The painting, a landscape, fills in almost seamlessly the view of the real countryside outside the window – on the same scale, in the same colours and with the same perspective – so that picture and reality seem to have become one: an illusion that gives (visual) form to a long (art-) philosophical discussion.

René Magritte

La Condition Humaine 1933

Oil on canvas

100 x 81 x 1.6 cm

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

In Venice it was hard for the viewer to tell whether this was a decorative windbreak, an anonymous billboard or a work of art. In the end it was only the small label that indicated that it was a new work by Thomas Demand. Now the viewer felt obliged to go back and take a closer look, and suddenly all was revealed. The thousands upon thousands of leaves in the picture had in fact been made from paper, carefully positioned as foliage and only then photographed. Viewers found themselves contemplating a three-dimensional, superbly-lit paper world, captures on film as a photographic image, printed on a scale of 1:1 and mounted on a board – a large-format image behind plexiglas of a sculpture made from coloured paper and card, presented as a hoarding of sorts; a lengthy, technically complex process of reproduction that had ultimately returned the image to exactly the same spot where it had started.

While the title of the work (Clearing) is on one hand purely descriptive, at the same time it also has associations with the notion of clearing something up, which could in turn be relevant to this installation as a paradoxical visual trick. The foliage is copied in astounding detail and looks so “deceptively real” that one is hard put to see through the visual sleight of hand – a lesson in illusion and disillusion, in simulation and obfuscation, delighting and deceiving the eye in the spirit of a tradition that goes right back to the illusionistic wall paintings of classical Rome.

Demand’s installation was in direct confrontation with nature. His idea of pitting an image on the scale of 1:1 against real rees led to the creation of an extraordinarily detailed sculptural stage-set, made – by 30 people working for three months – from 280,000 separate pieces of coloured paper, flower wire and rolls of carpet in order to achieve the desired, entirely natural-looking effect. Only one among many of his works that engage with trompe l’œil, it not least provides an opportunity to re-examine the fundamental capacity for deception that is intrinsic to photography. For however much the technological nature of photography as a genre and a medium meant that it initially, as a matter of course, was used for the “faithful” depiction of reality, it seems that – as a fundamentally mimetic tool – in its early days it was barely used for the purposes of visual illusion. On one hand, its black-and-white images, usually considerably smaller than life size, were patently not suited to the creation of pictorial illusions. On the other, in the nineteenth century the general view was that photography had nothing to do with any deeper creative spiritual principle, or with art as such.

Demand had to make a major detour en route to Clearing. And it is only this doubly and trebly interrupted distance to reality that imbues the artistic image with its characteristic qualities. Above all, it is particularly the use of technical media that allows this picture to fulfil its ambition as a photographic image of a (man-made) image of a photographic image. As in antiquity, the element of deception promotes a self-reflective assessment of the medium and is, to put it rather grandly, beholden to the truth of the image – as it were, making free use of Max Leibermann’s maxim: “Nothing is less deceptive than appearances.”