A good deal of the art history being written today isn’t art history at all. Rather, it consists of exercises in anachronistic classification in which artists are assigned tags and lined up in groups according to ideological and stylistic genealogies. The rubric of Conceptualism,for example, becomes the catch-all basket for a disparate array of aesthetic practices, notably textual art, appropriated and manipulated photos, the hard core performance art, video, installation art, readymade sculpture and allied subgenres. When it comes to identifying the antithesis – if not nemesis – of Conceptualism for those who deem it the only true path for progressive postmodernists, the usual suspect is painting. It would appear equally obvious to such pro-pomos that painters have nothing much to do with Conceptualism, although licences to paint are issued to, among others, artists such as Art & Language, John Baldessari and Gerhard Richter, that one-man undoer of all dogmas.

Still, the art historical record seldom reflects many of the more intriguing anomalies buried with current customs of classification. Take the case of Per Kirkeby, and, for contrariness sake, begin at the beginning of this Danish artist’s long career with a group of works that are usually ignored, and a few pertinent facts that are habitually glossed over when his name comes up. The paintings, few in number, are square mixed-media works on masonite dating from 1968 and 1969. Kirkeby was just entering his thirties at the time, having abandoned the university study of natural history he began in 1957 to enter the Experimental Art School in Copenhagen in 1962, a year after it was opened as an alternative to the Royal Academy. Already behind him was intensive work as an academic and field geologist – as Lasse B. Antonsen writes in one of the best synoptic accounts of his early career, Kirkeby took part in two expeditions to Greenland in 1958 and 1962. Ahead of him at the Experimental School were life-altering encounters with recent and current vanguard art, notably that of the paintings of Wols, the drawings and poems of Henri Michaux, the music of John Cage, the multi-media events of Fluxus and the art and mentorship of Joseph Beuys (who Kirkeby first met when both showed up a day early for one of Beuys’s actions at the Royal Academy). In short, Kirkeby was a polymath in tune with his times, which is to say a well-educated man and an improviser all at once.

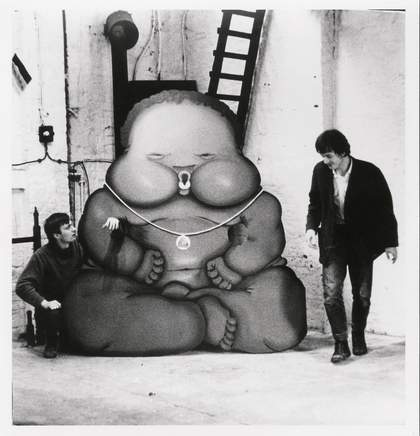

Per Kirkeby and Bjørn Nørgaard with Jörg Immendorff's Fotonegerchen, Aachen, Germany 1967

Courtesy Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

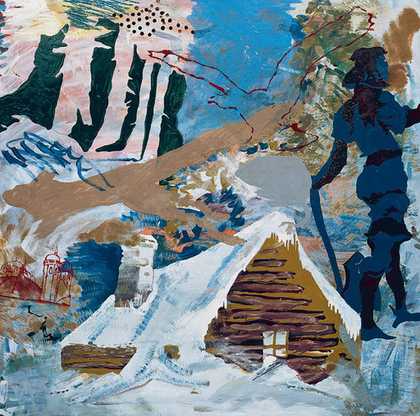

Unsurprisingly, his early masonite paintings are a vigorous aggregate of multiple aesthetic precedents, with lots of raw, youthful ingenuity and energy thrown in. Within their equilateral formats the unstable colours and gestures of informel – more specifically those of the Cobra movement with its foothold in Copenhagen – bump up against the bright hues and hard-contoured shapes of British and American Pop, while spectres of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Danish landscape painting grow in the cracks between the many-faceted modernism that prevails.

It is significant, given these artistic compass points, that the Pop element does not quote New York advertising, Hollywood movies or mainstream American comics, but instead lifts its motifs from Hergé’s Tintin books, and imports the exoticism for which the Belgian cartoonist was loved by adolescents throughout Europe and is now condemned by post-colonial critics everywhere. It is easy to see how the adventurer in Kirkeby, the young geologistturned- artist, would have been attracted to Hergé’s crisp depictions of faraway places and fantastic events – in particular the stories of Tintin’s excursion to the Himalayas, and the landing of a comet on a remote island. From vthese stories he borrowed the image of a Tibetan stupa (a Buddhist religious monument), a giant mushroom spurred to mutant proportions by the comet and other details. The end product is a kind of collage romanticism elaborated by brushy passages of pure painterly painting, loose silhouettes and a snappy, all-over agitation of the surface that recalls the early works of the Swedish polymath Öyvind Fahlström, of whom Kirkeby must have known, and graphic dreaminess of the American recluse Jess, about whom he could not have known.

Per Kirkeby

The Murder in Finnerup Barn 1967

Mixed media on masonite

122 x 122 cm

Courtesy Galerie Michael Wener, Berlin, Cologne and New York, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark. Donation Otto Bruuns Fund © Per Kirkeby

Why dwell on these paintings and their moment? In order to adjust our perspective sufficiently to encompass Kirkeby’s whimsy and the breadth of his knowledge about cutting-edge art of that febrile era. And why is that necessary now, on the occasion of his retrospective at Tate Modern? Because he has become a captive of categories in which he does not completely fit, as a consequence of the streamlining of history, and because even his defenders have stressed his links to northern European nature painting to the point that his particular reasons for painting nature, and his peculiar ways of denaturing painting, tend to get lost. Between the old-time religionists of 1980s Neo-Expressionism and the stern iconoclasm of Neo-Expressionism enemies, Kirkeby has too frequently been typecast when he has been given any prominent role in the story of post-war art. In that respect, the early Tintin paintings are a useful touchstone, as they hint at the wide range of his interests and activities. Yet, while full of seemingly incommensurable images and effects, they do not explain themselves. Already they display the strange mixture of alternating pictorial transparency and opacity and momentary flashes of pure poetry that henceforth distinguish his paintings.

Per Kirkeby

Nikopeja II 1996

Oil on canvas

200 x 200 cm

Courtesy Galerie Michael Werner, Berlin, Cologne and New York © Per Kirkeby

If northern light is to be taken as the hallmark of Scandinavian art, then Kirkeby is among the handful of Scandinavian artists who, although he himself rarely paints landscape as such, have captured that light in all hours of the day (such as those sudden changes in weather that can turn a radiant sky into a dense wall of clouds and back again). Presently, there seems to be little enthusiasm among people with advanced taste or ideas for such naturalism, even when translated into abstract terms as Kirkeby does. This, and the fact that he didn’t use painting to undertake a re-examination of history’s horrors as Anselm Kiefer, Jörg Immendorff, Richter and his German contemporaries did – being Danish spared him the daylight nightmares they suffered – leaves him odd man out of the group of painters that claimed the stage at the beginning the 1980s. Perhaps a ‘greening’ of art will change things and put him back in the mix thematically. In any event, he holds his own simply as a painter, and ultimately it is the freshness of his work in that medium upon which his reputation will primarily – and securely – rest.

The other foundation upon which Kirkeby’s reputation sits is sculpture, specifically monumental, architectonic sculptures. Some of these monuments are made of clay or cast in bronze and are no bigger than the palm of one’s hand. Others built of brick would be big enough to house a family were it not that they are either open to the elements or entirely sealed off like tombs. These constructions are symbolically and stylistically polyvalent and, as such, ambiguous if not deliberately mysterious. Quite a few are reminiscent of Romanesque sanctuaries, except that Kirkeby avoids the kitschiness of readymade ruins familiar to us from seventeenth-, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century follies. Others have a decided modern aspect as if they were incomplete Danish buildings, and a couple enter into indirect dialogue with Sol LeWitt’s cinder-block sculptures– on account of their masonry-based modularity and their allusions to monumental forms that come down to us from antiquity.

To speak of these as outdoor sculptures or monuments can be misleading on two counts. First, they commemorate nothing. Kirkeby is not a symbolist in that sense, much less a socially or ceremonially minded one. Second, they are not there just to be looked at, or at least not by a static spectator. Rather, the artist intends that they be walked around and, in some cases, through, so that one simultaneously experiences them visually and kinetically, effectively remaking them as a physical, spatial and mental gestalt from multiple viewpoints. To that extent they are closer to installation art than to sculpture as it is conventionally thought of, albeit a kind of installation art in which obdurate permanence is among the most powerful attributes. The other attribute is not contained in the material substance of the work itself, but expressed in its capacity to annex and frame its immediate environment. In most instances, nature is a primary component of what surrounds the sculptures, although such natural phenomena are already domesticated – no false wilderness mars Kirkeby’s settings with melodrama – and the parks where his monuments are located along with the ambient buildings always remind one of an immanent urban reality. For Kirkeby, nature and culture are never antagonists, but always collaborators. That is true of his art generally.

Per Kirkeby

Brett - Felsen 2000

Oil on canvas

220 x 200 cm

Courtesy Galerie Michael Werner, Berlin, Cologne and New York. Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark. Donation Jytte and Dennis Overing © Per Kirkeby

In an age when simple contraction was the starting point and heightened contradiction the end point of so much work, Kirkeby has focused if not on synthesis, then on balancing different media in a mutually enhancing tension. The results, which entail coming back to aspects of modern art that post-modernity thought had been left behind forever, but which actual re-engagement shows are still vital, are grounding. And in Kirkeby’s moody, thoughtful way, they are affirmative.